The industrial freezer in South Salem High School’s culinary classroom remains covered in handprints, left when students pushed the 600-pound appliance against a door to barricade themselves.

They were reacting, as trained, to a school lockdown initiated by a shooting involving students blocks from the school.

Teacher Laura Hofer hadn’t gotten around to wiping off the appliance five days after the incident.

There was never a shooter or other violence on campus. The March 7 shooting that led to a massive security response at South was in Bush’s Pasture Park, three blocks north of the school. In the park, one sophomore was dead, two other boys wounded.

The 2,200 students barricaded inside classrooms based on a report that the shooter from the park had returned to South. District officials and police later determined the report was inaccurate — only potential witnesses to the shooting had returned to school.

Students and staff said that last week’s violence and the resulting lockdown have caused lingering trauma, in some cases mixed with frustration that the larger south Salem community doesn’t understand what the school went through.

“The staff are not OK. The students are not OK,” Hofer said.

The knowledge that the shooting was in the park is little comfort to students, who consider Bush’s Pasture an extension of their campus – not a “nearby park,” as media reports and district statements described it.

The school track and tennis teams practice there, and the environmental club holds meetings among the oaks and picnic areas. Teachers take students to the park for hands-on lessons and students walk over to eat lunch or skip class.

“It very much is like this happened to us at our school,” said Noah Mayer, a junior.

“Bush is a part of South,” junior Sofia Castellanos said.

During the lockdown, a dozen students huddled in a pitch black orchestra closet, keeping phones in their pockets. They had no information beyond the lockdown level – three — which indicates an active threat inside the building. They worried the silence outside their door might mean classmates were being shot in another part of the school.

Some older students who focused on helping the freshmen in their class get to a safe place are only now finding time to feel their own emotions and cry.

“It’s been really hard for me to sit down and do my homework,” said Mayer. He didn’t know the sophomore killed but said he feels guilty now doing anything knowing that the boy’s family is grieving.

Classes at South have been emptier in the days since the shooting. Less than half of students attended class the day after the lockdown.

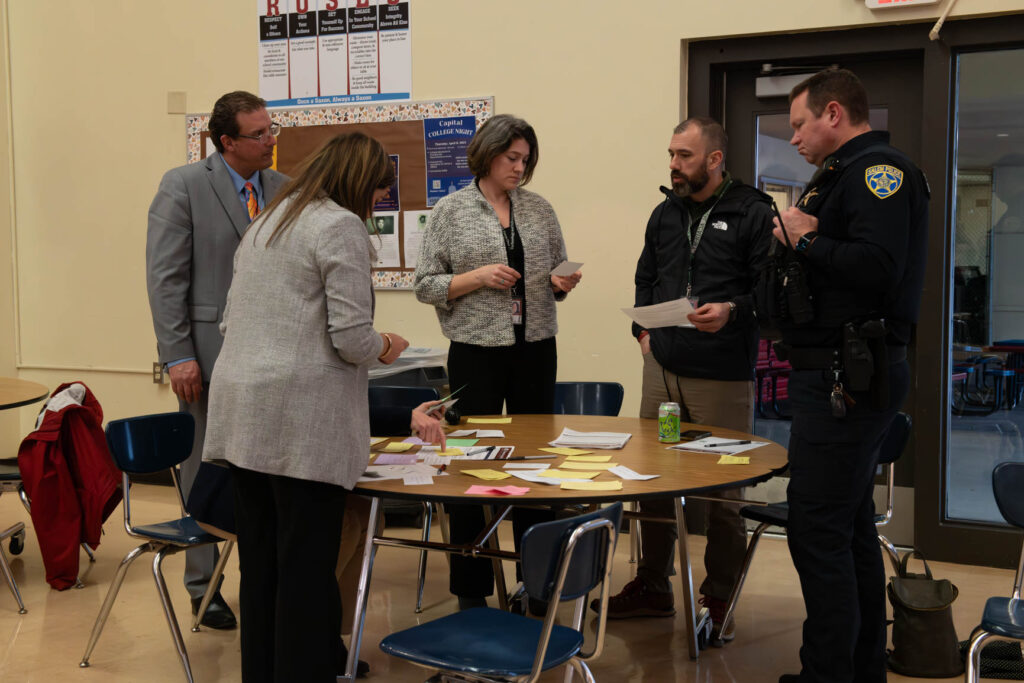

A Monday evening event in the school’s commons, billed as a “conversation about school safety,” was focused more on reassuring parents and imparting information about security procedures, several students who attended said. While the information shared was important, students and teachers who went through the lockdown need a place to get their questions about how the event was handled answered, said junior Brycen Martin.

Castellanos said it’s frustrating when they hear people outside the school ask, “But there wasn’t a shooting in South, right?” as if that should mean that South is OK.

“I don’t even feel like I get the privilege of being upset,” she said.

What happened at South

When shots were fired in the park on Thursday afternoon, half of South’s students were just returning from lunch.

Fourth period was starting in a few minutes, at 1:51 p.m. Some students were already inside their classrooms, talking to friends or getting ready. Some were coming back inside the building after leaving campus.

Police were called to the park at 1:45 p.m. A massive contingent of law enforcement descended on the 90-acre park within minutes, finding three teenagers shot and a small group of teens scattering.

In the school district’s security office, Chris Baldridge, director of safety and risk management, got word from police: lock down South and McKinley Elementary. He relayed the message to the schools.

Both schools went into a level one lockdown – the lowest of the district’s levels, generally used when police are pursuing a suspect or responding to a nearby incident unrelated to the school.

Baldridge and his staff began monitoring police radio traffic, staying in touch with law enforcement.

In the swirl of information circulating over the next two minutes, Baldridge heard someone say on school district radios that the shooter was inside South.

The school system’s response was immediate.

When the alarm rang inside her class indicating a lockdown, Hofer got up from her desk and walked to the main classroom door to lock it.

In the time it took her to reach the door, the alarm indicating a lockdown sounded again and an announcement flashed across the digital clock in her classroom: South was under a level three lockdown. “Barricade all doors and stay away from windows,” the scrolling red text read. A red light flashed.

Her fourth-period class is mostly underclassmen, with a few older students who serve as leaders.

Senior Miguel Orozco said he and his classmates reacted instinctively, barricading the four other classroom doors as they’d practiced during drills and telling students to go shelter in the back of the kitchen by the washer and dryer.

“There was no communication – we all kind of knew what to do,” he said.

Castellanos was in the hall heading to Spanish class when the alarm sounded. She ran into the nearest classroom and spent the lockdown with eight other students and a teacher she didn’t know well.

“The small numbers made you feel a lot more exposed,” she said.

Initially, students thought it was a drill, though Castellanos said the teacher’s face quickly made it clear staff hadn’t been expecting a lockdown.

“We were all quiet and the quiet made the anxiety rise,” she said.

While huddled in the classroom, Castellanos stayed in touch through a group text with about 25 classmates in the school’s International Baccalaureate program. They shared what they knew.

Mayer and Martin were in the school’s orchestra room waiting for class to start. They moved into the instrument storage room, joining about a dozen students and their teacher, huddled, trying not to move.

With no windows to the outside, the room was dark. Students kept phones away, so they had no way to monitor what was happening.

As the alarm sounded, Mayer said a part of him felt it was inevitable that he’d face an active shooting at some point before graduation.

“I was just waiting to hear footsteps and gunshots,” he said.

At 1:58 p.m., a message went out to South parents and families indicating the school was in a lockdown and providing few other details.

Police searched the school, ensuring there was no threat in the building.

Some secured in classrooms heard footsteps in the halls, leading to more panic that they were in immediate danger.

Silence provoked reassurance in some classes and anxiety in others.

Junior Yareli Caballero was in English class on the school’s second floor and said she and her classmates assumed they were safe because they didn’t hear anything outside the classroom door.

In some classes, students checked phones and communicated with parents for more information. Many learned about the shooting at Bush’s Pasture Park from media reports as they scrolled on their phones.

“I had no idea what was going on until my dad started texting me more information,” Caballero said.

Twenty minutes after families received word their students were barricading inside classrooms, the school downgraded the lockdown to level 2. “All students and staff are safe,” the message read.

In Hofer’s class, a team of SWAT officers unlocked her classroom door and told her and her students they were safe.

The minute before the door opened was tense, Hofer said. She had no idea who was outside her classroom. The sound of a key in a lock still causes her to freeze.

“Little things hit you,” she said.

The school lifted the lockdown just before school ended at 3:20 p.m. – nearly 90 minutes after it took hold. After school activities were canceled and students went home.

The aftermath

When Hofer’s class left Thursday afternoon, furniture was still stacked against most of her classroom doors.

On Friday morning, it was gone. She later learned that school administrators, including South’s former principal, Lara Tiffin, worked late Thursday to clear barricades from classrooms.

“They came and removed everything so the kids didn’t walk into that,” she said, tearing up.

Hofer said she makes a point of forging relationships with students who often act out in school. They’re kids who have walls up, generally, she said, and are more likely to talk back or swear.

On Friday, they came pouring into her classroom.

“They needed a hug. They needed to be with somebody they felt safe with,” she said.

Extra police patrolled the neighborhood, and more campus security officers were visible in hallways.

Mayer and Martin met outside South at 8:15 a.m. They were among a group of 36 students heading to George Fox University for an orchestra performance to qualify them for state.

“We’re all there in our concert clothes like nothing happened,” Mayer said.

They did a group hug and boarded the bus to the event, where they took the stage to face judges who had no idea what they’d gone through less than 24 hours before.

Classes Friday started off with normal attendance, said Caballero.

But anxiety again settled over the school as vague online threats made against South and other district schools circulated in groups texts and on social media. More and more people called in tips.

Police and the school district officials investigated and deemed threats not credible. At the Monday forum, Superintendent Andrea Castañeda said the district should have communicated more clearly to parents what steps they took to address the threats.

“We should have messaged you and said, ‘We know this is happening. We’re investigating everything we are handling safety,’” Castañeda said.

As anxiety mounted, students began leaving early. Parents texted their teens, telling them to come home. Castañeda said in their shoes, she likely would have made the same choice.

Castellanos left school after seventh period, skipping her last class of the day.

“I’ve never felt so scared of a non-tangible thing before,” she said.

Caballero said her last class of the day only had five students.

Attendance at school Monday was 69%, up from Friday but still lower than normal.

The school was again targeted on Monday evening by a bomb threat minutes before the school safety forum was to start. Police cleared the building and determined the threat wasn’t credible, but to many students and staff, it felt like a cruel joke.

At the forum, Castañeda said the district is considering installing weapons detection equipment at schools. South students said they supported the measure.

Nothing at school feels normal, students said. Added security in the halls has reassured some students, while serving as a reminder for others that school doesn’t feel safe.

The school’s counseling office has been overwhelmed. Counselor Ryan Marshall said Tuesday that none of his staff had the bandwidth to talk about their own experiences – they were still in the thick of meeting with students.

Castellanos and some friends are planning to make teacher appreciation cards, saying teachers need support and acknowledgement too.

“They’re trying to deal with it while being our support system,” Castellanos said.

Related coverage:

Salem schools may get weapons detectors following Bush’s Pasture Park shooting

UPDATED: 16-year-old boy turns himself in, charged with fatal shooting at Bush’s Pasture Park

Community prays, calls for action after Bush’s Pasture Park shooting

Police identify 16-year-old boy killed in Bush’s Pasture Park shooting

“The kid died in my lap”: witnesses describe tragedy, mayhem as 3 shot in Bush’s Pasture Park

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

SUPPORT OUR WORK – We depend on subscribers for resources to report on Salem with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.