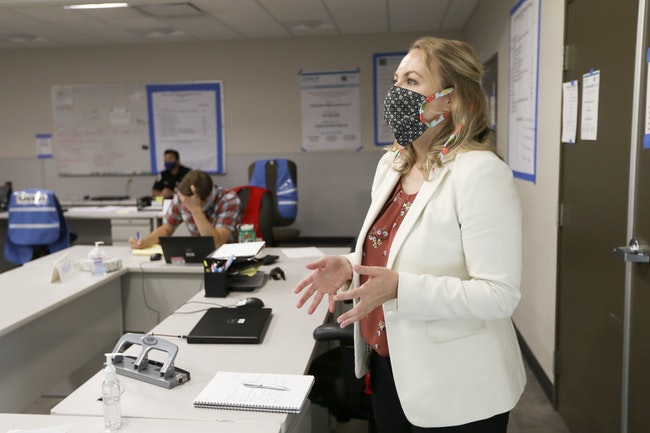

Katrina Rothenberger, stands in the COVID-19 incident command at the Marion County Health and Human Services office on Monday, July 13, 2020. (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

When Katrina Rothenberger got the call that Marion County had recorded its first Covid infection, she was celebrating her father’s birthday on a Saturday night.

Rothenberger, Marion County’s public health division director, was asked to appear in a press conference the following day with Gov. Kate Brown.

“I tried to shake the governor’s hand. She gave me an elbow bump instead,” Rothenberger recalled of the March 8, 2020 announcement – the first publicly confirmed case of the virus locally.

Rothenberger spoke Friday with Jacqui Umstead, Polk County’s public health administrator, and Cheryl Nester Wolfe, Salem Health CEO, at Salem City Club, reflecting on nearly two years of public health work during a pandemic.

Rothenberger recalled how nobody wore masks as health officials gathered in Portland in early March to announce seven new cases of Covid in Oregon.

“2020 does feel like a lifetime ago,” Rothenberger said.

Marion County had just thrown away masks and other protective equipment that was several years expired and initially intended to help during the swine flu pandemic of 2009. Now, she said, “I will never throw out an expired mask again unless it’s contaminated.”

Both public health leaders said they needed to quickly scale up staffing to meet the demands of notifying everyone infected with the virus and trying to trace its spread.

“It wasn’t new or novel to do this type of work for public health, but the sheer volume of cases and the kind of support you need to do it well was a challenge,” Umstead said.

The Covid response quickly consumed the bulk of public health resources. Rothenberger said initially, the department hired temporary workers to help trace cases because they were unsure when extra money would run out. As it became clear the pandemic would last longer than a few months and funding continued, they were able to make some positions permanent.

To date, she said Marion County has spent $17 million on Covid response, about $30,000 per day.

“Other important public health work has stopped. And that is something that I’m pretty concerned about,” Rothenberger said.

As they responded to Covid, Umstead said Polk County also scaled back other public health programs.

“We basically went from operating a reproductive health program, an immunization program, a home visiting program, full time, to offering it rarely, like one day a week, because we had to take all of our resources essentially and put them into Covid,” Umstead said.

Translation and disseminating accurate information to the public was a challenge early on, Rothenberger said. The county quickly realized it didn’t have enough translators to ensure all county residents were receiving timely information about the pandemic. Partnerships with community organizations played an important role in reaching people and helping spread the word about public health measures, testing events, and later vaccination clinics.

Public health leaders struggled too as scientists learned more about the virus and recommendations shifted, particularly around masking.

At Salem Health, Wolfe said the pandemic has highlighted a longstanding issue in Oregon: few available hospital beds.

“We have in Oregon the lowest count of hospital beds per capita in the nation … and we have certainly needed every one of those,” she said.

The hospital is building a new tower which is expected to open to patients next summer. Wolfe said the pandemic moved up Salem Health’s timeline for their next new hospital building from a decade in the future to seven or eight years.

The number of Covid patients in the hospital has declined in recent weeks, but Wolfe said Salem Hospital is still seeing most or all of its beds full. Covid patients coming into the hospital are about 90% unvaccinated, she said.

Umstead said her office has gotten pushback against vaccination and disabled comments on their Facebook page because people were routinely posting false information about the pandemic and vaccines.

“When we’re doing case investigations, you know, there’s definitely been people who just don’t believe in Covid don’t believe in the vaccine, they just flat out refuse and, and those conversations tend to end quickly, because there’s not usually a lot you can do to change somebody’s mind at that point,” Umstead said.

In response to a question about the impact of anti-vaccination sentiment on the department’s work, Rothenberger said hasn’t received harassment or threats, something other public health workers across the U.S. have reported.

She then said organizations administering vaccines are reporting people reluctant to go to a vaccination event feel less stigma if they’re attending an event billed as Covid testing where shots are also available.

“If there’s a testing event that might be less risky. It’s also an opportunity to provide more education,” she said.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!