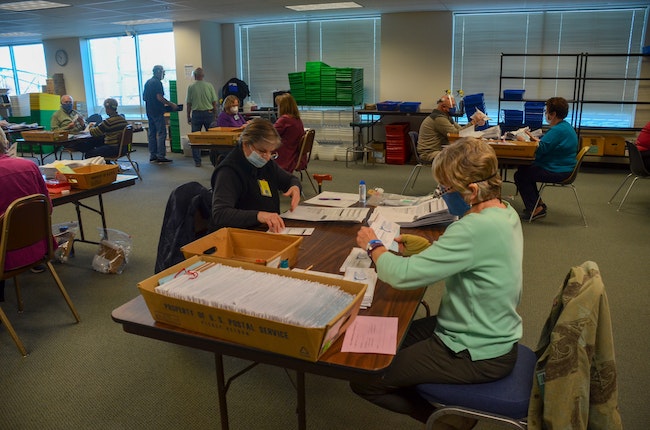

Election workers remove ballots from envelopes to prepare for scanning at the Marion County elections office on Oct. 27, 2020 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Election workers remove ballots from envelopes to prepare for scanning at the Marion County elections office on Oct. 27, 2020 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

With one week to go until the Nov. 3 election, Marion County’s election office is humming.

For weeks, clerks and election workers have been building up for what they expect may be the highest turnout election in Oregon history. Nearly half of the county’s 214,000 registered voters have already returned their ballots.

Polk County’s turnout is just over 50% as of Oct. 28, unusually high for one week before an election. The county has about 60,000 registered voters.

“We’re kind of excited at the fact that it seems like a lot of people did get out early,” said Cole Steckley, Polk County’s chief elections clerk.

In Oregon, votes can’t be counted until Election Day, but workers can sort, scan and prepare them, making for a quicker tally when the time comes. That process began in Marion and Polk counties Oct. 27 – the first day by law election workers can open envelopes and process the ballots inside.

The election this year is bringing extraordinary attention to the vote-counting process. President Donald Trump now regularly declares he expects fraud through mail-in ballots, a claim with no evidence. Still, elections officials across the country are working to assure voters the system is safe, legally-submitted ballots will get counted, and chances for fraud are slim.

Oregon election officials have 20 years of experience with vote by mail. The process is similar in each county, where the county clerk is responsible for conducting the election.

In Marion County, Clerk Bill Burgess walked through the steps each ballot goes through before any votes are announced next week.

Envelopes containing the ballots received already have been scanned, sorted by precinct and had signatures verified. In Marion County, a machine first checks the envelope signature against the one on file. It’s set to only accept clear matches, Burgess said – about half the ballots that come through.

Remaining ballots are checked by election workers manually, the same process used in Polk County and other smaller counties without sorting machines.

Before they head to the tables spread across the elections office, they’re run through a machine one more time to slice the bottom.

The office at the Marion County Courthouse is lined with tables, each with at least two election workers of different parties who process ballots together.

No black or blue pens are allowed at tables where ballots are being processed to prevent any stray marks from being added.

Election work, particularly ballot processing, is done in pairs or groups to guard against error and fraud. The process is open to observers, though the number who can be in the room at one time has been reduced due to Covid.

“You may have to wait a while until we have a seat for you,” said Burgess.

Election observer Ann Moore signs a declaration after witnessing Marion County’s public test of the vote tallying machine on Oct. 27, 2020 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Election observer Ann Moore signs a declaration after witnessing Marion County’s public test of the vote tallying machine on Oct. 27, 2020 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Still, anyone can show up at the Marion County Clerk’s Office and sit in a chair watching ballots be processed, though those seeking to represent a political party must get cleared through the county party office. Another room is open for observers to watch remotely via camera.

Ann Moore was one of several observers on Oct. 27, taking notes from the corner of the room.

Moore is with the local Democratic Party and said she cares about the election process, but doesn’t have a personality suited to knock on doors or cold call people. For several years, she’s chosen to observe instead.

“I want to be helpful,” she said.

Workers get trays of opened envelopes and extract the ballots. One removes the secrecy sleeve, then the ballot inside, and slides it across the table to the second worker. That worker unfolds the ballot and checks that the precinct listed on it is correct before putting it in a pile for further sorting.

Though there’s no way to tie an individual ballot back to the voter who submitted it once it’s out of the envelope, signed voter envelopes are kept on file for two years, Burgess said.

Whether a registered voter cast a ballot in a particular election is public record, Burgess said. People are often surprised to learn that, but he said it’s an important security feature.

If someone were to get around the other safeguards to prevent voting under someone else’s name, that public record provides a tool for a voter to come forward and challenge the result cast in their name.

“To me, that’s important. That holds us accountable,” he said.

Burgess is on the ballot this year, seeking re-election as county clerk against challenger Danielle Gonzalez, a longtime county economic development worker.

His role is to oversee the office, so he almost never handles ballots personally, he said. Like any other election worker, he’s never alone with ballots – having many eyes in the room at all times is a key part of election security.

And Burgess said he would never oversee a step in the vote counting process that’s a direct conflict of interest, like determining a voter’s intent for a confusingly-marked ballot in his race.

Once removed from envelopes and unfolded, ballots go to a new table, where a duo of workers inspect them.

Those workers decide if a ballot can be read by machine or must be manually read to determine a voter’s intent. Most ballots go through the machine with no issue – they’re filled out in black or blue ink and don’t have stray notes in the margins.

But anything a machine might struggle with goes for manual review – like ballots filled out in pencil, where the computer might miss a light mark.

Occasionally, workers set aside a ballot to be duplicated if it’s too stained, dog-eared or otherwise damaged to be run through a scanner.

Ballots then head to the counting room, a secured room at the back of the elections office which has security cameras at all times and no Internet or county network connection. It’s built to ensure vote counting is secure and ballots can’t be tampered with.

Each ballot is scanned, and copies of both the scans and the physical ballots are kept in case of a recount. The scanned ballot images are stored but won’t be tallied until election night.

On Oct. 27, Dan Brummer, elections support specialist, ran a test of the county’s vote counting machine to ensure it was working as intended. The process must be observed by at least two witnesses.

He scanned 32 test ballots he’d filled out to ensure the machines were recording votes as intended or otherwise flagging issues needing human review correctly.

Brummer also demonstrated how election workers resolve issues where a voter’s intent might be different than what the computer records.

On one sample ballot, he’d written a large X through the “Yes” box on Measure 109, which would legalize psilocybin therapy in Oregon. The X was so large, a fraction of one line crossed into the box for a “No” vote, and the computer had highlighted the mark as needing manual review before the scanned ballot could be processed.

Such issues are reviewed by two election workers from different political parties.

Their goal is to determine what the voter intended by the marks on the ballot, whether they’re a too-large X or a note in the margin. They’re aided by detailed state manuals clarifying how to resolve common stray ballot marks.

If left to the computer, Brummer’s ballot would be counted as an “overvote,” meaning someone voted for more than one choice in the same race, and neither vote would be counted.

“Between the two of us, we would determine that’s not what the voter’s intent was,” he said. Instead, the manual review would correctly determine the voter got a little too enthusiastic checking off one box. They would record the vote as intended, a “Yes.”

Any changes are logged in the system with the user and time so they can be easily reviewed for accountability. If the two workers can’t agree on the voter’s intent, another pair of workers is called over to help.

Election workers are also mailing letters to voters whose ballots won’t be counted because of a signature mismatch or unsigned envelope. So far, about 800 Marion County voters have been notified of signature mismatch issues, and about 100 didn’t sign their ballot envelopes, Burgess said.

In Polk County, 187 ballots have had a signature challenge, and 40 were unsigned, Steckley said. Another 73 so far have been flagged for other reasons, like someone from the same household signing the wrong ballot envelope.

Those issues are easy to correct by returning the form the elections office mails to voters, but many never take the step. Burgess said he hopes greater public interest in this year’s election will allow the county to fix more signature issues. Voters have until 14 days after Election Day to fix a signature issue, and their ballot will still be counted once the issue is resolved.

SALEM BALLOT BOX LOCATIONS

NOTE: Do not mail your ballot at this point. U.S. Postal Service officials warn it likely wouldn’t be delivered in time. Instead, deposit your ballot envelope in one of the secure ballot drop boxes around the county.

All ballot boxes will be accessible until 8 p.m. on Election Day, Tuesday, Nov. 3. Regular hours for other days listed below.

MARION COUNTY (Full list here):

Marion County Clerk, 555 Court St. N.E., Ste 2130 -8:30 a.m.-5 p.m. weekdays

Marion County Health, 3180 Center St. N.E. – Curbside (24 hours)

Roth’s Fresh Market, 3045 Commercial St. S.E. -6 a.m.-9 p.m. daily

Roth’s Fresh Market, 4555 Liberty Rd. S. – 6 a.m.-9 p.m. daily

Roth’s Fresh Market, 4746 Portland Rd. N.E. – 6 a.m.-9 p.m. daily

Marion County Public Works, 5155 Silverton Rd. N.E. – 8 a.m.-5 p.m. daily

POLK COUNTY (Full list here):

Roth’s Fresh Markets, 1130 Wallace Rd. N.W. – 6 a.m.-9 p.m. daily

TOP 5 VOTING MISTAKES TO AVOID

1. Fill out both sides of your ballot. You don’t have to vote in every race, but make sure you’re not overlooking the back of the ballot – or returning a blank ballot.

2. Don’t forget to sign your ballot envelope on the marked line.

3. Double-check you’re signing your envelope, not a spouse’s or roommate’s.

4. Don’t return your ballot late. After Oct. 27, ballots should not be mailed. Use a drop box.

5. Don’t ignore mail from the county clerk’s office. If you get a letter or postcard after the election, it’s likely because there was a problem with your signature which you can fix.

TRACK YOUR BALLOT: See when it’s received, processed

MyVote for all Oregon voters

BallotTrax for Marion County voters (requires registration with a phone number or email address)

VOTING QUESTIONS

Marion County clerk – (503) 588-5041

Polk County clerk – (503) 623-9217

ELECTION REPORTS: The voting process

Here’s what happens to your ballot after you drop it in an Oregon drop box

Ballots can take up to a week to reach a clerk’s office by mail, so election workers advise using a drop box starting Oct. 28 to ensure your vote is counted. So many voters are turning ballots in early that Marion County is now emptying many drop boxes twice per day.

VOTE 2020: Ballots go out this week for Oregon voters. Here’s how to make sure yours gets counted.

Signature mismatches and late ballot returns cost about 2,500 Marion and Polk county voters a say in Oregon’s 2018 election for governor. We asked elections clerks what you need to know for 2020.

Marion and Polk county clerks say they’re getting more questions ahead of this election as a record number of voters across the U.S. plan to vote by mail. But in Oregon, it’s business as usual.

While vote-by-mail is now popular in Oregon, Davidson said it took years to implement and to convince the public to embrace a practice that faced initial skepticism. Other states don’t have the same time.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Whether angry or hopeful, your ballot speaks for you. We’re here to help

EDITOR’S NOTE: Signs are that voter interest in the 2020 election is intense, judging by huge turnout in other states during early voting. Salem Reporter is doing what it can to help you understand how Oregon elections function and what’s being done to guard against fraud.

ELECTION REPORTS: Candidate profiles

Pierce is squaring off in a rematch with Democrat Paul Evans for a House seat covering west Salem and Monmouth. It’s a race that’s statewide attention. A former dentist, she wants to expand career and technical education while helping small businesses.

For the second time, the Monmouth Democrat will face off with Republican Selma Pierce. While Pierce is well-funded, other factors favor Evans.

Lyle Mordhorst was appointed a Polk County commissioner in January 2019 and points to various successes he’s had during that time, including key infrastructure projects. He’s running in the Nov. 3 election against retired U.S. Navy officer Danny Jaffer.

Danny Jaffer is running against Lyle Mordhorst, who was appointed a Polk County commissioner last year. Jaffer points to his career in the Navy as preparing him to work with those he doesn’t agree with by being willing to talk to them.

VOTE 2020: Danielle Bethell seeks restraint in county spending in bid for Marion County commission

Bethell, a Republican, is running against Democrat Ashley Carson Cottingham for Marion County commissioner in the upcoming election. The pair are approaching the role from two different backgrounds, one in the private sector and the other from her role in government.

The Democrat is making a bid for a seat on the Marion County commission that has been a Republican stronghold for decades.

Democrats have gained a small advantage in voter registration in the crescent-shaped district that includes south Salem and surrounding areas. But Republicans are hoping that there’s enough discontent with Democratic rule to help Boles keep the seat.

VOTE 2020: With a focus on health care, Deb Patterson makes another attempt to flip a Senate seat

Senate District 10, which includes south Salem and other areas, has long been held by Republicans. But with the longtime incumbent not on the ballot this year, Democrat Deb Patterson sees a chance. The race’s outcome could tilt the state’s political balance.

VOTE 2020: In her run for state representative, Jackie Leung wants to help Oregon’s marginalized

With a background in law and public health, Leung said she’ll work to improve education, housing and food insecurity. But Leung, currently a Salem city councilor, will have to flip a seat long held by Republicans. Democrats see reason for optimism.

VOTE 2020: Raquel Moore-Green says she’ll seek more accountability in Legislature if given full term

Long active in Salem’s business community and civic life, Moore-Green, a Republican, is running for a full term for a seat she was appointed to last year. She said she’ll seek to change how the Legislature does business.

SUPPORT ESSENTIAL REPORTING FOR SALEM – A subscription starts at $5 a month for around-the-clock access to stories and email alerts sent directly to you. Your support matters. Go HERE.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.