Salem city leaders can’t say how many workers would be subject to a tax on wages going before voters in November, acknowledging their assurances to the community of what the tax could fund are only an estimate.

A Salem Reporter analysis of the city’s revenue model found city officials counted money from remote workers who in fact wouldn’t be taxed. They also added in new money from the payroll for businesses based outside city limits.

The state of Oregon, by far Salem’s largest employer, has over 11,000 people on payroll who are assigned to a Salem office but work elsewhere some or all of the time, according to the state Department of Administrative Services. About 4,200 of them are fully remote. Another 7,100 are hybrid, working only part-time in Salem.

Their wages are factored into city estimates for tax collection, but those workers wouldn’t actually pay tax unless they physically work in Salem.

Josh Eggleston, Salem’s chief financial officer and the main architect of the tax model, said in an interview with Salem Reporter he expects those overestimates of tax collected to be offset by underestimates in other areas.

For example, the city’s model doesn’t include wages for self-employed Salemites, who would pay the tax, or people working within the city for employers based outside of Salem.

His model also reduces by 20% the total forecasted tax collection to account both for overestimates and for people subject to the tax who don’t pay it.

“It’s always been a projection so it’s not going to be right. It’s going to be high or it’s going to be low. But it’s the best information we have right now,” Eggleston said of the model.

The accuracy of the city’s forecasts is a key question as proponents of the tax have cast it as the last hope to save Salem from drastic budget cuts that could shutter the West Salem library, cut police officers focused on drug enforcement, and turn off splash pads in city parks.

If Salem voters give the city a thumbs-up for the tax, city officials say they’ll preserve existing city jobs while hiring a dozen police officers, 14 firefighters and keeping open several homeless shelters.

Those plans, presented to the Salem City Council in April, assume the tax will bring in $27.85 million in the first year — an estimate based on 2022 state wage data for the Salem area.

But city leaders said that number is a best guess, because there’s no local or state data to identify who’s actually subject to the tax.

That’s common for new taxes, particularly payroll taxes, said Richard Auxier, a researcher with the Tax Policy Center of Washington D.C., who reviewed the city of Salem’s revenue projections and calculations at the request of Salem Reporter.

“Even if you use the right dataset and you make all the right assumptions, it’s still just an estimate. You don’t know,” he said. “Any time you did not have a tax one year and you have a tax the next year, that first year is inherently unpredictable.”

In his home of Washington D.C., city officials implemented a payroll tax in 2020 to fund a family leave program, then slashed the tax rate in 2022 while expanding benefits after finding the program cost less to administer.

“It’s not that anyone messed up. It’s just that it’s impossible to know,” Auxier said. In Salem, “because this is meant to save the budget, you’re kind of under more pressure” to get estimates right.

He said the issue of who’s subject to taxes, particularly on wages, has become more complicated as more people work remotely, and Salem isn’t alone in simplifying tax estimates that come up against the question of remote work.

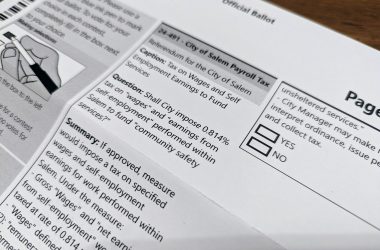

If it’s implemented, Salem’s payroll tax would take 0.814% of workers’ paychecks for anyone working within city limits, regardless of where their employer is based. Minimum wage earners are exempt.

Remote workers assigned to a Salem office, including many state employees, wouldn’t pay the tax unless they’re physically working within Salem city limits. Meanwhile, Salemites working from home for employers based in other cities or states would have to pay the tax.

Eggleston said he estimated how much tax would be collected using data from the state Department of Revenue. He calculated tax earnings as a percentage of total 2022 reported payroll for the Salem area. But that state figure includes the wages paid by any business with a Salem address.

That data doesn’t split out businesses who are based outside city limits but have a Salem address — such as those located in the unincorporated part of Salem east of Lancaster Drive and south of Center Street.

“We don’t have a mechanism that could really delve that deep. We don’t have a business registry or business license. The state doesn’t really track it at that level,” Eggleston said.

Eggleston said he never sought to establish the number of state workers working remotely, though he asked the Department of Revenue in March via email if the data they provided included a discount for remote workers.

“I would say there could be a 5% reduction to account for the state workers … who don’t live in Salem or commute but (occasionally),” wrote Kelvin Adkins-Heljeson, an analyst for the revenue department, in response. “On the other end there are people who commute into Salem or who work for organizations based outside Oregon or Salem. I believe it’s probably a fair representation overall.”

The city sought an analysis from consulting firm Moss Adams to validate its revenue model for the payroll tax. Two consultants reported to councilors in February that the revenue projections were good.

“It is based upon solid data provided by the Oregon Department of Revenue. The calculations are logical and sound,” said consultant Tommy Conkling.

The city paid Moss Adams $45,000 for that validation and work comparing Salem’s budget deficits and staffing levels to other Oregon cities. Courtney Knox Busch, the city’s strategic initiatives manager, said Moss Adams has not provided city officials a more detailed analysis of the revenue model beyond the February presentation.

“Moss Adams’ response was that Salem’s 20% assumption of under-collection could account for remote workers. However, without moving into the rule-making phase, we don’t know and can’t be more specific about the impact of remote work on collection. There has not been further discussion or direction about these details,” Knox Busch said in an email.

The city council in July narrowly approved the tax 5-4 before a campaign led by Oregon Business & Industry gathered enough signatures to refer the tax to Salem voters in November.

Public testimony and in writing before the council vote was overwhelmingly opposed to the tax, with some employers and others saying the tax would be overly complicated and difficult to administer.

If voters approve the tax, the city wouldn’t hire any employees it’s intended to pay for until tax revenue is collected, according to City Manager Keith Stahley.

The state data shows a total payroll of about $5.5 billion for Salem businesses in 2022. The state Department of Revenue collected the data to implement the statewide transit tax, which rolled out in 2018.

Eggleston said he had several conversations with revenue employees about the city’s proposed tax and the state’s experience implementing a payroll tax, but did not seek formal written advice or an opinion.

In response to questions about what revenue department employees told city leaders about the soundness of their methodology, department spokesman Rudy Owens wrote, “DOR does not have the data necessary to accurately estimate the tax base for the proposed city of Salem tax. The idea to use wages from employers with Salem zip codes is the only estimate or proxy that DOR can provide. DOR has no way of knowing the accuracy of this method.”

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

SUPPORT OUR WORK – We depend on subscribers for resources to report on Salem with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.