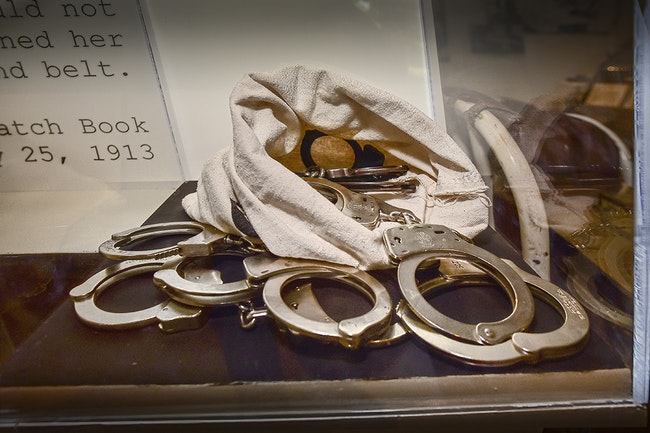

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes a display of restraints once used to manage patients at the Salem institution. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

In centuries past, the stigma and ignorance surrounding mental illness contributed to the often barbaric treatment of those who were suffering.

Patients were chained in dark, unsanitary cells, had portions of their skulls removed, were forced to vomit repeatedly and endured regular bloodlettings.

Now in most settings, humane treatment of the mentally ill is commonplace.

To illustrate the advances made over the years in the techniques and tools used to treat the mentally ill, volunteers in 2012 established the Oregon State Hospital Museum of Mental Health, said Kathryn Dysart, a docent and a founding member of the museum’s board.

Photographs, objects, personal histories and a timeline that takes up an entire room enables visitors to understand the progress and challenges associated with mental health treatment in Oregon from the 1850s through today, she said.

The treatment of the mentally ill can be difficult to take in.

In Salem and elsewhere, past attempts to return patients to “normal,” meant that they sometimes were shackled, submerged in ice-cold water baths, given electric shock treatments or were restrained in straightjackets.

Some of the instruments associated with those treatments are on display at the museum, including a surgery table used for lobotomies, handcuffs, a straightjacket and leg restraints.

It was in the mid-1800s that physician Thomas Kirkbride of Pennsylvania pioneered changes in the treatment of mental illness, Dysart said.

His plans for designing asylums to support humane treatments were used in Salem and across America.

In recognition of Kirkbride’s philosophy, the museum is in a building on Northeast Center Street that is named for him.

“He believed and spoke to the notion that if you put people in an environment that is peaceful, beautiful and filled with fresh air and sunshine they would improve,” she said. “He crusaded against placing people in dungeons.”

Many of Kirkbride’s reforms remain in use today, Dysart said.

Views concerning the mentally ill have changed over the years so museum curators selected items to teach that patients are more than statistics.

In the Brooks Room, named for former Superintendent Dean Brooks, information is available concerning patients who died in the hospital. There also are details about the victims of suicide, murder, violent attacks and an accidental mass poisoning.

The room is used to highlight the stories of current and former patients to “bear witness and give voice to the hospital’s history,” Dysart said.

Kathryn Dysart is a docent and founding board member of the Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The room also contains materials about deceased patients, whose cremains are held in 3,000 canisters in a separate building.

Another way to bring patients to life, are the large charts that list initial diagnosis, gender, occupation, ethnicity and suspected causes of insanity.

Alongside the charts are recordings and photographs to remind visitors that the people kept in the hospital were valuable human beings.

There also are displays detailing why work was considered an essential part of therapy.

There is a large kettle in which residents helped prepare food. There are sewing machines, looms, tools and objects explaining how patients raised meat and produce on two state-owned farms.

Oregon’s forays into caring for the mentally ill began in the 1850s when the Oregon Legislature authorized payments to citizens to house and feed indigent patients living in their homes, she said.

Then in 1861, Dr. James Hawthorne built a private hospital for the insane in Portland, but staying there was costly.

In 1883, the state opened the Oregon Insane Asylum in Salem.

Over the years, people were committed for all types of behaviors, including being feeble minded and suffering from ailments as diverse as tertiary syphilis to senile dementia. Some women were sent to the hospital by their husbands for being recalcitrant, mouthy, having post-partum depression or for either being frigid or too sexually active, Dysart said.

A number of Native Americans were placed in the hospital for “talking” to their ancestors, while some immigrants were admitted to the hospital because they did not speak or write English so they couldn’t answer questions about their welfare.

During the Depression, a number of those hospitalized had been only malnourished, consequently becoming mentally unstable. Once they were hydrated and got something to eat, they were released.

In the 1960s, the state started placing more of the mentally ill in community settings, often with inadequate funding to fully care for them.

Consequently, many of those who couldn’t and today can’t afford to pay for care or have not been adjudicated to the hospital by the courts wind up homeless.

Most of those at the state hospital are court committals. Currently, the hospital’s population is just under 700.

Instead of being housed as before in dormitories, patients now stay in private or semi-private rooms situated in pods. The new housing arrangement allows patients to benefit by interacting with staff and nurses.

Gone are the straight jackets and shackles having been replaced by treatments coupled with anti-depressants, anti-anxiety medications, mood stabilizers and antipsychotics.

There are group and individual therapy meetings, art and music programs, exercise classes and yoga and meditation opportunities, Dysart said.

All treatments dovetail with the philosophy of treating people with respect, she said.

Visitors to the 2,500-square-foot museum come for a variety of reasons.

Many visit because they, family members or friends have personal experiences with depression, addiction or other diagnoses, Dysart said.

Because of stigmas surrounding mental health, frank discussions about those issues weren’t previously possible. Now those visitors can get a better understanding of their lives.

“Many stop to tell our volunteers about their own history, sometimes with great emotion,” she said.

Others visit because they are “interested in the enormous institution that has played such an important role in Salem’s history,” Dysart said.

Some are drawn to the museum to see the exhibit based on the award-winning movie “One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest,” which was filmed there in 1975.

The film was based on Ken Kesey’s book that explores institutional overreach and the dehumanization of the mentally ill.

Museum visitors can take docent-led tours or do their own exploring. The cost to visit is $7 for adults, $6 for students and seniors and members get in free.

Currently, the museum is closed because of COVID-19, but Dysart hopes to reopen later in the fall.

For more information about the museum and to learn how to volunteer and/or become a board member visit the museum’s website at oshmuseum.org.

A strait jacket once used to control patients at the Oregon State Hospital is part of the Museum of Mental Health. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

A strait jacket once used to control patients at the Oregon State Hospital is part of the Museum of Mental Health. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes a recreation of what was once a typical patient’s room. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes a recreation of what was once a typical patient’s room. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes a surgical table used for performing lobotomies. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes a surgical table used for performing lobotomies. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

Among the artifacts at the Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital is a device once used to give electroshock therapy to patients. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

Among the artifacts at the Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital is a device once used to give electroshock therapy to patients. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes artifacts from the filming of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” including this photo of stars Jack Nicholson and Will Sampson. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health at the Oregon State Hospital includes artifacts from the filming of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” including this photo of stars Jack Nicholson and Will Sampson. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health is housed at the Oregon State Hospital campus in Salem. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

The Museum of Mental Health is housed at the Oregon State Hospital campus in Salem. (Ron Cooper/Salem Reporter)

Contact Salem Reporter with tips, story ideas or questions by email at [email protected].

SUPPORT ESSENTIAL REPORTING FOR SALEM – A subscription starts at $5 a month for around-the-clock access to stories and email alerts sent directly to you. Your support matters. Go HERE.