Sometimes it pays to be average.

The Salem area economy is “average” – that is, no one private sector industry dominates employment. This characteristic helped Salem recover from pandemic job losses faster than other areas of the Willamette Valley.

What about economic success over longer periods of time?

Economic downturns in the Salem area have been less severe than they might have been in part due to the size and stability of state government employment.

But Salem’s mix of private sector industries, especially the diversity of its manufacturing, also helped the economy stay healthy in the longer term.

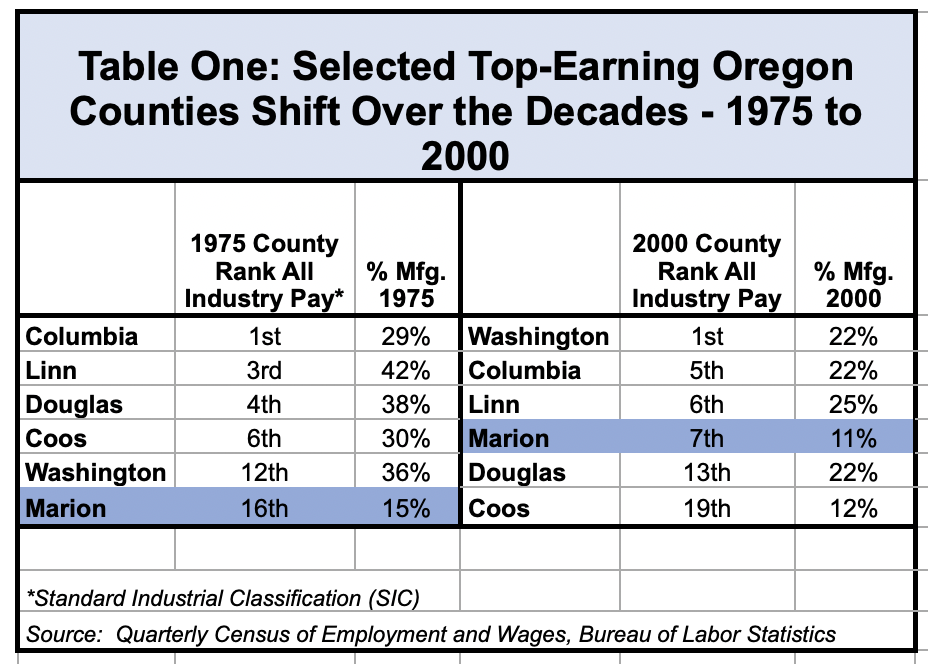

Looking back at the Marion County economy and other selected counties (out of Oregon’s 36 counties) in 1975, and then into the 2000s, will demonstrate this (see map). It will also provide a snapshot of the decline of manufacturing employment, and in particular, lumber and wood products manufacturing, an important factor in Oregon’s economic history.

The decline in manufacturing jobs has had an effect on wages, and workers earning good wages are, by any measure, a major component of a successful economy.

Which Oregon counties had the highest average all-industry wages in 1975? How did the economies of the top wage-earning counties evolve over the decades? And in particular, what part did manufacturing employment, especially lumber and wood products, play in this evolution?

One important note: the source of the following information, average annual all-industry wages (all wages divided by all jobs in one year) is an actual count of jobs.

Oregon employers report jobs and wages to the Oregon Employment Department every quarter, and this becomes the basis for determining unemployment insurance eligibility. Aptly, the compiled information is called the Quarterly Census of Wages and Employment. This measure is a nearly complete one – nearly, because self-employment is not included.

Now, back to 1975, when the timber industry was king and timber-related jobs paid good wages – four of the counties ranked tops in average all-industry wage were counties with a lot of timber-related manufacturing employment.

The highest average wage was in Columbia County, where nearly one of three jobs were in manufacturing, mostly lumber and wood products.

Linn County, third in average wages, was notable for several reasons. The county held the record for the largest portion of manufacturing employment of all 36 counties – four of 10 jobs were in manufacturing. Half of these were lumber and wood products, and another substantial portion was primary metals, an industry that has been a significant part of Linn County’s manufacturing employment to the present day.

Douglas and Coos counties, at wage positions four and six, had substantial manufacturing employment, and lumber and wood products jobs were the bulk of these in both counties.

In 1975, the Salem area, specifically Marion County, was a modest 16th in terms of wages. Its manufacturing industry was only 15% of all jobs.

But manufacturing employment was diverse. Although food manufacturing accounted for a substantial portion (43%), lumber and wood products was only 19% of manufacturing. Other sectors with substantial employment included paper, printing and publishing; fabricated metals; and industrial machinery.

Why was Washington County selected to be on the list? Although the county was largely agricultural land in 1975, with some 50,000 total jobs, manufacturing provided more than one of every three of these jobs. More than half were in instruments and related products, a harbinger of the future.

Let’s move ahead 25 years to the year 2000.

Marion County moved into 7th place in average wages.

Even though the county’s manufacturing employment had declined some, a number of categories had been added. These included apparel and textiles; chemicals and allied products; transportation equipment; and furniture and related products. Each new category added several hundred jobs to employment.

Columbia, Linn, Douglas and Coos counties all moved down the wage rankings as lumber and wood products employment declined. Coos County moved down the furthest, from 6th to 19th place.

Washington County took first place in wages in 2000. Half of its manufacturing jobs were electronics and electric equipment, and these jobs were paying the good wages Washington County high-tech manufacturing is known for today.

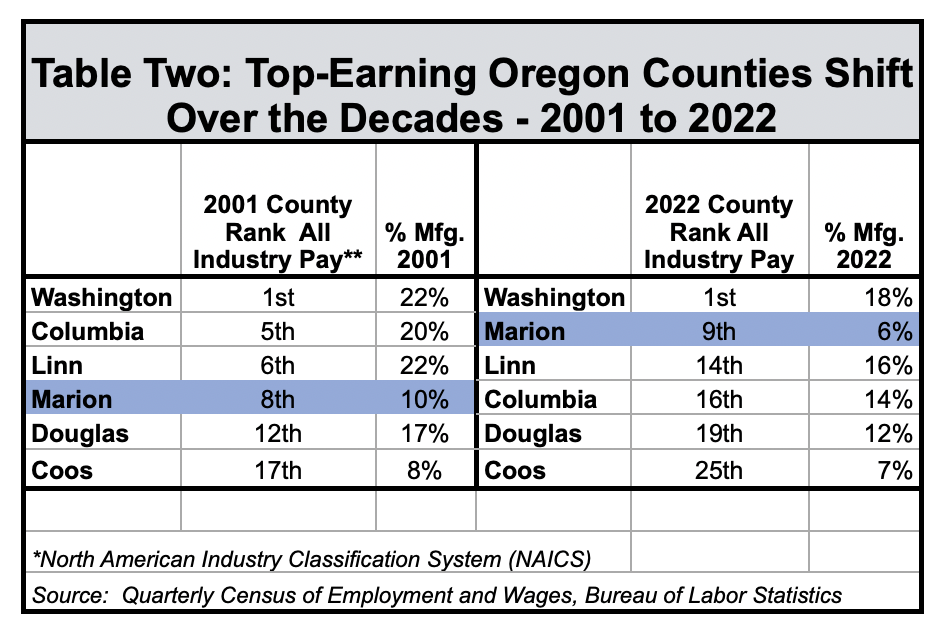

The next 21 years must be compared separately (from 2001 to 2022), because the way industries were defined was changed in 2001.

Despite the changes, the story is pretty much the same (see table two below). As lumber and wood products employment continued to decline, Linn, Columbia, Douglas and Coos counties moved further down the wage rankings.

Salem area’s manufacturing in 2022, although a smaller percentage of employment than previously, reflected the diversity that had developed over the decades (see pie chart below). This kept the Salem area’s wage ranking in a healthy 9th place.

A word about Salem’s food manufacturing – if there is any one product that could be said to “dominate” the area’s manufacturing over the years, it would be food. But the industry has adapted over the decades as consumer tastes have changed – fewer canneries, but more specialized items such as tortillas and potato chips.

Now let’s reinforce this story with one more look at wages.

How do average all-industry wages in the selected counties hold up to inflation from 1975 to 2022?

Here’s how:

- Washington County held first place for beating inflation by the largest percentage; wages in 2022 were 67% higher than in 1975;

- Marion County’s wages were a respectable 16% ahead of inflation;

- Linn, Douglas, Coos and Columbia counties’ wages lost ground to inflation; Columbia County lost the most – average wages were 25% behind 1975.

A brief explanation for all this: the decline of the timber economy in Oregon had to do in large part with the decline of the natural resource. Reasons for the decline in overall manufacturing employment over the decades, in Oregon and the U.S., are complex and include the impact of liberalized trade on global labor supply and gains in productivity through automation.

To sum up: The focus has been on those counties with a substantial timber-industry related base in 1975, compared to Marion County.

In the 1970s, manufacturing employment in Marion County was diverse, and lumber and wood products made up a relatively small portion of jobs. As manufacturing changed over the years, the industry became even more diversified. This helped avoid the dramatic economic downturns occurring in areas that had depended on lumber and wood products for prosperity.

Each Oregon region has its own economic story over the decades. If readers want to learn more about the economies of the various regions of the state, the Oregon Employment Department has an excellent resource. Each region has its own economist and workforce analyst, experts in their area. They can be contacted at https://www.qualityinfo.org/ – then Regional Info at the top of the information bar.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected].

STORY TIP OR IDEA? Send an email to Salem Reporter’s news team: [email protected].

SUPPORT OUR WORK – We depend on subscribers for resources to report on Salem with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Pamela Ferrara is a part-time research associate with the Willamette Workforce Partnership, the area’s local workforce board. Ferrara has worked in research at the Oregon Employment Department, earned a Master’s in Labor Economics, and speaks fluent Spanish.