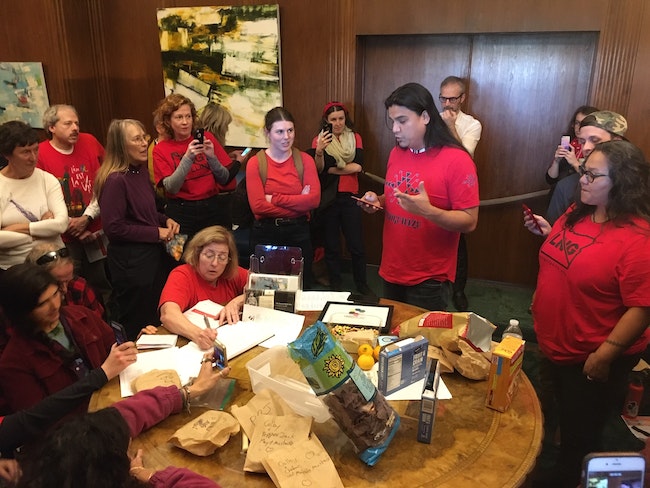

Opponents to the Jordan Cove pipeline held a sit-in at Gov. Kate Brown’s office Thursday. (Sam Stites/Oregon Capital Bureau)

Opponents to the Jordan Cove pipeline held a sit-in at Gov. Kate Brown’s office Thursday. (Sam Stites/Oregon Capital Bureau)

SALEM — Protesters upset over a gas pipeline slated to cut across southern Oregon filled Gov. Kate Brown’s ceremonial office Thursday, vowing to stay until the governor announced her own opposition to the pipeline.

The protest began Thursday morning with more than 200 people on the Capitol steps. About half of them moved into the rotunda by midday. Protesters cheered and gave speeches.

“We’re not happy,” said Thomas Joseph, a member of the Hupa Tribe of the Lower Klamath Basin. “It’s something she clearly knows and understands is bad for Oregon and is bad for climate change.”

The target of their action is a proposed liquefied natural gas, or LNG, facility in Coos Bay called Jordan Cove. The project is facing a federal decision to proceed, and includes a plan to run a gas pipeline across 200 miles of Oregon landscape, from the border town of Malin east of Klamath Falls to Coos Bay.

Proponents say the project would be an economic boon for Coos County while environmentalists say the risks to Oregon’s environment are significant. The voice of the environmentalists rang in the governor’s office Thursday.

“She’s done what she’s continued to do — not answer the question and divert,” Joseph said. “The best possible outcome is that Gov. Brown takes a stand, denies the project and makes sure her agencies enforce her decision to stand up for the citizens of Oregon.”

[ Help build Salem Reporter and local news – SUBSCRIBE ]

According to Grace Werner of the climate group Southern Oregon Rising Tide, the idea to move the protest into the governor’s office was a spur-of-the-moment action.

“The governor has gotten really good at being on the fence with these issues,” Werner said. “There’s so much on the line for our communities. It’s hard to hear her say she wants our support when she’s the one with the power, and we need her to have our backs right now.”

About ten state troopers stood watch as about 100 protesters, many from southern Oregon, and wearing matching T-shirts saying “No LNG” inside a map of Oregon with a slash through it, sat in the governor’s ceremonial office lobby or spilled into the hallway.

“We really don’t have much comment,” said Capt. Tim Fox of the Oregon State Police. “My understanding is they haven’t broken any laws, and so building administration would need to ask them to leave.”

Legislative administrators, responsible for managing the Capitol, must decide if they want to declare the protesters to be trespassing.

Brown, while traveling to Eugene on state business, talked to the protesters by phone.

“I’ve been very up front with Oregonians on all sides of this issue that there needs to be a process that is fair and that everyone has the opportunity to be heard,” Brown told them. “I’m overseeing that process to make sure statutes are followed and Oregon’s regulatory process is complied with.”

Joseph asked for the governor to take a more decisive stance on Jordan Cove.

“We don’t think it’s a hard ask,” said Joseph.

Before ending the call, Brown asked them to keep up the good work and stand with her on opposing the Trump administration’s moves to roll back environmental protections.

“Spoken like a true politician,” one protester remarked afterward.

The fight over the pipeline has spanned more than a decade and has drawn highly vocal opposition from impacted landowners and environmentalists.

The latest development came last week when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission released the Final Environmental Impact Statement for the pipeline project, the last major document that will be published before FERC makes its final decision on the project. That is expected early next year.

“The Jordan Cove LNG facility, pipeline, and tankers pose big risks to me, my family, and the lives and property of my friends and thousands of local residents,” said Mike Graybill in a statement. He is a Coos County resident and former employee of the Oregon Department of State Lands. “I am taking action today to urge Governor Kate Brown to step up and take a position of opposition to this project. Oregon could and should invest in a future for Coos Bay that does not threaten so many people’s lives and negatively impact existing businesses and residents.”

A spokesman wouldn’t say whether Brown has a position on Jordan Cove.

“Gov. Brown expects state agencies to follow all laws and regulations to the letter when considering how any proposed project affects Oregon’s clean air and water,” spokesman Charles Boyle wrote in an email. “She has also taken measures to ensure the public’s input is taken into account during the processes.”

Boyle said Brown has met with the No LNG Coalition a number of times, including last June after a meeting of the State Land Board.

Canadian pipeline company Pembina claims its project could create 6,000 construction jobs and 8,500 “spin-off” jobs in industries like health care.

At 5.3%, Coos County’s unemployment rate is higher than the state average of 4.1%. The area has been hard hit by the steady decline of the timber industry over the past few decades.

Protesters say they fear the possibility that private land could be taken by eminent domain for the route of the pipeline.

“My husband and I have lived on our ranch for the past 29 years working extremely hard to create and live our dream,” said Sandy Lyons, a rancher in Days Creek. “For 15 of those years, we have been fighting the proposed gas pipeline which a fossil fuel corporation has chosen our land to cross and seize it from us by eminent domain.”

Conflicts between business and environmental interests tend to highlight Oregon’s political fault lines as well.

Environmentalists crowded the Capitol in June after Senate Republicans left the state to protest pending climate legislation. Their disappearance led to a stalemate where no votes could be taken.

After Senate President Peter Courtney, D-Salem, said that the legislation was dead, Brown jetted out of her office and appeared outside the Capitol to charge Republicans with being “against democracy.” She asked protesters then whether they had the “passion” and “persistence” to continue fighting for the legislation.

In 2012, state police arrested six people at the Capitol protesting a plan to log the Elliott State Forest, according to media reports at the time.

The six were arrested for criminal trespass, disorderly conduct and criminal mischief after dozens occupied the first floor of the Capitol, spending hours chained to each other to block the offices of the secretary of state and the state treasurer.

On Thursday, one of the protesters was Bill Bradbury, secretary of state from 1999 to 2009.

Bradbury, a resident of Bandon in Coos County, said he was “very, very proud” that the governor phoned in to talk to the protesters, but wished she took a more assertive position on Jordan Cove.

As the afternoon wore on, protesters continued to peacefully mingle over trail mix, gluten-free peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and delivery pizza in the lobby. Two state troopers stood calmly by the door to the governor’s office.

“We’re going to be here until Kate Brown makes a decision,” said Joseph.