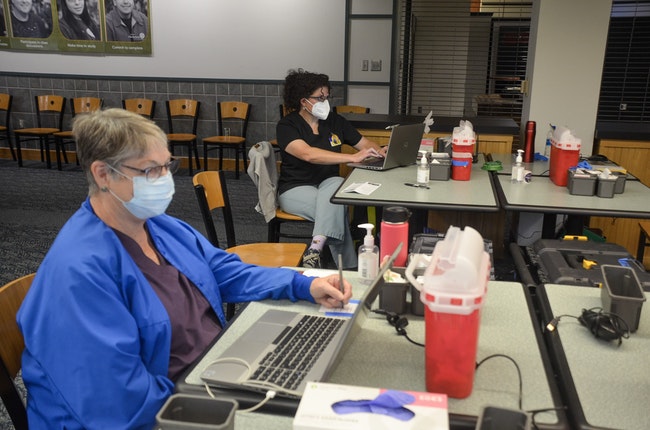

Nurses staff a mobile vaccine clinic in Salem (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

More scholarship money and perhaps tax credits would help stem Oregon’s nursing shortage, according to nursing students and deans of Oregon nursing schools.

In an one-hour online discussion on Wednesday, they told U.S. Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Oregon, that having enough money to pay for housing, food and other necessities and pay for their education is one of the biggest barriers students face in nursing school. Even those who benefit from Pell grants or federal funding through Title VIII, which prohibits discrimination at institutions, can end up with big debts when they graduate.

“I don’t think we can overstate the importance of Title VIII funding,” said Susan Bakewell-Sachs, dean of Oregon Health & Science University’s Nursing School. She said in the 2021 fiscal year, Oregon students received about $2.6 million in such funds.

“We are a state that benefits directly from this,” Bakewell-Sachs said.

Oregon needs to graduate more nurses to meet the demand. The state Employment Department estimates that Oregon needs to graduate 2,500 nurses a year to have enough to treat patients. It’s falling hundreds short. Health care systems have relied on bringing in out-of-state nurses, but that source is diminishing.

Bonamici said she has deep interest in Oregon’s nursing shortage. She’s co-vice chair of the House Nursing Caucus and serves on the Education and Labor Committee. She said she especially wanted to hear from students.

Jacob Goeringer, a senior nursing student at George Fox University in Newberg, said during the discussion that the pandemic strengthened his commitment to nursing.

“It actually increased my desire to continue in this course and to (have) a positive impact in my community,” Goeringer said. “We need nurses.”

But he said he had difficulty obtaining financial aid.

“There are not many external scholarships that were available to me – even as a minority, being a male in the nursing profession,” Goeringer said.

Educators said Oregon also needs more faculty. The discussion included three educators: Bakewell-Sachs; Pam Fifer, associate dean of nursing at George Fox University in Newberg; and Linda Campbell, dean of Warner Pacific University’s nursing school in Portland. Jana Bitton, executive director of the Oregon Center for Nursing at the University of Portland, took part as well.

At George Fox, the dean and associate dean of nursing have to teach because of a lack of faculty, Fifer said.

According to the nursing center, associate and bachelor degree programs in Oregon graduated just over 1,400 nurses in 2014. That jumped to nearly 1,800 in 2021. But the number of faculty both years stayed at 720.

“Scholarships and student aid are important, but we won’t be able to increase the number of nurses we graduate in the state without addressing the difficulties we have recruiting nurse faculty,” Bitton told the Capital Chronicle after the discussion. “We need to be more intentional about our solutions to nursing education capacity, and take a more collaborative approach to growing our health care workforce with industry leaders and government agencies.”The state has difficulty attracting enough faculty members because of the pay, they said. Nurses earn more money working in a hospital or clinic than teaching.

That means that even nurses who are passionate about teaching often don’t pursue an academic career.

“I know of several excellent nurse educators who’ve said ‘I have to go back to the bedside,’” Fifer said. “They were the primary breadwinner in their family, and they could not afford the salary of a nurse educator.“

Bakewell-Sachs said a federal center devoted to nursing education, increasing the number of nursing faculty and the number of clinicians supervising nursing students would help.

The nursing shortage has reduced the clinical opportunities for students, experts say. With the current shortage of all health care staff, nurses say they often have to answer the phones, take meals to patients or perform other duties they normally would not do. That leaves little time for them to supervise students.

Yet students need clinical experience to graduate. The University of Portland has a mock clinic on campus to give students experience.

Child care is another hurdle, the students said.

Itai Muszongo, a nursing student at Warner Pacific University, has two children. Continuing her nursing studies was especially hard during the pandemic, she said.

“I was homeschooling my kids and I suppose homeschooling myself, trying to keep up with my assignments, trying to keep up with their assignments,” Muszongo said. “It was quite a juggle.”

She said there is more day care now but it’s expensive.

Anna Abel, a junior nursing student at OHSU, has a daughter in kindergarten. She said the only way she could stay in school during the pandemic was to use OHSU’s child care center. Now she’s having a hard time finding care after her daughter’s school day.

“After school care is so hard to get into. We’re on a long wait list,” Abel said.

Bonamici said there needs to be work-study programs to allow students to pursue a career in nursing.

“We need fewer barriers, not more barriers,” Bonamici said.

She said her policy priorities include increasing Pell grants and forgiving more federal loans. But Fifer said loan forgiveness is not the answer to solving the faculty shortage.

“It doesn’t work for all faculty because I think it’s income based,” Fifer said.

She suggested tax credits as a way to give educators more money.

Oregon Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oregon Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Les Zaitz for questions: [email protected]. Follow Oregon Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.

STORY TIP OR IDEA? Send an email to Salem Reporter’s news team: [email protected].