SALEM — Many political observers around Oregon were surprised late last October when the most prominent third-party candidate for governor dropped out of the race and endorsed Gov. Kate Brown for re-election.

Patrick Starnes, nominee of the Independent Party of Oregon, said he decided to back Brown because he believed they shared common cause on perhaps the biggest policy issue of his campaign: campaign finance reform.

“We’re going to get this done,” Brown vowed at the time. “No question in my mind.”

Brown’s pledge is being put to the test in this legislative session. Lawmakers from both parties have proposed wide-ranging reforms that could transform the way election campaigns are conducted in Oregon.

There are more than a few obstacles to overcome along the way, though. The most significant might be the state Constitution itself.

In Oregon, campaign finance reform requires more than changing state law. That’s because of legal precedent set by the Oregon Supreme Court in 1997, when justices struck down limits on campaign contributions as violating Oregon’s constitutional right to free speech.

A trio of Democratic state representatives has proposed a constitutional amendment that would allow state and local governments to regulate campaign spending by limiting contributions to political campaigns and mandating that advertisements and campaign materials name who paid for them.

“I think most of us would agree that Oregon has been a leader when it comes to elections, whether it’s vote-by-mail or whether it’s ‘motor voter,’ but the one place that we have not led is in the area of campaign finance reform,” said state Rep. Dan Rayfield, D-Corvallis, one of the sponsors of House Joint Resolution 13, at a committee hearing last week. “I think most of us in this room would agree that the level of money being spent on our campaigns is much too high.”

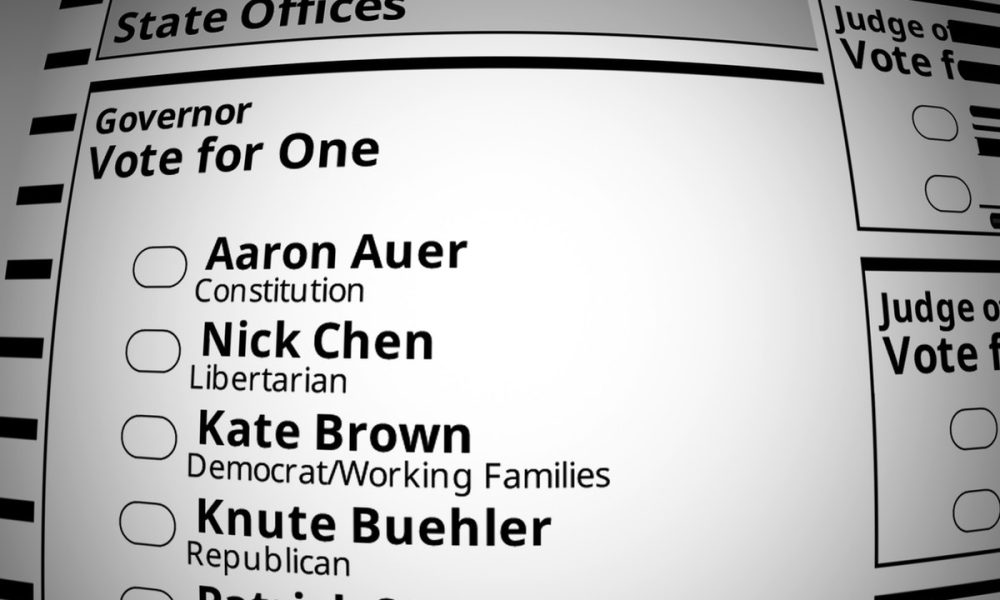

Last year’s gubernatorial race smashed records in Oregon for the amount of money that Brown and Republican nominee Knute Buehler raised and spent. Buehler received more than $19 million, while Brown raked in more than $20 million, according to financial disclosures filed with the secretary of state’s office in 2017 and 2018.

The amount of campaign money it takes to compete in Oregon has surged over the past decade. In 2009 and 2010, Democrat John Kitzhaber raised about $7.5 million in his successful campaign for governor.

In the Senate, Beaverton Democrat Mark Hass and Bend Republican Tim Knopp have proposed Senate Joint Resolution 18, a similar constitutional amendment to what Rayfield and Reps. Alissa Keny-Guyer, D-Portland, and Pam Marsh, D-Ashland, have put forward in the House.

“What we have today is an electorate who is becoming increasingly agitated and uncomfortable with where our elections are headed,” Knopp said Wednesday. “They have become much more divisive and negative, and the money seems to be less transparent than it used to be. And, of course, there used to be less of it.”

The main difference between the House and Senate proposals is that the former would allow cities and counties to set their own rules on campaign finance reform, while the latter would reserve that right to the Legislature or voters.

Both resolutions received a committee hearing last week. The Senate measure is expected to receive another public hearing before the Senate Campaign Finance Committee this Wednesday.

Rayfield and Keny-Guyer have proposed other bills as well, including House Bill 2716 and House Bill 2983, which were also heard last week.

HB 2716 would require any ad or campaign literature to identify who paid for it. An amendment offered by Sen. Jeff Golden, D-Ashland, would require that if literature is financed by an independent committee separate from the candidate, they include a disclaimer stating they are “produced and paid for without the knowledge, consent or cooperation” of any candidate for that office.

HB 2983 would require tax-exempt nonprofit groups that spend $50,000 or more on a legislative race to disclose the name of any donor who contributes at least $50,000, while nonprofits that spend $250,000 or more on a statewide race would have to disclose the name of any donor who gives them at least $250,000.

The proposals heard last week before an unusual joint meeting of the House Rules Committee and the Senate Campaign Finance Committee, are not the only election reforms legislators are studying.

Under Senate Bill 861, which the Senate Rules Committee considered last week, ballot return envelopes would no longer require postage. The state would cover the cost of mailing back ballots, which could top $3 million over a two-year period, legislators heard.

Brown testified in favor of SB 861. The bill had been supported by Dennis Richardson, Oregon’s secretary of state, who died last month.

The committee also heard testimony last week on Senate Bill 761, which would require that any person signing a single-signature petition sheet — commonly known as “e-sheets,” because they are designed to be distributed electronically — personally print it out rather than having it printed for them.

The American Civil Liberties Union’s Oregon chapter, which supports SB 761, argues that mass distribution of e-sheets is “a serious run-around of our current rules around signature gathering.” Opponents, including the secretary of state’s office, say that the requirement would be difficult to enforce and unnecessarily makes it harder for citizens to petition.

The Senate Campaign Finance Committee will also hear Senate Bill 1014, which would provide public financing to match some “small donor” campaign contributions, on Wednesday. Those public matching dollars would only be available to legislative candidates.

Not every campaign finance reform proponent is happy with what lawmakers have put on the table. Attorney Dan Meek argued that the proposals heard last week don’t go far enough, and he criticized constitutional amendment language that would not grandfather in campaign finance laws adopted before the 2020 election — such as local measures, in Multnomah County in 2016 and Portland in 2018, with which he was involved.

Multnomah County’s campaign contribution limits were declared unconstitutional last year by a circuit court judge, citing the 1997 Supreme Court ruling. The county has appealed to the state Supreme Court.

Another attorney who backed Portland’s campaign finance efforts last year said he thinks now is the time for the Legislature to act.

“There is tremendous momentum right now in this session,” Jason Kafoury said Wednesday. “If we can’t get it done in this session, then whenever are we going to get this done?”

Reporter Mark Miller: [email protected]. Miller works for the Oregon Capital Bureau, a collaboration of EO Media Group, Pamplin Media Group, and Salem Reporter.

Follow Salem Reporter on FACEBOOK and on TWITTER.

SUBSCRIBE TO SALEM REPORTER — For $10 a month, you hire our entire news team to work for you all month digging out the news of Salem and state government. You get breaking news alerts, emailed newsletters and around-the-clock access to our stories. We depend on subscribers to pay for in-depth, accurate news. Help us grow and get better with your subscription. Sign up HERE.