About half of local openings for high-demand jobs pay lower wages (Graphic by Pamela Ferrara)

About half of local openings for high-demand jobs pay lower wages (Graphic by Pamela Ferrara)

In April of 2020, the Salem area unemployment rate climbed in one month’s time from 3.9 percent to 11.3 percent, due to business shutdowns to control the pandemic. The high unemployment rate put a glaring spotlight on this fact: the labor market has a lot of low-wage jobs.

Most of the thousands of workers laid off in the early months were low-wage workers in the leisure and hospitality industry, and in those low-paid occupations in other industries having extensive public contact. When these workers went back to work, they were exposed daily to Covid. Low-paid workers bore the brunt of the pandemic economy.

These workers were deemed “essential,” that is, necessary to keeping daily life going for the rest of the population. These workers, nearly all in the service sector of the economy, included grocery checkers, gasoline station attendants, retail clerks, day care workers, and nursing assistants.

Do policy makers and society in general have a responsibility to the essential workers who kept the economy going under the most trying circumstances? If they are so essential, why do they earn so little? What if anything should be done about it?

Let’s provide some information that might help answer these questions.

First, let’s look at the scope of the issue – how many low-wage jobs are there in the Salem area?

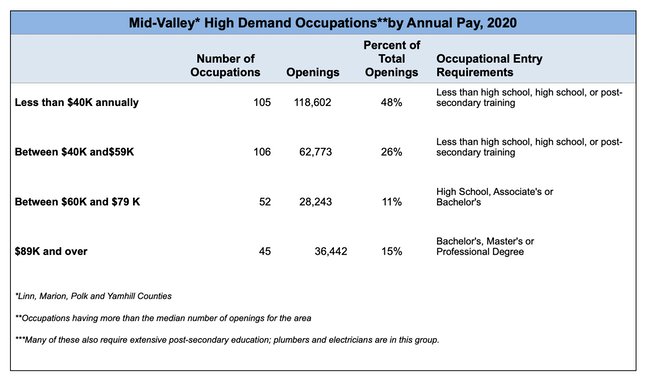

Oregon Employment Department economists provide a number of ways to answer this question. We’ll look at one of them, the occupational projections, and analyze high demand occupations and their characteristics – in particular, total job openings, annual salary, and occupational entry requirements, for the year 2020, the baseline year of the projections (see table above).

Seventy-four percent of the 181,375 total job openings in 211 high-demand occupations paid $59,000 a year or less. Most required less than high school, high school, or post-secondary training to enter. Occupations in the lower pay range included customer service representatives, bank tellers, data entry workers, and retail salespersons. Occupations in the higher range included medical assistants, pharmacy techs, firefighters and auto mechanics.

Twenty-six percent of the openings in 97 high-demand occupations paid $60,000 and above. A small number of these required high school to enter, but in addition, extensive training – plumbers and electricians are in this group. Most occupations in this pay range required an associate’s degree, a bachelor’s degree, a master’s, or a professional degree to enter. These occupations included lawyers, pharmacists, nurses, and human resource managers.

The proliferation of low-wage jobs isn’t unique to our area, or Oregon. This situation is common across all 50 states.

Why are there so many low-wage jobs? Decades of public policy decisions have produced a shift from work in goods-producing industries such as manufacturing, to service industry work. In turn, the labor market has become polarized, with a lot of low-paying jobs in both types of industries, some good paying ones requiring skills and education to enter, and not much in between.

What’s to be done? The occupational analysis above proves that education and training pay, and job training has long been the stock-in-trade of U.S. workforce programs. But even if it were possible to give all low-wage workers the education and training to enter high-wage jobs, where would they work? There aren’t enough good jobs to go around.

Researchers have looked at how workers move from low-wage jobs to higher-wage jobs. A classic study was done in 2006 (Moving Up or Moving On – Who Advances in the Low-Wage Labor Market). Using Census data, researchers found that low-wage workers rarely moved into higher wage jobs. When they did, workers who changed employers did better in terms of successful career outcomes, including pay, than those who moved up within the same company. The researchers concluded that there were employers who paid well, and those that didn’t, and that there needed to be more research into why that was the case.

Some of this moving around is going on now. Oregon Office of Economic Analysis economist Josh Lehner in a recent blog post reported an increase in the number of Oregon workers quitting jobs to take other jobs. The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, in addition, says the “quits rate” which is the number of people quitting jobs in a month as a percent of total employment, has increased in the western states from 2.4%to 3.2% from March of 2021 to March of 2022.

In a similar vein, ZipRecruiter, an online job-posting site, reports that in its monthly job seeker survey, more than half of employees think their current employer would offer more pay to keep them from quitting to take another job. The percentage of employees reporting this has increased steadily over the last few months. ZipRecruiter calls this “job seeker bargaining power.”

Whether or not the unusually tight labor market will be the impetus to increase workers’ bargaining power remains to be seen. In addition, if worker efforts to raise pay were to succeed, there’s a large body of research that describes what could happen as a result – increased automation and the use of robotics. One such study reported that the highest potential for future automation is in low-wage work in the service sector of the economy.

One effort to help the low-wage workforce focuses on assisting employers to better understand how employees view their jobs. A number of organizations are developing assessment tools to do this, in the hope that businesses will buy in, improve their workplaces, attract and retain workers more easily, and in turn, improve low-wage jobs.

But, if worker bargaining power fails to materialize, and employers adopt a “business as usual” stance, what’s left?

Public policy efforts to improve low-wage work are already law in Oregon and include Oregon’s minimum wage, more generous than the federal minimum and indexed to inflation, and mandated sick leave legislation, which covers most workers. These help some.

Some public policy “big guns”, if enacted, could have a substantial impact on low-wage workers’ incomes. These include a guaranteed minimum income, expansion of the earned income tax credit, and lowering the rate of Social Security payroll taxation on lower-wage workers. They are unlikely to get far in this era of extremely polarized politics.

Although so many low-wage workers made all our lives easier during the pandemic, it doesn’t seem likely that they’ll be rewarded financially any time soon.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected].

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!