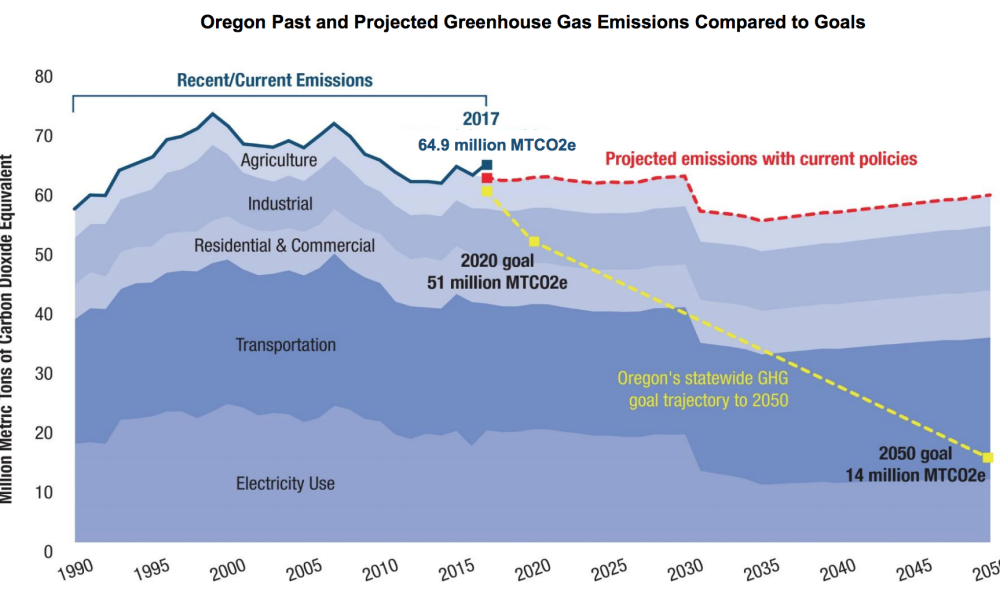

A graph from a presentation Gov. Kate Brown’s staff made to the legislative committee overseeing cap and trade shows how the policy is projected to impact pollution levels.

In two generations, Oregonians might drive along freeways and not see a single industrial smokestack. They might instead see solar panels or wind turbines. And they might see them from an electric vehicle.

That’s the goal of Oregon politicians trying to pass legislation to charge companies for polluting. The hope is to decrease carbon emissions in the state by nearly 80 over the next 30 years. Oregon producers now emit an estimated 65 million metric tons of greenhouse gasses per year.

The “cap and trade” policy would regulate oil companies, utilities and industrial emitters by essentially taxing those that don’t steadily decrease their pollution overtime. Similar efforts have failed year after year.

As momentum builds ahead of the 2019 Legislature, the fight has turned to which industries should be sheltered from new state taxes and how much protection they really need.

Climate scientists continue to warn about the implications of a hotter planet with more extreme weather patterns. A 2018 report from U.S. Global Change Research Program found the climate — forests, streams and a diversification of wildlife — is the foundation to how Oregonians make a living and recreate.

“Climate change is projected to continue to have adverse impacts on the regional environment, with implications for the values, identity, heritage, cultures, and quality of life of the region’s diverse population,” the report said.

That’s why those backing cap and trade say society has waited too long to change ways of living, and further delay would be at the expense of future generations.

Others say it’s a complicated and expensive undertaking that will hurt everyday Oregonians now, especially in rural areas.

Lawmakers have built concessions into past and proposed legislation to soften the hit on polluters and keep from driving them from the state. But there is fear that too much generosity could render the concept toothless.

“The more free allowances you give, the more you ease people in, then we start to look at getting where we need to go in the next 30 years rather than the next decade,” said Meredith Connolly, Oregon director for Climate Solutions. “It does matter that we are really watchdogging how many allowances really need to be given for free, and we want to make sure legislators are evaluating that need overtime.”

Climate Solutions is a nonprofit that advocates for climate policy reform.

Past efforts to impose carbon restrictions limited annual emissions at any one site to 25,000 metric tons per year. That cap — 25,000 tons — is the equivalent of burning 136 railcars full of coal per year, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Companies could exceed that limit, but would have to pay for the privilege by buying “allowances” through a state auction. The allowances would essentially serve as costly permission slips to break the state’s limits. In 2021, when the proposed policy would go into effect, the projected base cost to exceed the limit would be $16 per ton.

But the proposed legislation is building in a system for the state to give such allowances at no cost, especially to industries vulnerable to the change. Proponents want to avoid having companies move out of state and continue their polluting ways elsewhere, which helps Oregon but not the overall climate.

Proposal materials introduced last week by Governor’s office showed 30 companies could qualify for free allowances.

Gov. Kate Brown also is now proposing to exempt electric utilities from the emission limits for a decade and wants to mitigate the cost of the allowances for small businesses.

Those pushing the environmental reforms say they will spur innovation and investment in cleaner energy production.

“I think we pay for the cost of carbon pollution anyway, and we just don’t see it on a price tag,” said Nancy Hamilton, co-director of Oregon Business for Climate. “And those costs are just going to get higher and higher. It’s a false proposition that it’s going to cost to do cap and trade.”

Hamilton said her organization, which supports carbon emission limits, doesn’t want a policy that is costly to citizens or drives industry from the state.

Shelly Boshart Davis, a Republican who takes office next month as a state representative, has been appointed to the joint committee that will shape the policy. She said there is a slight chance she would support the policy with enough concessions, but recent changes, like Oregon’s clean fuels standard, need more time to show an impact.

“Let’s allow those to work before putting in an extremely complex and costly program on top of other programs already in effect,” she said.

Taxing oil companies trucking gas through the state is expected to be passed on to the consumer, with some projections showing a 10- to 16-cent increase per gallon on gasoline. Boshart Davis said that would cost her trucking business hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

“Gas in Oregon went down 22 cents per gallon in the past three weeks,” Hamilton said of the common argument from the opposition. There is a lot of volatility in what we pay at the gas pump, and it doesn’t seem to have put everyone out of business.”

Whatever Oregon does, it’s not projected to by itself improve the global climate. But supporters say it’s the most meaningful change the state can make. Proponents say Oregon can be a pioneer on the issue. Hamilton said because Oregonians care deeply about their rich natural resources, they may be more inclined to protect them.

“The state of Oregon has taken the lead on some really important legislative actions to make sure our natural resources-based state is left intact,” she said. “This is just the next thing we need to do.”

Shaun Jillions, executive director of manufacturing lobby group Oregon Manufacturers and Commerce, said he agrees emission levels are a problem, but doesn’t understand why Oregon should act.

“Being the first to model something for the rest of the country isn’t always the best plan,” he said.

Jillions said if the price of electricity and natural gas goes up, manufacturers would be hit.

“By its very nature, a cap and trade system is designed to make energy less affordable unless it’s 100 percent renewable,” he said.

Reporter Aubrey Wieber: [email protected] or 503-575-1251. Wieber is a reporter for Salem Reporter who works for the Oregon Capital Bureau, a collaboration of EO Media Group, the Pamplin Media Group, and Salem Reporter.