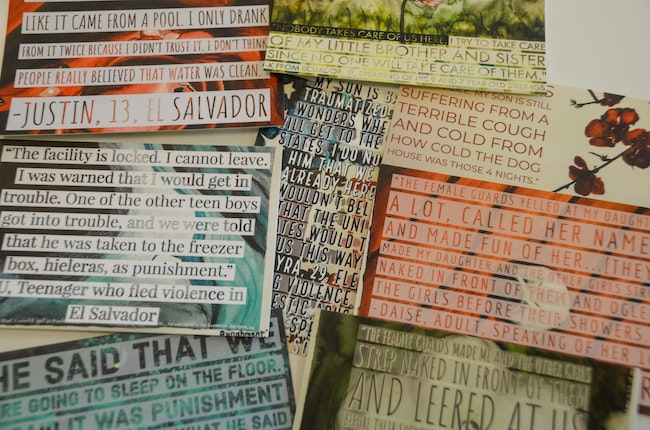

Postcards featuring the words of detained migrant children and their parents were featured at a Salem City Club presentation by Willamette University law professor Warren Binford (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Postcards featuring the words of detained migrant children and their parents were featured at a Salem City Club presentation by Willamette University law professor Warren Binford (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

“He said that we were going to sleep on the floor. He said it was punishment.”

That’s how a 7-year-old girl from El Salvador, detained with other children in a makeshift camp at a Texas Border Patrol station, described an agent’s reaction after her cell of children lost a lice comb they’d been given to share.

The girl’s words were on one of a handful of postcards passed out during a meeting Thursday of the Salem City Club.

Dozens in the audience fell silent as audience members took turns reading aloud the words of detained children, conveyed through a team of lawyers who visited the Texas detention center in June.

“My son is badly traumatized. He wonders when we will get to the United States. I do not tell him that we are already here. He wouldn’t believe that the United States would treat us this way,” a mother from Mexico said of her 9-year-old son.

Several of those listening shook their heads or simply stared down, as if ashamed.

[ Help build Salem Reporter and local news – SUBSCRIBE ]

“The facility is locked. I cannot leave. I was warned that I would get into trouble. One of the other teen boys got into trouble and we were told that he was taken to the freezer box, hieleras, as punishment,” said a teenager from El Salvador.

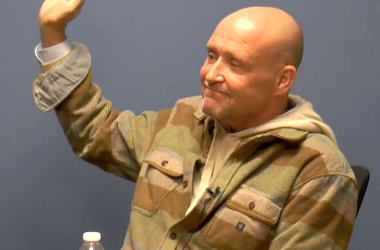

Warren Binford, a Willamette University law professor and specialist in child rights, was among the lawyers who visited the Clint, Texas, facility in June as part of a decades-old court settlement between the U.S. government and human rights groups. The agreement allows independent attorneys to monitor detention conditions.

Binford’s hour-long presentation mixed the history of federal law and policy toward migrant children with her own experience in Clint.

“Nothing prepared me for what happened when I walked into the Clint border facility,” Binford told the audience.

The lawyers’ observations received widespread national media attention with Binford and others describing extreme crowding, children forced to sleep on concrete floors, a lice outbreak, insufficient food and prepubescent children expected to care for infants and toddlers.

As she detailed what she saw in Clint with the clear but forceful speech of an experienced attorney, the Salem audience reacted emotionally. Some were moved to tears.

Following the talk, she received a standing ovation – the first that City Club member Jan Margosian said she’s seen since joining the group in 1969.

Binford’s central message was that the treatment of migrant children is far beyond what’s legally or morally acceptable – and honoring U.S. legal obligations to release children to relatives or foster parents in a timely fashion shouldn’t be a political issue.

“We as a nation are in danger of losing our humanity,” she said.

Willamette University law professor Warren Binford speaks about migrant child detention conditions to Salem City Club (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Willamette University law professor Warren Binford speaks about migrant child detention conditions to Salem City Club (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Binford told of of how the U.S. came to the current moment where children are routinely detained at the southern border without their parents or other relatives.

Lawsuits contesting the treatment of migrant children during the Reagan administration were eventually settled, establishing standards for the treatment of detained migrant children.

They require children to be released as soon as possible – and in no more than 20 days – to the care of a parent, adult relative or, in cases where they had no relative in the U.S., a licensed facility like a foster home.

And children in U.S. government custody were to be provided food, water and items for safety and hygiene.

That agreement was tested during the Obama administration with an escalation in Central American migrants coming to the U.S., in many cases to claim asylum. To file an asylum claim, a migrant must be physically in the U.S.

Binford attributed that increase to the erosion of local governance and the rise of gang violence, domestic violence and sexual assault which led many people to flee for their lives. She said an increasing number of indigenous people were leaving because of droughts brought on by climate change.

Many of those showing up at the border were “unaccompanied minors” – children and teenagers without parents or adult relatives. The Obama administration began locking them in detention centers, prompting lawsuits from human rights organizations.

“We were so mad,” Binford said of that era. At the time, children were being detained an average of 30 days, longer than child development experts said was appropriate.

Eventually, the Obama administration announced Central American minors with a parent in the U.S. could apply for refugee status from their home countries, meaning they wouldn’t have to make the dangerous overland journey to the U.S. and apply for asylum at the border.

The Trump administration ended that program in 2017.

Binford said that triggered a corresponding rise in minors and families traveling from Central America to the southern border. Now, she said, some children are detained for months and often without parents even after the Trump administration ended a policy requiring separation in most cases.

Border Patrol agents may still separate children from parents in specific circumstances, such as if the parent has a criminal record or appears abusive or neglectful.

But federal data obtained by advocacy groups shows hundreds of children have been separated since. Binford said the reasons can be flimsy – a parent with a traffic infraction or misdemeanor, for example.

She called that a narrow exception “the Border Patrol has driven a truck through.”

The June interviews Binford participated in came after several migrant children died in U.S. custody, prompting child welfare advocates to demand a closer look. The federal court settlement mandating the U.S. government to detain children in humane conditions also allows for inspections by advocates and attorneys.

She found the facility was caring for hundreds of infants and toddlers. Some children simply began sobbing when asked to describe the conditions. Most had the phone number of a parent or other relative in the U.S. memorized or folded into clothing but said they hadn’t been allowed to make contact.

“It was a Lord of the Flies scenario and it was created by our government,” she said.

Salem City Club members give a standing ovation to Willamette University law professor Warren Binford after a Sept. 26, 2019 speech about migrant child detention conditions. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Salem City Club members give a standing ovation to Willamette University law professor Warren Binford after a Sept. 26, 2019 speech about migrant child detention conditions. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Binford ended her talk by encouraging Salem residents to get involved, by reading and sharing testimony from children and signing up as short-term foster families for kids released from detention. She’s founded an advocacy group, Project Amplify, to collect and spread the children’s testimony and encouraged people to read those stories and donate to groups providing legal help to children, like the Texas-based RAICES.

That conclusion inspired some attendees who have followed the issue.

“I’m going to go home and do that stuff,” Margosian said.

Reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.