(Tiffaney O’Dell and Molly Filler of Pamplin Media Group)

(Tiffaney O’Dell and Molly Filler of Pamplin Media Group)

SALEM — Lobbying is largely synonymous with interest groups, but every year, government agencies big and small spend money to amplify their interests at the Capitol.

Yet lobbyists for the city or county you live in or the public university your children attend are working at taxpayer expense in the Capitol with the hope of gaining influence.

“That’s our tax dollars lobbying for more tax dollars,” said Julie Parrish, a former state representative.

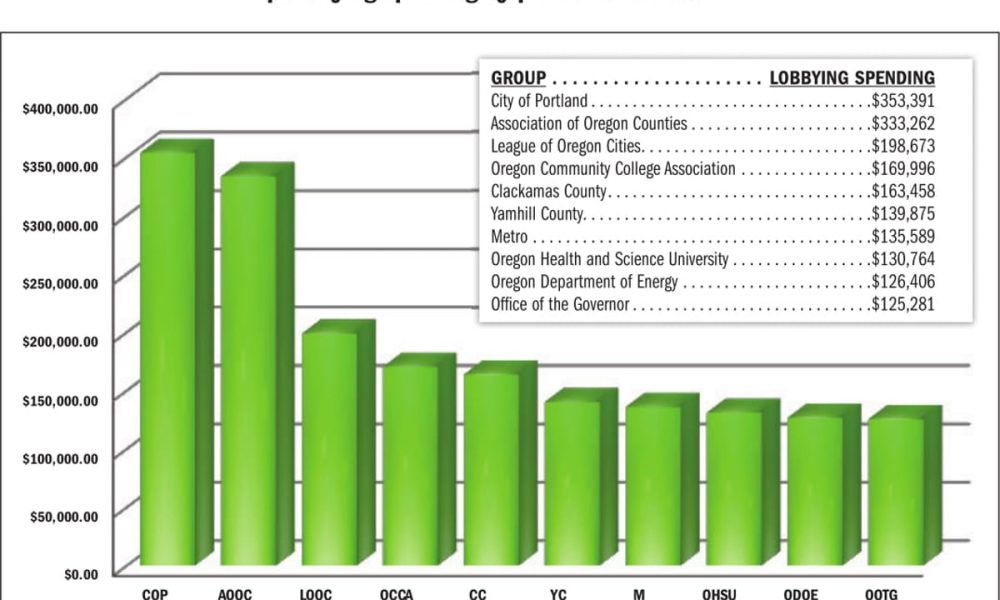

In 2017, the city of Portland spent more on lobbying than any other government body.

In fact, at $353,391, the city was the sixth biggest spender out of all organizations lobbying the Oregon Legislature.

City officials said they keep a close eye on the Legislature’s activities. In 2017, they tracked 2,091 bills out of the more than 2,800 introduced, and its lobbyists testified 70 times before legislative committees.

That year, many of the city’s interests advanced. Four of the five initiatives introduced at the city’s request became law.

Elizabeth Edwards, the city’s head of government relations, said the city lobbies on issues where it needs support from the state — or where it wants the state to allow local control.

The state’s most populous city, with than 640,000 residents, faces unique issues, Edwards said.

For example, the city wants to prevent fatal traffic accidents. City officials can’t on their own reduce speed limits on certain streets to cut the risk of pedestrians or bicyclists being killed in a collision with a vehicle.

So the city wants state legislators to pass a law this year to allow the city to reduce speed limits.

“I think people think of lobbyists as a really negative, nefarious figure, and really it’s about having better coordination between governments because we do all share constituents and are trying to find more efficient outcomes,” Edwards said.

Oregon’s cities and counties each band together to lobby for their interests.

The League of Oregon Cities was formed nearly a century ago, in 1925, through an intergovernmental agreement.

Each city pays dues to fund the league’s work.

Other organizations that represent public officials aren’t government agencies. One such example: the Confederation of Oregon School Administrators.

COSA, which counts public school administrators among its members, and whose board is made up largely of superintendents and administrators of public schools, spent $261,760 on lobbying the state in 2017.

COSA gets less than half of its funding from dues, which can be paid by school districts or individual members.

The Association of Oregon Counties spent about $333,000 on lobbying the state in 2017, making it the second-highest government spender on lobbying that year — just behind the City of Portland.

Oregonians rely on counties for more public services than in most other states, said McKenzie Farrell of the Association of Oregon Counties, a governmental entity representing the state’s 36 counties.

“This means that the majority of Oregon legislation has some potential impact on counties,” Farrell said. “Because of the depth and breadth of services that counties provide, we track more bills than any other organization in the state.”

State agencies also lobby the Legislature, as does the governor’s office.

Misha Isaak, general counsel to Gov. Kate Brown, said the office doesn’t hire private lobbyists to push Brown’s policy priorities.

But her policy advisors need to report how much time they spend explaining policy to lawmakers in an attempt to further her agenda.

Isaak said the governor campaigns on a policy platform. She’s expected to work to get that agenda passed by the Legislature. Having policy advisors work to that end is an “important and legitimate function of her staff,” he said.

Some of the governor’s desired policies are complex.

An example is the cap and trade program, which required a 98-page bill to frame.

But Kristen Sheeran, Brown’s carbon policy advisor, can break it down and explain it to committee members to inform them before they vote.

“She can go and meet with members of the Legislature and explain every part of that policy agenda from top to bottom,” Isaak said.

The Oregon Government Ethics Commission doesn’t track specifically how many lobbyists are registered with the public sector.

An Oregon Capital Bureau review of 2017 lobbying data found that at least 95 state agencies and local governments were registered as lobbying clients that year.

It’s not clear from the state ethics commission’s public database of lobbying expenditures what the money is actually spent on.

While one database tracks entities’ spending on lobbying, individual lobbyists also have to report the money they spend on food, drinks and entertainment for lobbying purposes every quarter.

That information is accessible on a public website.

But they don’t have to disclose what they are spending money on — for example, if they buy dinner or a round of beers — just the total dollar amount.

They do have to explain what they spent money on if they spent more than $50 on a single occasion on a legislative or executive branch official, though.

They also have to report any spending that their clients reimburse.

Public sector lobbying occurs in other states as well.

From 2014 to 2017, lobbyists for the public sector in the 20 states tracked by the National Institute on Money in Politics spent about $315 million on lobbying at state legislatures.

The National Conference of State Legislatures maintains a list of state regulations on lobbying by the public sector. Some states don’t allow government agencies to spend public money to retain a lobbyist.

“This could mean that agencies have no designated representative to communicate with the legislature, but often this means that an agency may only use full-time employees in dealing with the legislative branch,” NCSL states on a web page devoted to the topic. “Some states require agencies have a designated person to act as a liaison, while others provide for a special class of lobbyist. Other states’ laws are completely silent on the matter.”

Reporter Aubrey Wieber: [email protected] or 503-575-1251. Claire Withycombe: [email protected] or 971-304-4148. Aubrey and Claire work as part of the Oregon Capital Bureau, a collaboration of EO Media Group, Pamplin Media Group, and Salem Reporter.

TRY A FREE SAMPLE – You can see for yourself the kind of local news reporting brought to you by the team of professional reporters at Salem Reporter. You can read us for free for 30 days. Signing up is easy and gives you 24/7 access to our reports. Sign up HERE.