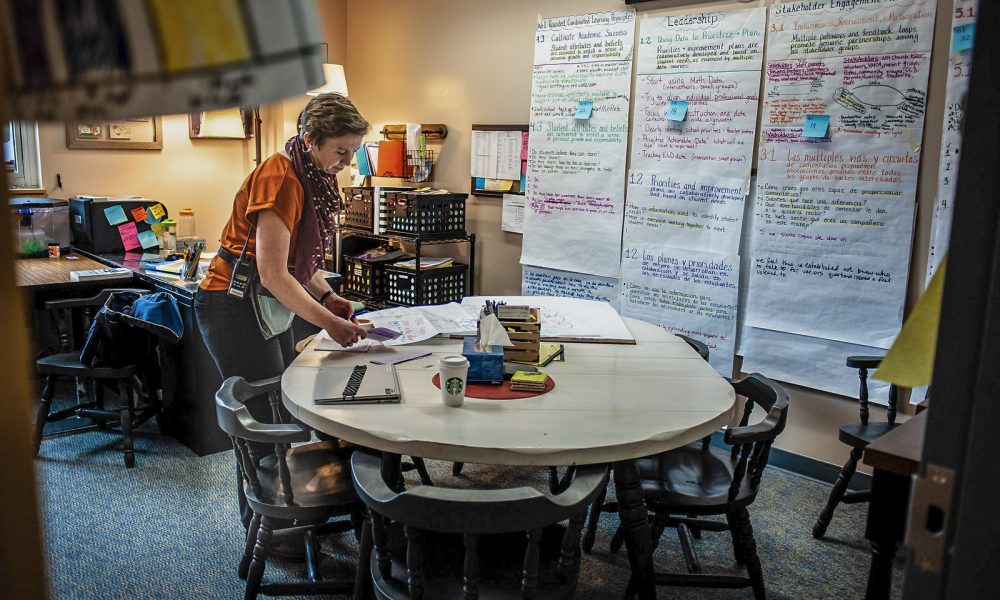

Hallman Elementary principal, Jessica Brenden photographed in her office Wednesday March 13, 2019. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

Jessica Brenden is always brainstorming.

The Hallman Elementary School principal’s office walls are covered in whiteboards and notepads, where she sketches out thoughts on how to help her students achieve more.

Early in the year, she calculated how much extra class time her 420 students would get if they extended the school day by 35 minutes. The verdict? It would be like adding an extra year of school to the six they now spend at Hallman.

Brenden doesn’t have the funding to do that, but it hasn’t stopped her from thinking about it. For her, the school is a calling, one she feels she shares with her staff.

“They understand that public school can be the great equalizer to kids,” she said.

Brenden came to Hallman in 2015 with a goal to bring stability to a school that had seen three principals in six years.

Nearly a decade ago, Hallman Elementary School was a guinea pig to experiment with how to turn around a struggling school. An influx of federal funds over three years helped more students pass state assessments and put teachers through intensive work on developing lesson plans and sharpening their skills in the classroom.

But it also caused some staff to leave, and gains were starting to slide when Brenden took over.

Situated in a neighborhood of rental houses and apartments just south of where Portland Road meets Interstate 5, Hallman serves about 420 students a year, about two-thirds Latino. The modern, two-story school was built in 2001 at the end of a cul-de-sac surrounded by trees. Its tiny parking lot and short bus lane attests to the expectation most students would walk to school from nearby homes.

About one quarter of its students met state reading standards last year. That performance ranks Hallman about in the middle of Salem-Keizer schools serving poor students.

But state data shows students at Hallman are learning.

Year over year, kids are gaining on test scores at a rate slightly faster than the state average. The percentage of students passing tests grows from third to fourth grade and again from fourth to fifth. By fifth grade, more than a third are on track in reading.

For Brenden and school staff, that’s a sign of success, given that the average student comes into kindergarten at the school knowing fewer letters, sounds and numbers than peers across Oregon.

“By the time they get to fifth grade, usually they’re only a year behind,” she said.

That wasn’t always the case.

In 2010, Hallman was among the lowest performing 5% of high-poverty Oregon schools, the only elementary school on that list.

The U.S. Department of Education that year began a grant program to fix struggling schools through sweeping changes, which could include closing the school and sending students to a higher-achieving school nearby, converting the school to a charter, or replacing the principal and a large number of teachers while revamping instruction.

At the time, about half of Hallman third graders were meeting state standards for reading. The state average was 83%. Worse, only 40% of Hallman’s fifth graders could pass the reading assessment.

“This pattern is troublesome … an increasing achievement gap in reading is evidenced through grades 4 and 5,” school officials wrote in their application for state money. “Students who may have achieved benchmark status in grade 3 are not maintaining a grade-level trajectory.”

Hallman students gather during the school’s morning assembly. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

Many students in the area were transitory, something that hasn’t changed much in the years since. Many came from farm working families who moved during the year, following work, or traveled long distances to visit family.

In the spring of 2010, about one in five students in the school had started at Hallman that year, and by year’s end, one in five of those who started the year at Hallman were gone. More than half of the school’s fifth graders had attended less than two years.

Hallman won a $3 million grant spread over three years. The school was one of just 12 in Oregon to receive the grant, and the only elementary school.

“We did it as a team of people who were interested in helping our school,” teacher Julie Cleave said. She’s now in her 16th year at Hallman and was part of a group of teachers that pursued the grant.

With the money in hand, Hallman teachers and staff revamped the school. Some changes, like a longer school day, were temporary because they could be done only as long as the grant money lasted.

Other changes were permanent. Knowing most students didn’t have access to good books at home, staff spent thousands on new books for classroom libraries. School leaders hired coaches to mentor teachers, invested in better technology for classrooms, held parent meetings and gave teachers extra pay for staying at the school.

With extra funds to pay teachers for extra hours and hire substitutes, teachers had time to plan lessons in-depth, track how individual students were performing and address gaps as they came up.

Cleave remembers it as a time she grew significantly as a teacher.

Normally, “you don’t have that luxury of really digging into your stuff,” she said.

Julie Cleave, reading specialist at Hallman Elementary School, helps students learn about length and measurement. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

The work showed results, at least initially. During the second year of the grant, about 60% of Hallman students met reading and math standards. Students also improved their scores more year-to-year.

It was also a turbulent time for the school.

Some teachers didn’t want to put in the extra hours and left. The school went through three principals before Brenden arrived in 2015.

Brenden said when she came to the school, many staff felt the progress from the grant was wearing off.

The teachers at Hallman had been through a grueling three years to remake the school. Those who had stuck it out were skilled teachers who genuinely wanted to be there, she said.

“The people who are here are the ones who really learned from the (grant),” she said.

But frequent changes in leadership hurt morale, staff turnover was high, and some of the new systems weren’t being monitored or maintained.

There was no school-wide process for helping kids behind on reading, for example. Each kid who was struggling got an individual plan, which created “chaos” for teachers and staff who were trying to juggle dozens of students, Brenden said.

She worked with school leaders to create a school-wide process to identify kids behind and use small groups to help them practice skills.

The team took the same approach for student behavior, working with teachers to talk about expectations in class and make it clear for all kids what’s expected at school. Kids who still struggle to stay calm or focused in class get pulled out for extra help, like a brief meditation or exercise break.

“It took all the frenzy out of the daily operations here. It just added calm,” Brenden said.

Around the U.S., results from such grants were mixed, said Shawna Moran, an education program specialist with the state Education Department. Some schools showed dramatic improvement in test scores or growth, only to slide back into struggling within a few years. Some showed sustained progress and others didn’t move much at all.

Moran said Hallman’s progress lasted beyond the grant money, which she believes helped the school improve.

“They were definitely installing systems that really targeted their students that had needs. It seems to me that those systems have definitely contributed to the growth,” Moran said.

Cleave agrees the grant was good for the school, and for the teachers who stayed. She said student performance dipped somewhat, particularly in the years between when the grant ended and when Brenden came on board.

“We spent a lot of money putting in professional development for teachers who left the next year,” she said.

This year, the average Hallman teacher has been in the district for about eight years, and teaching for nine, district data shows. Brenden said turnover has slowed to just one or two people per year out of a teaching staff of 21. Though she wasn’t at the school while the grant was being used, she feels one result was a stronger community of staff who know their work is going to be hard and show up anyway.

“Teachers overextend themselves here, but they don’t seem to burn out,” she said. Those who have stayed at the school share her drive to “be a game-changer for kids who have some setbacks.”

“We have people doing girl’s hair in the mornings because they come to school with uncombed hair,” she said.

Hallman remains a challenged school, but Brenden said the systems in place are strong and still evolving to keep up with student needs.

On a recent Thursday before school, teachers filed into the second-floor school library, a few bearing pies to celebrate National Pi Day. In a little less than an hour, they worked as a group to plan the next six weeks of classroom math instruction.

Kindergarten teachers took a table by the far windows, discussing where their students were struggling with place value. Teacher Bryndle Jarvis said her students have trouble thinking of the number 11 as one ten and one one, because it doesn’t follow the same pattern as numbers like 21 and 31.

“Teen number are just harder,” Jarvis said, to nods of agreement.

Kathy Stewart said she has the same problem teaching in Spanish, particularly for numbers between 11 and 15. They swapped ideas for getting the concept across. Jarvis said she calls the numbers the “tricky teens” because her students like to say, “You can’t trick us!”

As fourth grade teachers discussed how best to explain adding fractions, Brenden walked from group to group, listening in and offering input.

“There’s four meetings left to work on this year’s stuff!” she reminded the group as the session neared an end.

Jessica Brenden, Hallman Elementary principal, leads her students chanting an affirmation during the Morning Meeting Wednesday March 13, 2019. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

Brenden and the school’s leadership team work with teachers to track overall student progress on reading based on in-class assessments. At the start of the year, those tests showed third and fourth graders were struggling most, so those teachers got paid to stay an extra hour every month after school to do more planning. That effort picked up, so Hallman is now focusing on second graders, she said.

The goal of those sessions isn’t to have her dictating how classes are taught. It’s for teachers to spend time digging into what’s working and not so they can collectively teach in ways that are effective.

“If we’re not using the same strategies and techniques in the classroom, we’re not learning anything,” she said.

Students were beginning to file into Hallman as the teachers wrapped up their discussion. Brenden went straight to the gym, where she set aside data and standards and briefly transformed into a game show host.

Hallman students start the day with a short assembly to hear announcements and work out some energy – in this case, by competing to see which kid can shake dozens of ping-pong balls out of a box strapped around their waist by jumping up and down.

Brenden took the winner’s hand and thrust it in the air as if the student were emerging from a wrestling ring victorious, then kept cheering until every student had finished

Then, it was time for some deep breaths and affirmations.

“I deserve an education!” Brenden yelled into a microphone. Four hundred students yelled the sentence back at her.

Correction, April 18, 9:45 a.m.: This article incorrectly listed the average experience of Hallman teachers for this school year. The earlier, lower number was an average for the past six years.

This is part three of a five-part series examining the Salem-Keizer School District’s most challenged elementary schools.

Part 1: Salem schools struggle with shifting politics, challenging demographics, lagging students

Part 2: Four Corners educators fight the odds to boost student literacy

Part 3: Hallman Elementary turns federal money into student success

Part 4: With teachers staying put, Highland students make progress

If you have questions or comments, please email them to [email protected].

Reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Follow Salem Reporter on FACEBOOK and on TWITTER.

YOUR SUBSCRIPTION WOULD HELP — Salem Reporter relies almost exclusively on reader subscriptions to fund its operations. For $10 a month, you hire our entire news team to work for you all month digging out the news of Salem and state government. You get breaking news alerts, emailed newsletters and around-the-clock access to our stories. We depend on subscribers to pay for in-depth, accurate news. Help us grow and get better with your subscription. Sign up HERE.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.