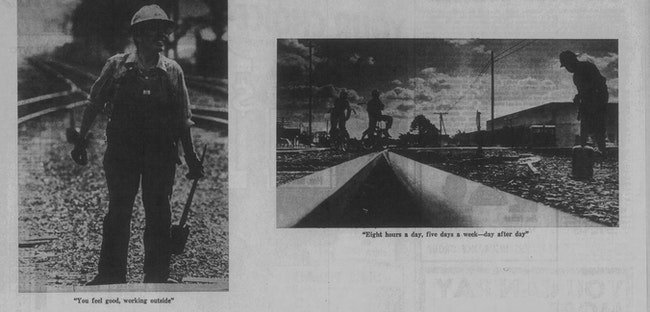

A photo essay published in the Capital Journal on Oct. 12, 1970 detailed Jose Marcos Campos’ railway work, shortly before his retirement.

For over a year now I have had ‘exploring Salem’s Hispanic Heritage’ on my list of things I want to do. September 15th was the start of National Hispanic Heritage month so I decided to move this to the top of my list.

National Hispanic Heritage was recognized by President Lynden B. Johnson in 1968 when he established Hispanic Heritage Week. This week in September was consciously chosen to coincide with Independence Day celebrations in several Latin American countries. Five nations in Central America declared independence from Spain on Sept. 15, 1821: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. Mexico declared its independence from Spain on Sept.16, 1810 and Chile declared independence on Sept. 18, 1810. Belize declared its independence from Britain on Sept. 21, 1981.

In 1988, Congress expanded this celebration to a month-long event from September 15 through October 15th in order to allow for more activities and events to celebrate Hispanic Culture and achievement. One of my colleagues who knew that I was interested in exploring this topic recently let me know that they had found a great photo about a really interesting gentleman named Jose Marcos Campos.

A photo essay published in the Capital Journal on Oct. 12, 1970 detailed Jose Marcos Campos’ railway work, shortly before his retirement.

A photo essay published in the Capital Journal on Oct. 12, 1970 detailed Jose Marcos Campos’ railway work, shortly before his retirement.

Jose Marcos Campos was born in Penjamo, Mexico and came to Salem in 1921. He worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad for 50 years. The Capital Journal published a full page of photos of Jose right before his retirement on Oct. 12, 1970 called “A Set of Rails, A Way of Life”. This story documented his work as a “traquero” or railway worker. In 1965, Jose and his wife were pictured in the Dec. 21, 1965 Statesman as part of a group of new American citizens sworn in at naturalization ceremonies in Marion County Circuit Court.

Jose and his family lived on Leslie Street where his wife raised their family and where his wife Nona Novarro’s family had lived since 1940. The 1940 United States Federal Census lists the Navarro household located at 1394 Leslie Street S.E. I was excited to discover this this house is listed on the State of Oregon Inventory of Historic Properties as the “John L. Schofield House” (c.1890), recorded by Paul Hehn in 1981.

Interestingly, Hehn notes that the property was owned by Silbarrio Nabarro in 1942, but he was unable to find information on this family (possibly due to the misspelling of his name). Silberio D. Navarro and his wife Mareia later lived at 930 14th St. S.E. until Silberio’s death in 1960.

1394 Leslie Street S.E., the former home of Jose Marcos Campos and his family, is on the Oregon Inventory of Historic Properties as the “John L. Schofield House” (Courtesy/City of Salem)

1394 Leslie Street S.E., the former home of Jose Marcos Campos and his family, is on the Oregon Inventory of Historic Properties as the “John L. Schofield House” (Courtesy/City of Salem)

I find it very interesting that the railroad moved to hire Latinos during the Chinese Exclusionary period through the early 20th Century, which is when Jose Marcos Campos began working for Southern Pacific Railroad. In 2012 Jeffrey Marcos Garcilazo wrote Traqueros Mexican Railroad Workers in the United States, 1870-1930 (Al Filo: Mexican American Studies Series). Garcilazo documents the discrimination and racism Hispanic rail workers experienced as well as the community life and traquero culture.

Another interesting aspect of Salem’s Hispanic history that has yet to be fully explored is the local impact of the Bracero Program. From 1942 to 1964 the United States coordinated with the Mexican government to bring millions of Mexican men to the United States to work on local farms.

In a 1942 Capital Journal article “Farm Workers Key Problem for Gardens” the Polk County War Board Chairman, R.D. Pence, announced Oregon’s “Plant and Plan for Victory” where it was clear that many of Oregon’s 1942 war food goals depended upon cooperation between growers, migrant workers and the public to prevent serious food shortages. Hispanic workers were also brought in to assist at lumber camps and hops harvests.

Migrant workers continued to provide support to local farmers even after the end of World War II and through the Korean War. After the start of the Cold War in 1953, the federal government kept the Bracero program in place, and some farmers and church organizations were working to provide support for local migrant workers in the Salem area.

Jose Marcos Campos (back row, fifth from left) was among the immigrants who became naturalized U.S. citizens during a 1965 Marion County Circuit Court ceremony.

In 1956 the Statesman Journal reported on the work of the Salem Council of Churches plans for a migrant ministry in their August 4, 1956 article “Church Council Lays Plans for Fall, Winter Program”. In addition to stressing the importance of providing support to Hispanic migrant workers during the fall and winter months, the Salem Council of Churches recognized the Hardman “Sunset” Ranch for construction of a new recreation building for their migrant workers.

While migrant workers clearly filled a serious gap during the forties and even into the late fifties, by the late 1950s some local farmers and lumber firms asked the Oregon Legislature to find a solution to what they had named “the migrant problem.” Dr. Donald Palmer, the research director for the 1959 Legislative Interim Committee on Migrant Labor led the Oregon Conference of Migrant Labor on December 15, 1960 in Salem where delegates met to address issues brought up on both sides.

Ultimately the federal government officially ended the Bracero program in 1962 primarily because farmers presented economic evidence that migrant workers reduced the wages of US farm workers, and that the initial need that warranted the establishment of this 1942 program was no longer warranted. To see the Braceros in Oregon Photograph Collection, click here. There is also a wonderful Oregon Public Broadcasting video: Oregon Experience- The Braceros that you can view here:

To learn more about the Bracero Program from a national perspective visit http://braceroarchive.org/about.

Editor’s note: This column is part of a regular feature from Salem Reporter to highlight local history in collaboration with area historians and historical organizations. If you have any feedback or would like to participate, please contact managing editor Rachel Alexander at [email protected].

NEWS TIP? Send your story idea, information or suggestion by email to [email protected].