Hallman Elementary students gather during the school’s morning assembly. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

Hallman Elementary students gather during the school’s morning assembly. (Fred Joe/Special to Salem Reporter)

Thousands of students facing challenges to succeed in school could be helped with changes proposed by parents and others in recent sessions held by the Salem-Keizer School District.

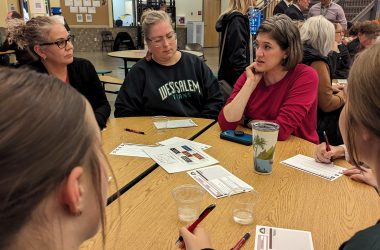

Hundreds packed into school libraries and conference rooms over past weeks to weigh in on how the district should spend millions of state money.

They shared stories about their families’ experiences in local schools: how leadership classes have helped a struggling student blossom and describing how an autistic child becomes easily overwhelmed in a classroom with 30 peers.

And they absorbed lessons from district administrators, who outlined where Salem-Keizer struggles: low graduation rates for Pacific Islanders and students with disabilities, black and Native American students reporting they often feel unwelcome in school.

“This data can be troubling, but it’s important,” said Olga Cobb, an elementary school director, speaking in Spanish at a gathering for parents of bilingual students. “We want to know from you, are we doing a good job? And if not, how can we improve?”

[ Help build Salem Reporter and local news – SUBSCRIBE ]

This report is based on observations from community meetings, interviews with facilitators and district employees and the district’s written summaries.

School administrators expect the district to receive about $35 million next fall as part of the Student Success Act.

By law, that money must be used to reduce academic disparities for particular groups of students who have historically struggled in school. Superintendent Christy Perry wants local spending to benefit students who are black, Pacific Islander and Native American, from low-income families, have disabilities, learning English, homeless or in foster care.

About four in five Salem-Keizer students fit into one or more of those groups, district data shows. And some students face multiple challenges to succeeding in school.

Nearly 1,200 students are from a low-income family, learning English, have a disability and are not white, district data shows.

Meetings with parents and citizens from those groups continue into early December.

A community task force led by volunteers Adriana Miranda and Reginald Richardson will meet next in mid-December to review community comments and begin crafting a plan for spending the money.

Though they face distinct challenges, parents and students from many of the targeted groups spoke about similar solutions or resources needed to improve local schools.

Improve inclusion and accessibility at schools

Whether because of their race or a disability, many parents said their students don’t always feel welcome at school or have adults they can connect with.

Black parents said their children are more likely to be judged by teachers or get in trouble for something other students do without consequence. They agreed Salem-Keizer needs a more diverse teaching workforce.

That feeling is compounded by curriculum. Outside of a club at McKay High School, there are few ways Pacific Islander culture is incorporated in the classroom. Black and Native American history is often simplistic, focusing only on major civil rights leaders or teaching that Columbus discovered America.

Parents who don’t speak English said connecting with their child’s school can be difficult. Even when elementary school math homework is in Spanish, parents don’t always know how to help because the problems are very different from what’s taught in Mexico, several said.

And some classes are taught in ways that make learning difficult for students with disabilities though they’re capable of understanding the material.

“There’s kind of a one-size fits none approach to learning,” said Cori Mielks, who has a son who’s a sophomore in high school. He struggles with auditory processing, she said, so classes taught entirely as lectures don’t work well for him.

She echoed many parents who said they wanted to see teachers trained on universal design, where lesson plans are created to suit many different methods of learning.

Baudelina Chavez said her daughter struggled with her English proficiency exam in elementary school because she uses a hearing aid and couldn’t hear spoken questions well.

She passed once she could take the test in a quieter environment, but Chavez said school employees should proactively consider barriers like that, not wait for parents to advocate for their children.

Sports and other activities are hard for some students to access

Last year, nearly 98% of Salem-Keizer high school seniors who played a sport graduated.

But sports and other activities remain out of reach for low-income and non-English speaking students, parents said.

Districtwide, seven in ten students are from low-income homes. Only about half of students playing high school sports are. Activity fees, uniform costs and transportation needs can all keep kids from participating, parents said.

Even if financial help is available, the gap can start younger. Low-income families may have trouble enrolling their kids in youth sports or outside leagues in elementary and middle school. By the time children reach high school, they may not have enough experience to play.

Many parents also mentioned art, music and other creative outlets they’d like to see become more accessible, or included as part of the school day. Currently, no elementary school has an art teacher.

Keep schools open longer

Many participants said students would do better if they could stay at school longer for extra academic help, after school activities or simply a safe place to be.

For students where families can’t afford computers or graphing calculators, having access to technology after school would make a difference in academic performance. Homeless students in particular struggle to finish homework when their family is living in a car or shelter.

Giving kids a place to be after school can also help keep them out of trouble.

Working parents also struggle with later elementary school start times, since many have to be at work well before 9 a.m. Letting them drop kids off at school earlier could improve attendance, some suggested.

Class size matters

Individual attention for struggling students was something many parents said helped their child succeed.

But classes of 30 or more students mean such focused attention isn’t always available.

One mother spoke about her autistic son, who got easily overstimulated in a classroom with so many children. Others said larger class sizes made it difficult for kids learning English to get the help they need.

Melissa Glover, the district’s student services coordinator, said many parents of students with disabilities said they want to see a reduced caseload for special education teachers so their students can get more help.

Smaller class size was one of the top three academic priorities for many of the groups that district employees spoke with.

Reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.