Forty miniature homes line a shaded parking lot off Portland Road in northeast Salem. The shelters have colorfully painted doors sporting bumblebees, bright flowers, and peacock feathers. Outside, a dozen kids run back and forth under a sprinkler on their push scooters and line up for ice cream while their parents chat at a picnic table.

The micro shelter village for families, run by Salem nonprofit Church at the Park, is one of two city-funded sites that have operated in Salem for about two years, providing hundreds of adults and families temporary shelter.

Data obtained by Salem Reporter shows that over the past year, the shelters sent 82% of families and 56% of adults to better destinations, which could include permanent housing, transitional housing, inpatient treatment, detox or other care facilities.

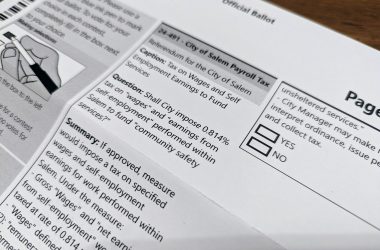

Yet the future of Salem’s micro shelters is up in the air as they only have funding through June 30, 2024. A new city wage tax, intended to fund their continued operations, will head to voters in November after thousands of Salemites signed a petition to refer the measure to the ballot.

If the shelters were to close, “I think about the ripple effect that would happen with the loss of 212 beds and the staff who have worked hard to build relationships,” said Gretchen Bennett, the city’s homelessness liaison.

Church at the Park leaders said they’re now looking at other funding options.

The tax is expected to bring in $27.9 million per year for police, fire and homeless services. According to the staff report $7.9 million would be split between the navigation center and the three micro shelters.

These programs are currently funded with state grants and federal Covid relief money. The city otherwise does not have money in place to keep those services running beyond 2025.

Village of Hope was the first micro shelter village Church at the Park established for adults ages 18 to 65 in April 2021, followed by the northeast Salem site for families. A new young adult village for ages 18 to 24 is set to open by the end of August on Southeast Turner Road.

Micro shelter villages are managed temporary housing for unsheltered people, combined with case management and outreach services to help people with needs like permanent housing or health care. Each site has around 40 to 60 pods that are 64 to 72 square feet, wired with electricity and a heating unit that can fit two single beds or bunk beds. Portable toilets and sinks are available in a common area outside.

Mayor Chris Hoy sees the shelters as a key part of the city’s homelessness response and said he’s encouraged by their recent growth and success rates.

Salem leaders in 2017 started a rental assistance program to subsidize getting homeless people into apartments and quickly learned “it’s really difficult to take somebody out of a tent and put them in an apartment and have them be successful,” said Hoy. “They really need help before that.”

Over the past year, the family site on Northeast Portland Road served 295 people from 99 households, with an average stay of six months.

Of those, 191 people moved out of the shelters — one in three to permanent housing, according to data shared by Matt Herbert, Church at the Park’s navigation services and data director.

A total of 82% went on to “positive destinations,” which include permanent housing, transitional housing, detox, treatment, and other care facilities.

During the same timeframe, the Village of Hope adult site at 1280 Center Street N.E., served 206 people and saw 155 move out. The site has a current waitlist of 760 people.

Of those who moved out, 23% left for permanent destinations and 56% to positive destinations, with an average stay of nine months.

“As a baseline, we’re happy with the numbers,” said Herbert, although “we are always aiming for an increase to permanent destinations and positive destinations.”

The data provides an extended look at the effectiveness of one of Salem’s newer programs intended to get homeless people off the streets. Last May, Church at the Park reported similar rates of success for Village of Hope after the site’s first year of operation.

Church at the Park’s rates are slightly below the average for 10 Portland sites, where on average around half the people leave for permanent destinations, said Denis Theriault, deputy communications director for Multnomah County. The county oversees many of the Portland village-style shelters which house anywhere from 10 to 150 people, similar to Salem’s micro shelters.

Theriault guessed that this gap could be due to differences in funding, length of being open, or shelter size, as Portland has mostly smaller sites.

Gretchen Bennet, Salem’s homelessness liaison, said the sites have done a great job getting people to positive destinations, “which is very good for this group of people with the challenges that they have and the lack of affordable housing.”

Church at the Park operates its three programs under yearly contracts with the city of Salem. The city allocated $2.1 million in state sheltering funds to operate Village of Hope from June 2023 through the end of June 2024. During that same time period, the city allocated $2.6 million to the family micro shelter site, and another $260,000 for Church at the Park’s Safe Park program, which finds places people living in vehicles can stay overnight.

Under the contract, Salem requires monthly reports from all the sites including both financial data and exits to positive destinations. The contract allows the city to perform an audit to ensure that spending is consistent with the grant agreement. The city hasn’t set any benchmarks or expectations for exits to positive or permanent destinations in the contract.

“We wanted first to gain information to determine a baseline of data from which we can set a target,” wrote Bennett in an email to Salem Reporter.

The city is currently working on a performance audit of all the homeless services they fund, to make sure expectations are being met, said Hoy.

Sam Dompier, Church at the Park’s chief development officer, said that between the 212 beds at the family and adult sites the cost per bed per month averages to $1,850, an $250 increase from last year. Dompier said additional medical benefits for employees, annual cost of living increases and overall inflation, especially with food expenses have contributed to the increase.

Church at the Park has also recorded a reduction in 911 calls and emergency room visits by people staying at micro shelter sites. They work to measure the impact of shelter and housing on emergency system utilization by tracking ER use and 911 calls. Residents are surveyed when they enter the micro shelters about their use of emergency services in the last six months. Six months later, they do a follow-up survey and compare the results.

Across Church at the Park programs for the 2022-23 fiscal year, those surveys showed about an 80% reduction in the use of the emergency room and a 75% reduction in calls to 911.

Herbert said that teaching people which symptoms elicit what type of medical response or treatment, getting people connected with primary care, and providing a safe place to stay can all help with the reduction of emergency service use.

Salem has double the national average rate of chronic homelessness for adults without children which is 62% for the region, versus 34% in Oregon and 27% nationwide, according to the Mid-Willamette Valley Homeless Alliance 2022 Gap Analysis.

During the region’s annual homeless count in January 2023, they identified 878 people without shelter in Marion and Polk counties. The annual count is widely regarded as an undercount among service providers.

The micro shelters are low barrier, allowing guests to bring pets. Sobriety isn’t mandatory. However, people living there are expected to follow rules and agree to community guidelines, including a curfew, quiet hours, and cooperating with case managers for a transition plan.

“I think they fill a unique role for people who maybe have severe claustrophobia or trauma that happened in an indoor space,” said Bennett.

The small units allow quick access to step outside and people who have experienced chronic homelessness appreciate a micro shelter versus a large building, said Bennett. They have also allowed her to offer more diverse options when it comes to working with people to get sheltered.

The family micro shelter site, along with Family Promise and St. Francis Shelter, are the only shelters in Salem that will house adult couples with children together. Bennet said there are more families still looking for shelter, so losing that site would be detrimental.

Right now the family site is working to expand its space by 30 beds to house families with more than four kids. They are currently working to install showers and bathrooms to keep the shelter up to code and hope to have that open before the winter of 2023.

Herbert said that looking forward they are excited to grow their community care program that started in January 2023 and will follow people up to six months after they have secured housing.

Church at the Park is also close to opening a long-delayed young adult micro shelter site that would house ages 18 to 24. That site will have a commercial kitchen so residents can train to help them get restaurant jobs, Herbert said.

To sustain funding if the city of Salem can’t renew contracts, Church at the Park leaders are looking into partnerships with counties, Herbert said. They also have a new agreement with PacificSource that will help pay for peer support and other services.

Church at the Park is continuing to work with the city to figure out alternative long-term funding options past June 2024, when they run out of money.

“I would hate to lose that spot that gives people options when it comes to sheltering,” said Bennett.

Contact reporter Natalie Sharp: [email protected] or 503-522-6493.

SUPPORT OUR WORK – We depend on subscribers for resources to report on Salem with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Natalie Sharp is an Oregon State University student working as a reporter for Salem Reporter in summer 2023. She is part of the Snowden internship program at the University of Oregon's School of Communication and Journalism.