(Illustration by Anna CK Smith/Special to Salem Reporter)

The classroom assistant was returning from lunch when a colleague asked her for help with a student who was biting and hitting.

She worked with another teacher to move the elementary schooler into an empty classroom.

“I was asked to help hold his head so he wouldn’t bite,” the aide wrote in her later report. When the other teacher let go of the boy, he began to target the assistant.

“He kicked me in the knee, causing me to fall forward and then when I was down he hit me in the face causing me to cut my lip and fall back on my elbows,” she wrote.

She left the school for medical care for injuries caused by the student and missed several days of work, district records show.

She’s far from the only one facing assaultive students.

This school year alone, students injured school employees of the Salem-Keizer School District 580 times, more than three injuries per school day.

Those injuries caused nearly 300 missed days of work and more than $90,000 in workers’ compensation claims, according to records Salem Reporter obtained through a public records request.

In a district with 2,000 teachers and 1,200 educational assistants in 65 schools, most employees go through the day without being injured by a student.

But for those who have been hurt, especially repeatedly by the same student, the costs can be high.

Schirle Elementary teacher Jamie Keene marches at the Oregon Capitol on February 18, 2019 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Schirle Elementary teacher Jamie Keene marches at the Oregon Capitol on February 18, 2019 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Veteran teachers and instructional aides who have spent a decade or more in the classroom said in interviews they dread coming to work, have been diagnosed with anxiety or are thinking about leaving the profession because of the frequency and severity of student aggression and extreme behaviors.

“We feel like we’re battling a battle we can’t win because we don’t have the tools to win it,” said Carol Viegas, a fourth-grade teacher who’s been at Pringle Elementary School for 20 years. “Each year things are escalating.”

To address the problem, the school district created an office of behavioral learning that oversees teams of staff trained to deal with students with especially extreme or challenging behavior.

The district this year started tracking student-caused injuries after hiring a new risk manager, something employee unions welcomed.

“It’s a big concern and we’ve worked really hard to respond,” Superintendent Christy Perry said. “I don’t think we’ve quite solved the problem yet.”

But educators say district efforts fall short.

They want more done to keep educators safe from students who have repeatedly attacked them, and time freed in their days to fill out injury reports so district data is accurate. They want parents to be more fully notified when there’s a disruption in class.

Many said they simply want to feel the district is taking their concerns seriously about the toll of student behavior on staff.

“Everything feels like a Band-Aid right now,” said Carole Allred, a teacher at Leslie Middle School.

The injuries

Injured employees include instructional aides, teachers and sometimes administrators in nearly every school in the district. Those affected include both special education and general education staff.

Records show most reported injuries don’t require medical care. Bruises are the most common reported injury, followed by abrasions. Injuries that require care typically result in little or no time off.

But staff narratives of the incidents show that even in cases where the resulting injury is a bruise, educators are being kicked, punched, bitten, headbutted and groped.

“Student was not following directions in the computer lab and while I was trying to turn off the computer, student punched me in the eye,” reads one report from an aide at Pringle Elementary School.

“I was scratched and pinched on the wrist and forearm. Skin was broken. I was punched in the crotch and kicked in the shins,” an employee at Sumpter Elementary School wrote.

Jamie Keene, a fourth-grade teacher at Schirle Elementary School, had several students in her class in recent years who repeatedly hit and grabbed her, once resulting in a trip to urgent care for a pulled muscle in her back.

She marched at the Capitol in February urging better funding for counselors and support staff, carrying a sign reading, “I didn’t go to college to be a punching bag.”

Salem-Keizer Education Association President Mindy Merritt, center, and vice president Tyler Scialo-Lakeberg, to her right, stand with members outside the Oregon Capitol on February 18, 2019 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Salem-Keizer Education Association President Mindy Merritt, center, and vice president Tyler Scialo-Lakeberg, to her right, stand with members outside the Oregon Capitol on February 18, 2019 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Keene said the repeated injuries are demoralizing and frustrating for her and impact the other students in her class when she has to stop teaching to address one student acting out.

“Your child is going to be ill-prepared for next year because I spend more time putting out fires,” she said.

And being hurt by a student is different than a trip or a fall resulting in the same injury, educators say.

“We’re not addressing the emotional injury,” said Mindy Merritt, president of the Salem-Keizer Education Association.

That includes the impact on other students in the class who witness assaults.

“It has an impact when they witness the adult in the classroom, the educator, their support staff being abused,” Merritt said.

Student discipline for specific incidents is difficult to track because student discipline records are confidential under federal and state law, and reports of staff injuries aren’t tied to records about action taken about the student.

The district focuses on identifying the underlying reason a student acts out and finding a way to address that, rather than punitive consequences like suspension.

“We know that suspension, expulsion doesn’t change student behavior. What we’re finding is it actually increases student behavior and also causes friction between families and school teams,” said David Fender, who runs the office of behavioral learning.

“If it’s a situation where there’s a concern that other kids, their safety could be in jeopardy or staff … oftentimes we’ll provide additional adult support for that classroom,” he said. A school team may also meet to review or create a behavior plan for the student.

A statewide problem

The problem is not unique to Salem-Keizer, or to Oregon. Stories of extreme student behavior were one of the catalysts for the Student Success Act, a $2 billion education funding package approved by the Oregon Legislature.

Portland TV station KGW over the year produced a series reporting on “Classrooms in Crisis,” and a report from the Oregon Education Association released in February said the state has a “crisis of disrupted learning” based on interviews and surveys of teachers around the state.

But accounts of the problem have been largely anecdotal, based on surveys of educators and individual stories. Such accounts typically recount the impact on students in missed class time rather than the demoralizing and traumatizing effect assaults can have on educators.

Efforts are underway in Salem-Keizer and around the state to improve reporting and better quantify the problem, but there’s currently little information available outside of injury reports from individual districts.

The Oregon Department of Education doesn’t collect data on teacher injuries or room clears, a practice where a teacher moves students out of a classroom to keep them safe because a student is throwing furniture or behaving aggressively.

Most school districts, including Salem-Keizer, don’t track such incidents. A bill introduced in the Oregon House this year would have required such tracking, but never progressed.

Salem-Keizer began tracking staff injuries caused by students in the fall of 2018 after hiring a new risk manager.

Merritt said the change was something the union’s members wanted, along with the change to an online form to report injuries.

Several other districts around the state have begun doing the same, said Bob Estabrook, government relations specialist for the Oregon School Employees Association, which represents about 20,000 school workers around the state, though not in Salem-Keizer.

Salem Reporter requested five years of data on worker’s compensation claims and injury reports from the Salem-Keizer district to document the scope of the problem.

Records from earlier years don’t list whether injuries were caused by students but do document when injuries are human-caused. For the one year that more detailed injury data was available – for the 2018-2019 school year – 96% of human-caused injuries were caused by students.

Reports of human-caused injuries have nearly quadrupled in the last five years, the data shows, from 153 incidents during the 2014-15 school year to 606 in 2018-19.

Some of that is due to a push to better document student-caused injuries, including the new automated system implemented in the past year which allows staff to report injuries online.

But educators agree the frequency of such incidents has increased dramatically over the past five years.

(Graphic by Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

There’s no one reason. District leaders and educators point to trauma related to early life experiences in the home, including poverty, family stress and in some cases, abuse.

Several educators said a rigidly structured school day, with little time for recess or play, contributes.

In 2014, Salem-Keizer cut kindergarten recess time at many schools, and educators said overall students have less time to play than they did a decade ago. Instead, students take more “brain breaks” – a brief structured period for stretching or physical movement in class before going on to a new lesson.

But teachers said unstructured play time, where kids can practice social interaction and be creative, is being lost.

“We can’t expect five-year-olds and six-year-olds and seven-year-olds to be sitting all day long,” Merritt said.

Higher academic standards, and a push from the district and state to have kids achieve at grade level, causes student stress.

“They care about scores and curriculum,” Allred said of the district. “Behavior has to be under control for any of these things to be effective.”

Even with data now available, educators agree the reported incidents seriously undercount the scope of the problem.

Viegas said employees know the forms are important, but often don’t fill them out because of lack of time or a sense nothing will be done.

“We all know that the data the district is getting isn’t accurate,” Viegas said. But when nothing changes based on her reports, it’s hard to feel it’s worth the time.

“I don’t have five minutes. What am I supposed to do with my 30 kids?” she said.

Photos of educator injuries collected by teacher Carol Viegas with excerpts from injury reports filled out by Salem-Keizer staff (Photo illustration by Anna CK Smith/Special to Salem Reporter)

Merritt said the union’s next step is to ensure teachers have time to fill out the form and take a break after an incident.

“There is no time set aside, even five minutes, to go and catch your breath. You are expected to just get back to work,” she said.

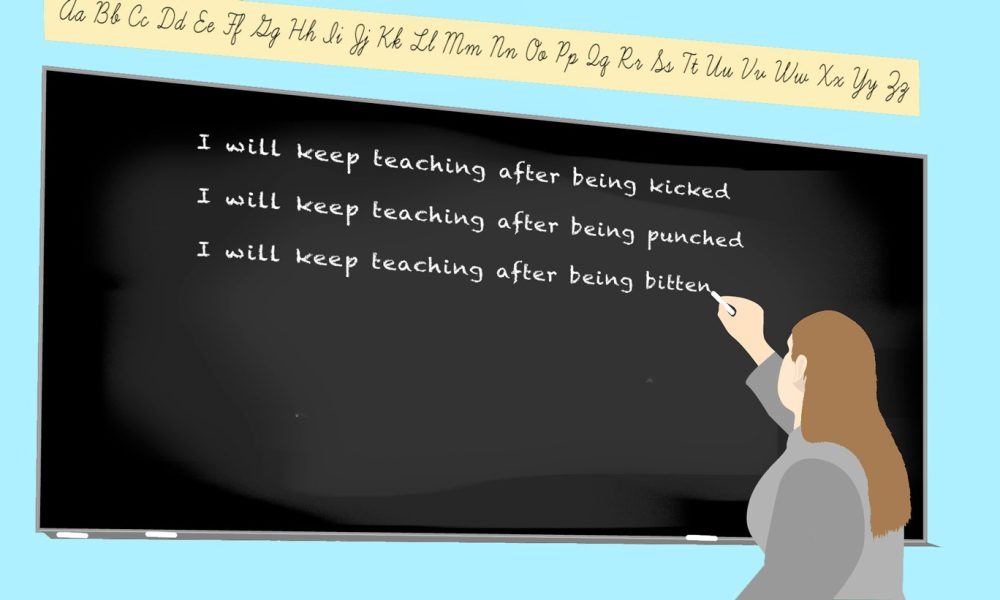

As a result, she said teachers have gone back to teaching a room full of kindergartners while fighting back tears and holding an ice pack over a fresh bite.

“Tears in their eyes and they keep on teaching,” she said.

District spokeswoman Lillian Govus said district leaders have asked Merritt for the number of employees who don’t have time to fill out the form and were told they didn’t have an estimate. She said the increase in reported injuries indicates most employees are finding time to make injury reports.

Fear is also driving staff to under report injuries. Several educators said they worry about retaliation from administrators for reporting their injuries, whether through explicit means like a worse performance review or simply creating a perception they can’t do their jobs well.

“An injury report shouldn’t mean that you’re not effective in your position,” Merritt said.

Govus said injury reports aren’t shared with human resources and have no bearing on an employee’s contract.

Merritt said some administrators have tried to define what “counts” as an injury, something the union is opposed to.

“The message is: if you feel it’s an injury, you need to report it,” she said. For Merritt, that includes incidents that may not leave pain or visible marks but are still assaultive, like when a student grabs a teacher’s breasts or genitals.

Improving behavior

Perry said the district has put a growing emphasis on teaching students social and behavioral skills like emotional regulation. That include creating the behavioral learning office in late 2017 and starting a district system for teaching students to identify and regulate their emotions.

“I wanted to put our attention squarely on the impacts our kids were having from trauma,” Perry said of the office’s creation.

Salem-Keizer Superintendent Christy Perry (Moriah Ratner/Special to Salem Reporter)

Fender, the coordinator of that office, started at the district 18 years ago and previously worked in special education.

About three years ago, he noticed more students were being placed in full-time special education classrooms. Early in his career, two or three students in a building might qualify. A few years ago, that number had grown to two or three per classroom.

“We were seeing an uptick in the number of kids who were entering school having a hard time regulating their emotions, sometimes manifesting in physically aggressive behavior,” he said.

Part of the problem, he said, was students couldn’t get help with behavior or social skills outside of a special education diagnosis. He began talking to Perry about a more proactive approach to give all students help with emotions and behavior.

That includes a system to track behavior referrals at each school. Students can have “minor” or “major” behavior reports, and a school team should regularly identify students who repeatedly have problems and determine how to reduce such instances.

“Kids should have healthy consequences and that should be part of the conversation,” Fender said. Under the proactive approach his office takes, those consequences typically aren’t suspension or expulsion. Instead, a student may be asked to clean up a bookshelf they knocked over or help with another task around the school, like raising and lowering the flag with the custodian.

More elementary schools now have a “behavior cadre,” employees trained in working with students with severe behavioral problems. When the district ended up with extra money in its budget for 2019-20, Perry spent about $2 million on additional behavioral staff and counselors, mostly for elementary schools.

And funds from a $2 billion education spending package passed this year can be set aside for addressing student behavior, though that money won’t be available until the 2020-21 school year.

Teachers say having extra behavioral staff has helped them because those staff can take problem students away and give them a break. But several said the behavior specialists and other staff at their schools spend much of their time dealing with a small number of very difficult students, leaving them feeling they can’t ask for help with their own classes.

Several said pointed schools can’t or won’t discipline students who repeatedly injure employees or take steps to keep them away from the person they’re injuring.

“Kids are not being held accountable for their actions,” said one classroom aide, who was repeatedly punched in the face by a teenage student. The aide asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation for speaking about that experience.

“We’re teaching them that it’s okay to be violent. We’re raising kids to not be accountable when they’re older,” the aide said.

Fender disagreed, citing the behavior teams in schools that review student actions and identify “appropriate consequences.”

“Building principals may decide that suspension is warranted, but other restorative approaches will be considered prior to excluding students from the school setting,” he wrote in an email.

Educators can call school resource officers or police if they believe an assault warrants it. Students have been charged with assaults, Govus said, though the district doesn’t track how frequently that occurs.

Educators also can transfer to a new job or classroom if there’s a particular student who’s repeatedly injuring them, Govus said.

Educators said they want to support students with special needs, and several who spoke to Salem Reporter are themselves parents of students with disabilities.

But they said the current system too often returns students to their classrooms minutes or hours after they’ve been injured, which can be traumatic for them and for other students who watched an assault.

When students act out or assault someone, they may be pulled from the classroom and given time to get their emotions under control, or staff may do a room clear and leave the disruptive student in the room.

That student may do an activity like deep breathing to calm down before returning to class.

“Sometimes they come back into the classroom with a snack. For those kids trying to do the right thing, it really gives them the wrong message,” Viegas said.

Students who injure staff may have a note sent home to parents explaining the behavior, but there’s often no requirement the parent acknowledge the note or talk with staff.

“You’re not making the parents responsible for your child’s behavior,” Keene said.

Govus said notes and conversations with parents can all be part of a student’s behavior plan, which is determined through the school’s behavior team.

Educators said they want better systems in place for notifying parents when assaults or disruptions happen in the classroom.

Schools routinely call parents to report when a building goes into lockdown because police are chasing a criminal suspect several blocks away.

McKinley Elementary Principal Michelle Nelson sent a recorded call to parents in May after a student hit her and another student. But such calls aren’t routine.

Allred said her daughter witnessed an assault in her second-grade classroom.

“She watched another student hit the teacher in the face,” she said. As a parent, Allred wasn’t told of the incident. She found out because her daughter happened to mention it.

Keene said most parents would be more concerned about a violent incident in class than a police matter a few blocks from school.

“Why aren’t they being called every time a teacher is being hit and a chair is being thrown?” she said.

Govus said McKinley parents were vocal about wanting to be told of such incidents, but parents at other schools have said they want fewer phone calls by schools. Principals and administrators can decide whether to make such calls routine based on their sense of the school’s parents, she said.

District training has focused on how to prevent students from becoming agitated to the point where they start attacking teachers or other students. Educators said that’s useful, but they need to know what to do when a student is out of control.

“None of us are trained in any of this,” Allred said.

Fender said the office of behavioral learning trains all district staff on topics including social and emotional learning and positive behavior intervention.

About 2,000 employees have received additional training on student behavior through a course where 85% of the time is spent on prevention, while 15% is on dealing with aggressive students in the moment.

Several educators said they felt Salem-Keizer is more concerned with saving face than having an open discussion of the scope of the problem.

Public statements and presentations about the need for better behavioral support in schools tends to focus on the impact to students in lost instructional time, and the needs of the kids acting out.

Those things are important, educators said, but they’d like to see more acknowledgement of the stress and trauma they experience from being bitten, cursed at, groped and attacked in class.

“One thing I think teachers want is they just want to be heard,” Allred said.

Perry said the district does take injury reports seriously.

“From an employer perspective I think it’s a problem any day you have people get hurt on the job,” she said. “We worry about those things all the time.”

Govus said the money spent on additional behavior staff and efforts to improve reporting show the district’s commitment to addressing injuries.

Viegas said she hasn’t had an assaultive student in her class for several years, but she still sees the impact at school. This year, a teacher in the neighboring classroom had a student who regularly injured her, so Viegas ended up helping her by covering her class or working with that student when other staff weren’t available.

She thinks administrators and school board members are too far removed from the classroom to have a full picture of the impact even one or two disruptive students can have on classrooms.

“I’ve seen a big disconnect between what is happening in our classrooms and what the district thinks is happening in our classrooms,” she said.

She began collecting photos of bite marks and scratches from colleagues this year.

“I’m tired of keeping the secret because people I care about are getting injured and these kids need help,” Viegas said.

Reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

LOCAL NEWS AND A LOCAL SUBSCRIPTION — For $10 a month, Salem Reporter provides breaking news alerts, emailed newsletters and around-the-clock access to our stories. We depend on subscribers to pay for in-depth, accurate news. Help us grow and get better by subscribing today. Sign up HERE.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.