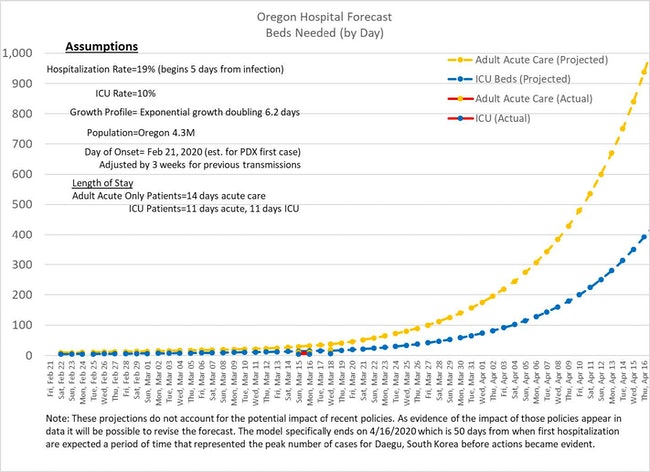

The estimated number of people likely to need hospital services in the state of Oregon, based on computer simulations performed by Oregon Health and Science University. (Source: OHSU)

NOTE: Salem Reporter is providing free access to its content related to the coronavirus as a community service. Subscriptions starting at $5 a month help support this.

For four million Oregonians, staying home now could save a life.

State health officials expect to see a rapid increase in the number of people infected with COVID-19, the respiratory disease that is mild for most people but deadly for the vulnerable.

They concede they have no idea how widespread is the disease now. They do know that hospitals don’t have enough beds or supplies to treat the pandemic that by Friday had killed four Oregonians.

In forum after forum, authorities urged Oregonians to sacrifice life’s routines to spare others. This is no time, they said, for half measures.

“If we under prepare and under react, more Oregonians will die,” said Dr. Danny Jacobs, president of Oregon Health and Science University.

The Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems had been pressing the governor to order people to stay home. Other professional health organizations joined that plea.

On Friday night, Gov. Kate Brown came close to doing so. She stopped just short of that at her evening news conference in announcing a new campaign: “Stay Home, Stay Healthy.”

“I am directing Oregonians tonight to stay home to stay healthy,” the governor said.

She made the declaration in a conference in which Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler and Multnomah County Chair Gretchen Kafoury participated. Wheeler said he expected to order the residents of his city to end all trips from home that could put people in contact with others. He said he hoped the state too would issue such an order.

The novel coronavirus is spread through human contact, particularly from people who sneeze or cough when infected. Symptoms can take up to two weeks to emerge, meaning people with the disease can be feeling well and conducting life as normal but unwittingly infecting others along the way. That accounts for what is called “community spread” – infections that aren’t traced to those who have traveled to countries with COVID-19 outbreaks or who weren’t known to be in contact otherwise with infected individuals.

“The healthy and optimistic among us will doom the vulnerable,” said Emily Landon, the chief infectious disease epidemiologist at University of Chicago Medicine. She spoke at a Chicago news conference as Illinois imposed its own stay-at-home order.

“It’s really hard to feel like you’re saving the world when you’re watching Netflix from your couch. But if we do this right, nothing happens,” Landon said.

The reach of any order in Oregon could become more clear with new state announcements expected on Monday.

Governors in California, Illinois, New York and Connecticut already have by law told their residents to stay home. Such orders have been termed “shelter in place” but Wheeler said the phrase is being dropped because it’s misleading, indicating people go home, seal themselves in and wait out the emergency.

Through the day Friday, authorities cast the need to stay home as a life-and-death choice.

The president of Salem Health, which operates one of the state’s largest hospitals, pleaded with her community in a statement hours before Brown’s news conference.

“Sheltering at home – while extreme – is critical,” said Cheryl Wolfe, a registered nurse for 46 years. “Without adequate testing, it is impossible for us to know who has the virus or where and for how long they’ve exposed others.”

Renee Edwards, OHSU chief medical officer, told legislators serving on a special committee that Oregonians need to “very seriously” engage in social distancing. That’s generally considered staying at least six feet away from others.

“Every Oregonian, especially healthy Oregonians, can take actions now that will literally save lives,” Edwards said.

DOCUMENT: Renee Edwards testimony

The governor Friday night said she was “urging Oregonians to save lives and stay home.”

The urgency to act in Oregon is driven by what medical professionals say they have seen in other countries and in other places in the U.S., including in Washington state.

As of Friday, Oregon had detected 114 infected Oregonians from the 2,550 tested. Results were pending for another 433.

The state is presumed to have had its first infected Oregonian on Feb. 1 and its first confirmed test on Feb. 28, according to Dr. Peter Graven, OHSU lead data scientist. His team has done projections for what Oregon is to face, but he told legislators those numbers are likely outdated.

“Those simulations will underestimate the number of hospitalizations,” Graven said.

DOCUMENT: Peter Graven testimony

He said health officials still expect the number of cases to double every six days. One out of five infected Oregonians will need to be put in a hospital.

He said under normal circumstances, Oregonians stay in a hospital five to six days. But those needing care for COVID-19 will stay 14 days and those needing intensive care will stay 21 days.

“The longer a patient needs to stay in the hospital, the less capacity a hospital has to take care of newly sick patients,” Graven said.

Jacobs, the OHSU president, explained the impact.

“Hospital beds and intensive care units will be full, and difficult decisions will need to be made around the placement and care of patients,” Jacobs testified. “Physicians, nurses and staff will become exhausted and many may become sick themselves.”

DOCUMENT: Danny Jacobs testimony

Oregon authorities say they are trying to add 1,000 hospital beds and 400 intensive care units to handle what Brown termed a coming “storm.” The Oregon Health Authority last week erected a 250-bed hospital in the commercial exhibit hall at the state fairgrounds in Salem.

Edwards, OHSU chief medical officer, noted that while eight out of 10 infected with COVID-19 will have mild symptoms, they still will be sick. They can get by with home rest and care, but Edwards said experience elsewhere shows that recovery takes about two weeks.

She said that will take many Oregonians out of their work and other routines and their needs will be another drain on medical resources.

Health officials and government leaders say that all builds the case to keep Oregonians away from each other. That’s the only way slow the spread and avoid the kind of dramatic spike in caseloads that would overwhelm medical resources.

Brown has steadily been escalating the mandates around the state. She ordered schools closed and then extended the order by a month. She ordered restaurants and bars to stop serving diners except by takeout or delivery. She has ordered no one be allowed in facilities that care for the elderly and disabled, meaning no visits to nursing homes, assisted living complexes or group homes.

While stopping short of an order to every Oregonian to stay home, Brown indicated she’s preparing to shutter even more businesses. She said employers who serve the public in ways that can’t be taken away in a box “need to close.”

Wheeler was the most explicit in describing what life could be like should the government order people to stay home. He was clear that people wouldn’t be sent home and not allowed out until the government said it was safe.

“This will be stay at home unless it’s absolutely necessary” to leave, he said.

In the order he has in mind, Wheeler would allow citizens to leave for key tasks such as getting groceries, buying gas and getting medicine. He said citizens could leave to take care of relatives or even go for a hike.

Kafoury, the Multnomah County chair, said group sports such as soccer wouldn’t be wise but people could still go jogging, cycling or skateboarding – keeping six feet away from others.

What was less clear was the impact on the businesses still operating. Throughout the state, major retailers such as Macy’s and REI have voluntarily shut down as have many small businesses.

In other states, restrictive orders have not applied to “essential” services. In Oregon, representatives of various industries and professions have already been lobbying to have their sector declared “essential.”

San Francisco was one of the first places to shut down under a stay-at-home practice. “Essential businesses” there included grocers, gas stations, hardware stores, banks, laundromats and businesses that sell supplies that allow people to work from home.

DOCUMENT: San Francisco order

Les Zaitz is editor of Salem Reporter. Email: [email protected]