I always thought that historically Valentine’s Day was celebrated by early Salem residents in the late 1800s in much the same way as it is celebrated now.

I imagined lacey cards were exchanged with loved ones, as well as flowers and other treats. I knew about Esther Howland, known as the “Mother of the American Valentine,” who is credited with creating the first mass market printed Valentines in the U.S. beginning in the mid-1800s. She designed her first cards while she was a student at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, where I almost went to college.

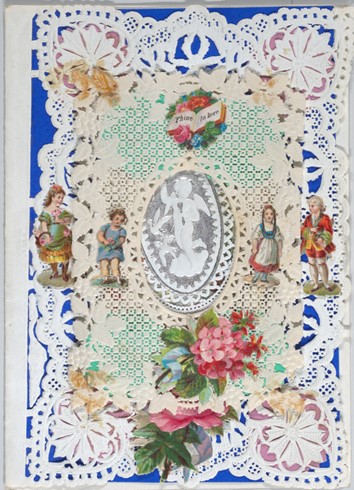

She designed a line of Valentine’s Day cards featuring lacey cut-outs and intricate illustrations. She used papers and illustrations imported from Europe through her father’s stationery business. Howland inspired me, because she was an independent and successful businesswoman, which was rare during this period.

Michele Karl, in her book “Greetings With Love: The Book of Valentines”describes Howland as one of the first employers to pay women a decent wage. In the early days of her business in Worcester Massachusetts, women worked out of the third floor of her home, gluing together images of frolicking couples, or girls and cupids together with flowers, lace and paper.

The industrial age brought machines that allowed for the mass production of these cards. Most significant was the machine-printed lithograph. In 1881, George C. Whitney bought her company and continued production of these kinds of Valentines on a mass scale, many of which I’m sure made their way to Salem.

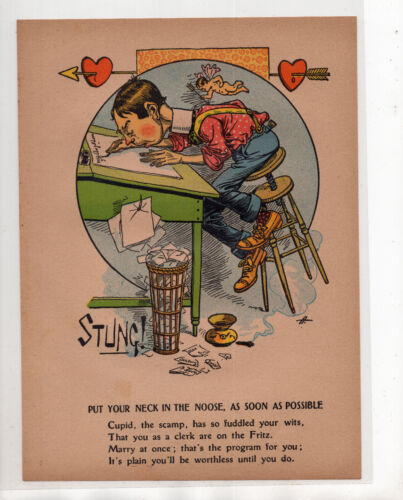

However, I was surprised to learn recently about John McLaughlin, a Scotsman who had thriving book and printing business in New York City around the same time, who introduced the first Vinegar Valentines in the mid-1850s as an antidote to these sentimental lacey cards.

In the Victorian era, there were actually two types of commercially produced valentines. There were the lacey, flowery, and sentimental types like Howard and Whitney produced, and then the comic or Vinegar Valentines which usually included an insulting poem and caricature illustration. During the mid to late 1800s it was a tradition not only to send valentines to loved ones, but also to your enemies.

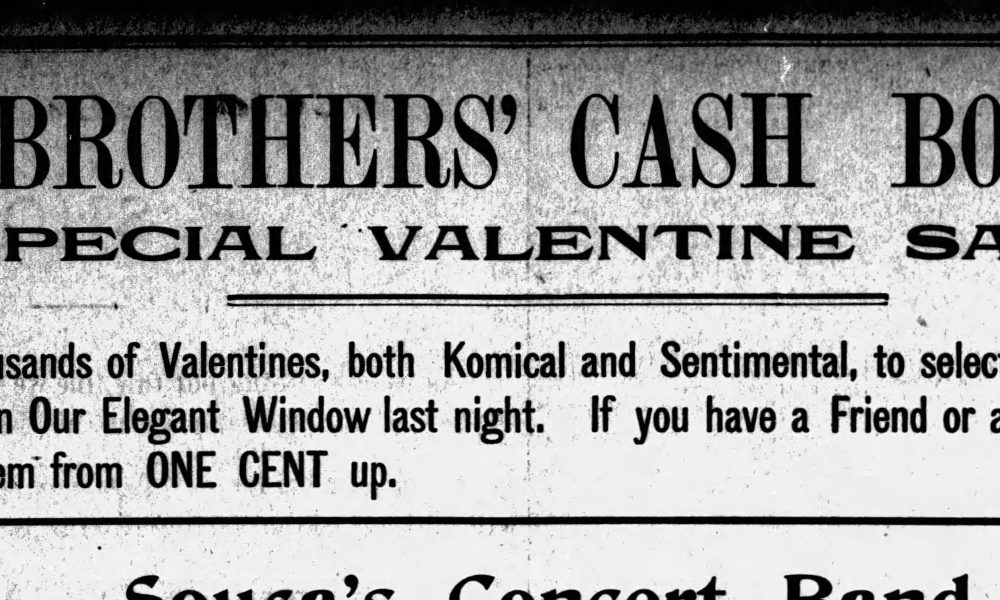

In 1896, Patton Brothers’ Bookstore in Salem advertised a Special Valentine Sale which offered both types of cards. They had sentimental valentines, and others that were known as comical or Penny Dreadful Vinegar Valentines.

Vinegar Valentines were sent anonymously, and as if receiving an insulting card wasn’t bad enough, in this time period, the receiver had to pay the postage. Some cards were just meant to be sarcastic or playful, but many were mean. An Oregon Statesman article published on Feb. 14, 1896, about this holiday’s history described how those drawn by Charles Howard, a well-known magazine artist of the time, drew caricatures of people within the intention of making the recipient mad.

In an 1895 article “Comic Valentines Have Antidotes” in The Kindergarten Magazine, a teacher relays the potential negative effects these comic valentines seemed to be having on children. This teacher encouraged children to focus on the beautiful images of the sentimental valentines, and only allowed them to share these in their valentine box at school.

Despite concerns by some, the trend of sending Vinegar Valentines continued through the early 20th Century in America. It is particularly interesting how these valentines were used during the women’s suffrage movement. There were mean-spirited cards attacking women fighting for their right to vote. But also, valentines supporting the cause.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association began its own Valentine postcard campaign in 1910, partly to raise awareness for their cause and to fight the Vinegar Valentines, but also as a fundraiser. They often used powerful patriotic symbols and logical arguments to make their case for the women’s right to vote. The 19th Amendment became law in 1920 and suffrage association became the League of Women Voters.

To learn more, please visit the wonderful online exhibit of Victorian era Valentines that is available online through the American Antiquarian Society: Victorian Valentines: Intimacy in the Industrial Age: https://www.americanantiquarian.org/valentinesephemera/victorian-valentines

This exhibit is the result of a collaborative student project between Smith College and the American Antiquarian Society.

This column is part of a regular feature from Salem Reporter to highlight local history in collaboration with area historians and historical organizations. Kimberli Fitzgerald, Salem’s historic preservation officer, writes about local history and city historic preservation efforts.

Kimberli Fitzgerald is the city of Salem's archeologist and historic preservation officer. She is a regular contributor to Salem Reporter's local history column.