For Portland artist Jeremy O. Davis, the Bush House Museum in Salem is a beautiful property despite its “tainted history.”

The grounds belonged to the late Asahel Bush, who acquired it in 1860. Bush was founding editor of the Oregon Statesman newspaper, which he often used to express his cultural views, and co-founder Salem’s Ladd and Bush Bank.

But now, the museum, with the help of the Salem Art Association, looks to reimagine itself with the help of Davis, who completed portraits of two Black pioneers who lived in Oregon.

“They’re trying to change the context of the house and invite … more dynamic stories to be told through the house that was once, without mincing words, the home of a racist,” Davis said of the museum efforts.

A reception is scheduled from 4-6 p.m., Saturday, Feb. 11, to unveil the portraits depicting Ben Johnson and Beatrice Morrow Cannady.

“Initially I want people to appreciate the art. I spend a lot of time trying to make good paintings,” Davis said. “In realizing these are really good paintings, they move closer and start to investigate. I want people’s curiosity to be sparked.”

Matthew Boulay, executive director of the Salem Art Association and Bush House Museum, noted Davis and the exhibit’s curator, Tammy Jo Wilson, will be on hand at the Saturday reception.

“Please come meet the artist, meet the curator and, most importantly, see the art,” Boulay said. “These are extraordinary portraits that tell really important stories of two Oregonians. But they’re just also visually stunning. They bring you in and you want to spend time with these two.”

In choosing Johnson and Cannady as his portrait subjects, Davis noted there are few Black pioneers in Oregon.

He had heard of the story of how Ben Johnson Mountain — near the Jackson County, Oregon town of Ruch — was renamed in 2020 to replace the racial epithet that was long associated with it.

“That story was really impactful to me,” Davis said.

But it was Johnson’s life that also appealed to the Portland artist.Johnson was born in the South in 1834 before settling in Southern Oregon where worked as a blacksmith. Ben Johnson Mountain near the Jackson County town of Ruch, was named after him.

The story of Johnson appealed to Davis when he considered portraits for the museum.

“The idea that this guy was a worker, a blacksmith; (he was) respected, had property — a house — (and) a wife,” Davis said. “His story sounded like the American dream.”

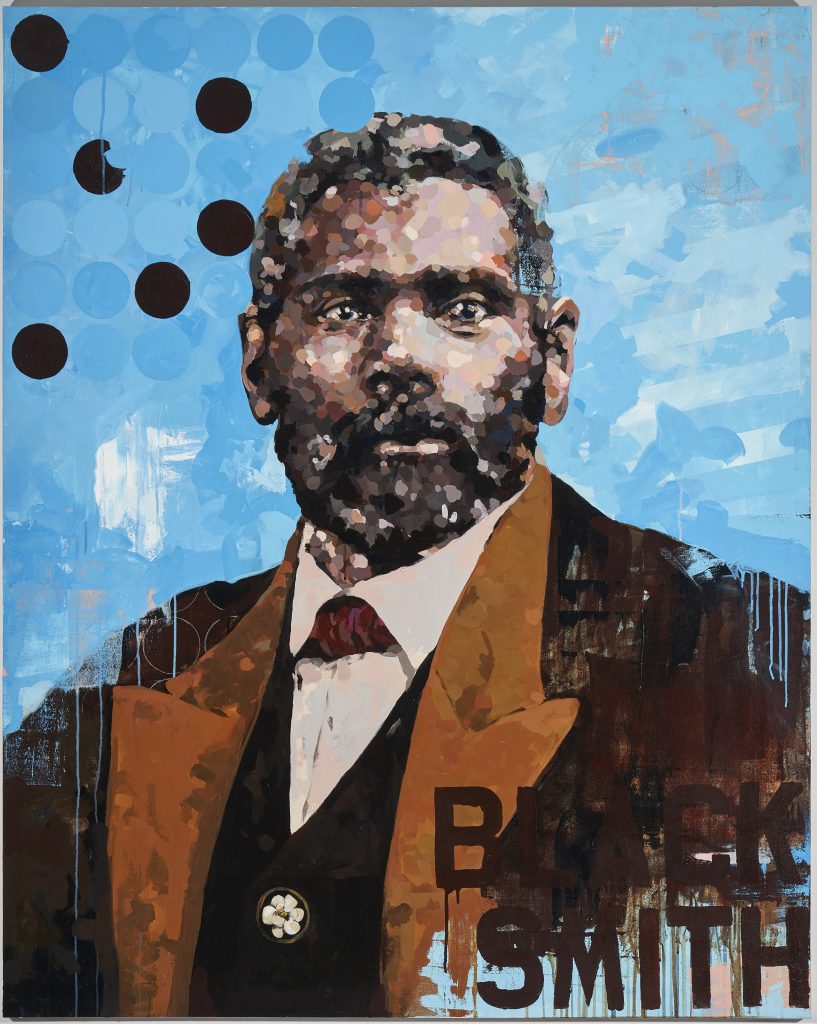

Davis’ portrait shows Johnson dressed in a nineteenth century suit. The word “Blacksmith” is painted in the lower right hand corner.

“He just looked so proper,” Davis said. “I loved his face. There was a sympathy, like vulnerability in his eyes. He had been through it, but he still was sitting up strong.”

In painting Johnson, Davis had envisioned a portrait of a woman as a sort of counterpoint to the blacksmith.

Cannady “was a nice balance,” Davis said. “In two pieces, it told a full story.”

Davis said part of his inspiration to paint Cannady came about when he heard news reports of a former Portland home of hers up for sale.

Davis’ portrait of Cannady is, like Johnson’s, framed shoulders and above, with the civil rights pioneer wearing a plain red shirt and necklace. Streaks of gray peak out through Cannady’s black hair — a detail Davis thought was key.

“In looking at her in that image, it felt like a life had been lived. Her eyes seemed really vulnerable and powerful at the same time,” Davis said. “The image spoke to me.”

Cannady, born in Texas in 1890, moved to Portland in 1910. It was then that she met her first husband, Edward Daniel Cannady, the editor and co-founder of the Advocate, Portland’s only African American newspaper at the time. The fact that Cannady’s life in newspapers shared a similarity with Bush was not lost on Davis when he selected her as his second portrait subject.

But he wanted to highlight Cannady’s ties to the civil rights movement involving her help to establish the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Cannady also became chief editor and owner of the Advocate, writing editorials criticizing how African Americans were routinely discriminated against in Portland. Cannady later graduated from Northwestern School of Law, using her education to help write Oregon’s first civil rights legislation.

Cannady died in 1974.Beatrice Morrow Cannady Elementary in Happy Valley was named after her.

The portraits of Johnson and Cannady tell a “full story,” Davis said, but he is also mindful of the fact that his 1901 death is not that far off from her 1890 birth.

“It’s almost like the passing of the torch in a way, without really knowing it,” Davis said.

Boulay applauded Davis’ work for the Salem Art Association and the museum, which has been trying to “reimagine” itself after being approached by a group called Oregon Black Pioneers.

“They said that in fact that Bush was a terribly flawed person, he was an advocate for the exclusionary laws, he was deeply racist — and we needed to tell that story more openly and fully,” said Boulay, who noted the group’s approach occurred before he started working for the museum. “The idea is to hold ourselves more accountable to the history and story of Bush … But really, more importantly, to be more open and inclusive to the community.”

To do that, the art association and museum have sponsored artwork and events around African Americans. Tammy Jo Wilson has since been hired as the museum’s director of programming and introduced officials to Davis.

“His artistic practice centers on creating portraits of historical Black figures and reinterpreting them in a contemporary style,” Boulay said. “The idea of creating a series of early Oregon Black pioneers seemed to be a perfect fit.”

Boulay believes Davis’ two portraits fall in line with the museum’s efforts to change.

“These are people who Bush probably would not have invited into his house, given what we know of his views on people of color,” Boulay said. “We’re inviting them into the house, so to speak, and telling their story through these portraits in a way that challenges the way the house might have been run 150 years ago.”

SUBSCRIBE TO GET SALEM NEWS – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe today to get our daily newsletters and more. Click I want to subscribe!

Kevin Opsahl is the education reporter for Salem Reporter. He was previously the education reporter for The Mail Tribune, based in Medford. He has reported for newspapers in Utah and Washington and freelanced. Kevin is a 2010 graduate of Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington, and is a native of Maryland.