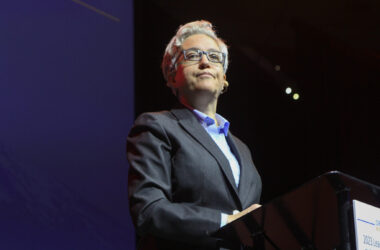

Florinda Velasquez, 74, prepares to receive her second dose of Covid vaccine from medical assistant Ana Barcenas at Lancaster Family Health Center in southeast Salem on Thursday, March 4. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

It was just before 4 p.m. on a recent afternoon and the parking lot at the Lancaster Family Health Center was nearly full.

Inside, Florinda Velasquez, 74, was among dozens of people cycling through the clinic’s daily vaccination drive, staffed by bilingual nurses and medical assistants.

“With the first one, I didn’t feel anything. With this one, who knows?” Velasquez said, speaking in Spanish.

The health center in southeast Salem is one of two in Marion County run by the Washington-based Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinic, which operates community health centers in areas with little access to medical care, with a particular focus on migrant and seasonal farm workers.

Clinics like this are a key part of Oregon’s plan to make vaccination more accessible to communities hit hardest by Covid.

Latinos account for 26% of all cases in Oregon despite making up just 14% of the state’s population. Farm, agricultural, manufacturing and food processing workers and their family members have been particularly impacted, and workers in those sectors are disproportionately Latino. Yet in most cases, they’re still not eligible for a vaccine.

Despite a statewide goal to center equity in the vaccine rollout process, just 4% of the 740,000 Oregonians who have gotten a shot to date are Latino, according to Oregon Health Authority data. Marion County has fared better, with about 10% of vaccines going to Latinos, who make up 27% of the county’s population. That’s about 5,900 Latinos out of 59,500 Marion County residents who have gotten at least one shot.

Starting this week, the Oregon Health Authority is allowing seven health centers around Oregon to begin vaccinating any of their patients 16 and older as part of a pilot program. The centers receive federal funding for providing medical care in underserved areas and take patients regardless of insurance or ability to pay.

Those participating include the Lancaster clinic and Salud Medical Center in Woodburn, both of which serve predominantly Latino patients. Together, the two have been vaccinating about 1,600 people weekly said Amanda Hill, who directs the Lancaster clinic.

The change is intended to better target vaccines toward people disproportionately impacted by Covid, OHA spokesman Rudy Owens said in an email. Clinics are still encouraged to prioritize according to the state’s schedule.

Vaccination priorities

The gaps are in part because of how Oregon has prioritized vaccinations to date.

Seniors make up a substantial portion of those now eligible for a shot, and account for the bulk of Covid deaths in Oregon. About 18% of Oregonians are 65 or older, versus just 5% of the state’s Latinos, according to 2019 Census data.

Statewide, agricultural and food processing workers become eligible for a shot March 29. Other groups of frontline workers, including grocery store employees, won’t be eligible until May 1 under Oregon’s current schedule.

But even once they’re eligible, community outreach and health workers say they face multiple challenges helping local Latinos get vaccinated.

Seniors across Oregon have seen long wait times and confusing online registration processes for shots, but those challenges are compounded for Latino seniors who may not speak or read English or have a computer in the home.

“Our elders are just not computer savvy at all,” said Reyna Lopez, executive director of Pineros y Campesionos Unidos del Noroeste, or PCUN, Oregon’s farmworker union.

Lopez said the group is working to expand outreach in the weeks before widespread farmworker eligibility. So far, she said the process has been too difficult to navigate.

“The systems aren’t accessible and we need to change that immediately or those same disparities that we’ve been seeing throughout the pandemic, they’re going to continue,” she said.

At the Lancaster clinic, Hill said employees knew scheduling appointments online would be a challenge for many of their patients, so clinic workers called all of their regular patients eligible to get a shot based on age and got them scheduled. They’ve also been able to vaccinate Marion County seniors who aren’t regular patients.

“That’s been pretty popular,” Hill said of the phone scheduling system. Clinic workers, most of whom are bilingual in English and Spanish, can also talk to patients who have concerns or questions about the shot’s side effects and whether it’s safe to receive.

Velasquez has been a patient at the Lancaster clinic for two years. She got her appointment scheduled with help from her daughter, who accompanied her to the clinic.

She was chipper as she waited for 15 minutes following the shot, saying she felt “more safe.”

“I was afraid to get other vaccines, but not this one,” she said. Why? She shrugged. “Maybe ignorance.”

Outreach in Marion County

Marion County’s health department is sharing information about the vaccine during a weekly segment on Spanish-language Radio Poder on Fridays, and started a Spanish-language vaccination campaign on Univision this week, health department spokeswoman Jenna Wyatt said. Those ads will run for at least eight weeks.

The health department is using 39% of its weekly vaccine allocation in the Woodburn area and north Marion County, Wyatt said, a higher share than either central Marion County or the Santiam Canyon.

That includes putting on weekly drive-through vaccine clinic with Woodburn Ambulance and the Interface Network, a Salem-based nonprofit organization focused on health care access. Wyatt said the county has also set up a vaccine planning committee with representatives from community groups including PCUN, Interface and local clinics and health providers to help guide local planning.

Marin Arreola, who coordinates Interface’s Covid response, said even with vaccines dedicated to Woodburn making sure they go to people who live in the area has been a challenge when supplies are so scarce across Oregon.

Interface has tried working with other community organizations to register people in advance before opening vaccine sign-ups to anyone eligible. But Arreola said the online link to register has been shared outside the groups they first send it to before they intended to make it public.

As a result, the clinics often have seniors driving down from the Portland area who have been unable to secure a vaccine appointment through the state’s more confusing system, he said.

OHA does not track vaccinations by ZIP code of residents, only by county, making it difficult to tell how widespread vaccine shopping is. The state encourages people to get vaccinated near where they live, but there’s no rule against traveling to get a shot, spokeswoman Delia Hernandez said.

“Right now, people are desperate so whatever doses that are out there, they go quickly and it’s basically survival of the fastest that can get to that,” Arreola said. “It’s going to take more work and more time to have Latinos get vaccinated.”

He said it took weeks of regular Covid testing events in Woodburn earlier in the year before those getting tested matched the demographics of the majority-Latino area.

Community organizers said they’re seeing hesitancy to get the vaccine among some local Latinos, which mirrors concerns they heard about Covid testing earlier in the pandemic.

“With the testing events we were running up against this idea people had with, ‘Well if I get tested, I’m gonna get the virus,’” said Levi Herrera-Lopez, executive director of Salem-based Mano a Mano. “Now with the vaccine it’s, ‘We know you’ve used us as guinea pigs in the past.’ It’s out there and we have to address it.”

Herrera-Lopez said those concerns can be addressed with good information, but that will take time and sustained outreach.

He recalled a Covid testing event geared toward Polk County farmworkers over the summer. Several residents of a nearby farmworker housing complex at first stood around, looking suspicious, he said.

“Little by little you could see them getting closer and closer and finally they went to one of the information tables,” he said. “Then they came back with like four other people wanting to get tested that night. That was exciting to me because little by little we were watching people get convinced and make the right decision.”

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Salem Reporter counts on community support to fund vital local journalism. You can help us do more.

SUBSCRIBE: A monthly digital subscription starts at $5 a month.

GIFT: Give someone you know a subscription.

ONE-TIME PAYMENT: Contribute, knowing your support goes towards more local journalism you can trust.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.