As Salem’s police chief narrated a troubling rise in gun violence to a group of the city’s elected leaders, two men sitting in the audience exchanged a skeptical look.

The November joint meeting of the Salem City Council and Marion County Commissioners came after a landmark report commissioned by Salem police showed shootings in the city have doubled in the past five years, with the number of teenagers involved as shooters and victims doubling since 2021.

The issue wasn’t news to Levi Herrera-Lopez, executive director of Mano a Mano Family Center, or Eduardo Angulo, a founder of the Salem-Keizer Coalition for Equality.

Both men have worked decades to stem violence and strengthen communities in largely Latino areas in north and east Salem, pushing for investment in the neighborhoods bearing the brunt of the shootings.

“Let’s see what the solutions are going to be this time,” Angulo remembered thinking.

They’ve done their work while often fighting a public perception that Latino teenagers and families are a problem, or that mass incarceration and punishment will increase community safety.

Angulo lives adjacent to Northgate Park in a triangle of northeast Salem that’s been a hotspot for shootings. Herrera-Lopez lives outside city limits in east Salem.

Addressing the needs of their neighborhoods is work that is generally underfunded and often goes unrecognized until Salem’s leadership decides to pay attention.

“Those of us who have been doing this work, we don’t stop doing this work when the headlines stop,” Herrera-Lopez said.

Angulo said he’s glad to see city leaders discussing gun violence, but remains skeptical meaningful change will result.

“I’m waiting to see when they’re going to sit down and say OK, we’re going to create partnerships … with organizations that have served the community for years to start doing programs, gang prevention programs,” he said.

Echoes of the 1990s

Salem leaders declared gang violence a significant problem in the 1990s, responding to a wave of shootings that claimed the lives of five teenagers and saw strangers assaulted while out walking.

In 1998, the city recorded 59 gang-related shootings, the Los Angeles Times reported, double the number the previous year.

Neighborhood and nonprofit leaders say Salem’s response to the violence 30 years ago holds lessons for today.

Chief among them: solving the problem requires buy-in from families and teenagers in the most affected neighborhoods and community investment in the places they live.

Jim Seymour was leading the nonprofit Catholic Community Services at the time, and went to a conference about addressing gang violence. He said the experience led to a shift in how his organization worked on social issues, from viewing struggling families as a problem to viewing them as people with solutions.

“The police could go in and arrest people – the idea was sort of ‘chop the head off the snake’ – but the fact was the head just grew back as fast as they would chop,” he said. “The only place where gang suppression worked was where families came alongside with this determination to make the neighborhood a good place to raise their children.”

Concerns over gang violence sparked community meetings and the creation of new youth and family programs. The Salem Leadership Foundation formed, encouraging churches to be more active in communities and neighborhoods to tackle problems.

Local leaders including the mayor attended meetings led by young people, who spoke about what they needed to be successful, recalled Susann Kaltwasser, co-chair of the East Lancaster Neighborhood Association, who helped organize some meetings in her role as president of the League of Women Voters.

“We as adults sitting around listening to these kids learned a tremendous amount about how they see their world…what is helpful to them and what is not helpful,” she said.

The most effective programs came from collaboration between youth and adults who believed in them as partners, Kaltwasser said. Those included the HOME Resource Center for homeless kids, and other programs led by young people formerly in gangs.

Concerns over gang violence also led to a tough-on-crime crackdown that spurred a wave of Latino community organizing in Salem.

Angulo at the time was teaching, talking to teenagers in Salem, Woodburn and Portland, including in juvenile justice programs. Across cities and schools, Latino and Black teenagers spoke about being racially profiled, said they were assumed to be gang members and were disciplined or kicked out of school for minor infractions.

“These kids cannot be lying – all of them from Portland to Woodburn to Salem,” he remembered thinking.

With his wife Annalivia, he founded the Salem-Keizer Coalition for Equality, a Latino parent group that got parents more engaged in their kids’ education while pushing local schools to do a better job teaching Spanish-speaking kids and immigrant families.

Holding schools accountable for teaching kids to read is gang prevention, he said. Kids who are behind their peers in school are likely to become disengaged and act out in class, disrupting learning for others.

Herrera-Lopez got involved as a founding member of Latinos Unidos Siempre, a youth organization that fought both gang influence and racial profiling while giving teenagers a place to go after school.

He and Kaltwasser were among local leaders who pushed back when an administrator with the Salem-Keizer School District created a “gang manual” which purported to identify signs teens were involved in criminal activity. In reality, Herrera-Lopez said, many were innocuous Mexican cultural symbols.

“Everyone was treated as a potential criminal, not as a potential successful kid that’s going to graduate,” Herrera-Lopez said.

Root causes

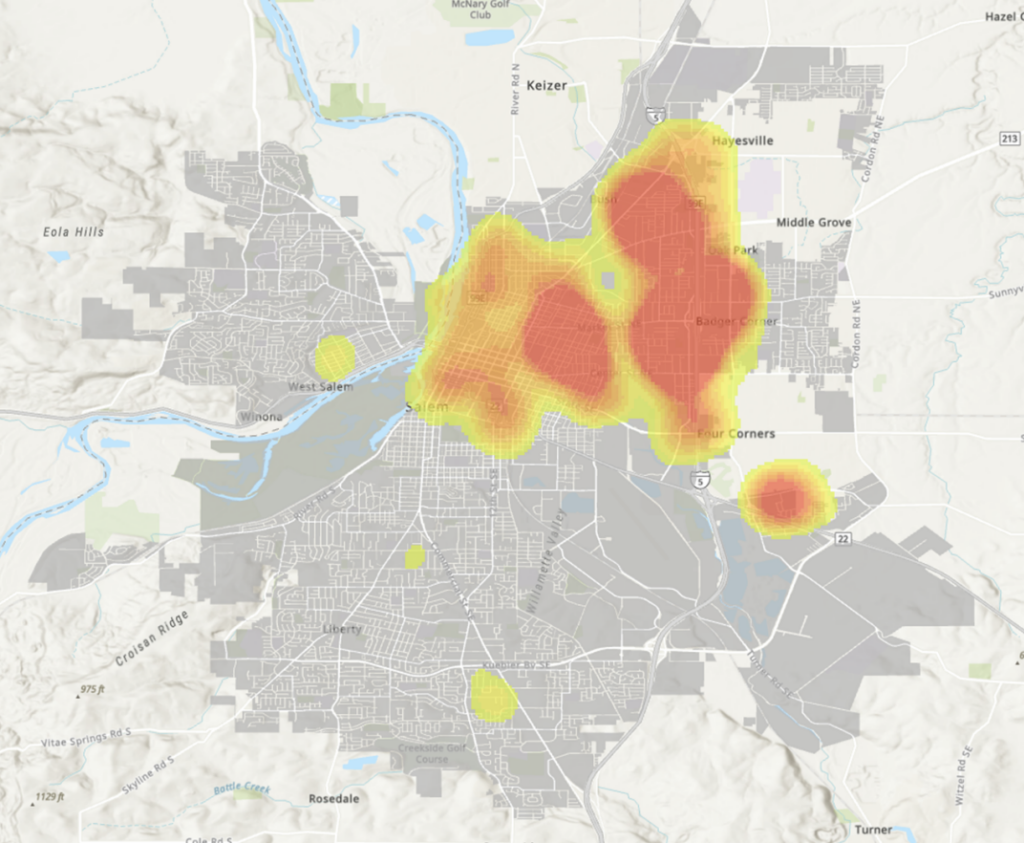

The 2023 police report presented a sobering picture of violence that’s unevenly distributed across Salem.

Last year, the city saw 20 shootings concentrated in northeast Salem, particularly the Northgate neighborhood bordered by Portland Road, Silverton Road and Interstate 5, and the north Lancaster area. Those numbers don’t include shootings outside city limits, like the Four Corners area in east Salem where Herrera-Lopez lives. They don’t include episodes where no one was injured.

Researchers pointed to the influence of gangs as one factor driving the violence. Of the shootings researchers analyzed in the past five years, about half involved someone affiliated with a gang as a suspect, victim or both.

Jose Gonzalez, the city councilor representing northeast Salem, sees the violence as a community issue that his neighborhood bears the brunt of.

“Gun violence is like the fever you get after not taking care of yourself,” he said.

Salem is the first significant city on Interstate 5 north of California with a large Latino population, he said, a territory ripe for gang-related drug trafficking.

His children, now adults, attended several high schools in Salem as the family moved around the city. He said his sons reported drug use was highest by far at West Salem High School, the most affluent school in the district.

Gangs, he said, “use the poor youth, the Latino youth, to sell to the rich white kids.”

Herrera-Lopez said gun violence and teenagers susceptible to gang influence are real problems.

But he sees the report as a call for more money for police. He said law enforcement isn’t equipped to solve the root causes of violence or teenagers engaging in antisocial behavior.

“Gang involvement is, for most youth, a symptom of something else that’s happening,” he said. “They’re disconnected … the person who comes along and embraces them is gonna win their heart and mind, basically. And if that happens to be a group that’s engaged in antisocial activities, then that’s who they’re gonna go with.”

He questioned some of the report’s conclusions, like how researchers determined whether shooters or victims were involved with gangs. He’s skeptical of law enforcement assessments of gang involvement given the broad brushes used to paint teenagers in the 1990s, he said.

“If you had any kind of connection to someone who said they were in the gang that made you a gang affiliate, and that made whatever you did a gang-involved incident,” he said. “As a community, I think we would do a lot better if we start with saying, how do we address gun violence in our community, regardless of who’s pulling the trigger?”

Looking at how teenagers access guns is one solution, he said.

The report also said many of the shootings that involved gang members were personal disputes – fights over romantic partners, for instance, rather than gang-related issues over drugs or criminal activity.

“The violence doesn’t seem to be so much about gangs locking horns as individual gang members having a difficult time resolving conflict, and I actually think that’s probably a good thing. I think that’ll be easier to resolve,” Seymour said.

Disinvestment

Teenage isolation and disconnection from school during pandemic school closures has contributed to gang influence in Salem, according to the report – a point school counselors, educators and nonprofit leaders agreed with.

It’s a problem Herrera-Lopez said his employees see. Mano a Mano has three “promotores” – mentors, case managers and cheerleaders working directly with struggling young people who are generally involved in the juvenile justice system.

The work is time-intensive, and they work with about 25 young people at a time. Since the pandemic, he said they’ve seen a huge increase in need as teens developed mental health problems from isolation and trauma.

Kids in their program do well, he said. Those who stay involved for at least a year generally go on to meet their goals and graduate high school. They’re hoping to expand soon with a state grant, but the need far outstrips their resources.

“You have to be available for the families. For as long as they need you … and that’s a model that our system is really not set up for,” he said. “We’re lucky we get like two- or three-year grants, but we really need to be available at the latest from the moment they go into middle school until they graduate.”

The neighborhoods kids grow up is a factor in how they see themselves and their city, he said.

He illustrated his point recently, walking along Northeast Sunnyview Road toward Lancaster Drive. It’s a major street bordering one of the northeast Salem neighborhoods where police have recorded more shootings than anywhere else in Salem.

There are no sidewalks, and almost no crosswalks across the busy road despite several large apartment complexes nearby. Many of the low-income families in the neighborhood have no choice but to walk, sometimes with strollers, to get to grocery stores on Lancaster. Herrera-Lopez recalled it took a child being hit and killed by a utility truck nearby on Northeast Hawthorne Avenue, years ago, for the city to put in a crosswalk at the intersection.

A house along the street has a gang tag spray painted on the fence: “LSK”, or Loco Sureño killer.

Such graffiti is common in many parts of north and east Salem. A persistent complaint from neighborhood leaders and families is that police and city officials are slow to respond and clean up tags, giving the relatively small number of Salemites involved in gangs the sense that they control the neighborhood.

“If people don’t care about the place they’re living in and the city doesn’t care to fix it up, why should they care?” Herrera-Lopez said.

Kids growing up in neighborhoods lacking basic features will easily believe that they aren’t worth investing in. Herrera-Lopez said walkable neighborhoods, green spaces and street lighting aren’t luxuries — they should be part of every neighborhood, regardless of income.

“If we don’t address that, then we’re creating an environment where more users are likely to get involved in gangs because they’re living in bad neighborhoods that we’ve created,” he said, referring to the city and county. “Why can’t the neighborhoods in east Salem look like the neighborhoods in south Salem?

In northeast Salem, Angulo and Seymour have been working for several years on a long-term effort to strengthen neighborhoods, convening neighborhood moms to talk about issues, plan events and organize their neighborhoods.

The program has resulted in efforts like Fun Fridays at Northgate Park, which brings families to the park and improves safety by building connections among residents and with police.

The Hallman Neighborhood Family Council successfully lobbied Gonzalez to include a new park bathroom in a bond measure that voters approved in 2022.

But Angulo said Salem is lacking programs targeted at teenagers who are disengaged and searching for a place they feel they belong and where their culture is celebrated.

“These kids are in pain. Many of these kids are angry,” he said.

They need places to go, like community centers in their neighborhoods, and a community willing to pay for programs to connect them with mentors and other help.

When Salem city councilors met to discuss the gun violence problem, Gonzalez was the sole leader who cautioned that community organizations were already stretched thin and would need investment to make meaningful change.

Like others in north and east Salem, he said he hopes there’s an appetite to address the violence. But doing so will take a sustained commitment, he said, not just a few meetings.

“It’d have to be a multi-year big effort, if there really was genuine interest in solving this problem,” he said. “That’s my concern: there really isn’t interest to solve it.”

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

SUPPORT OUR WORK – We depend on subscribers for resources to report on Salem with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.