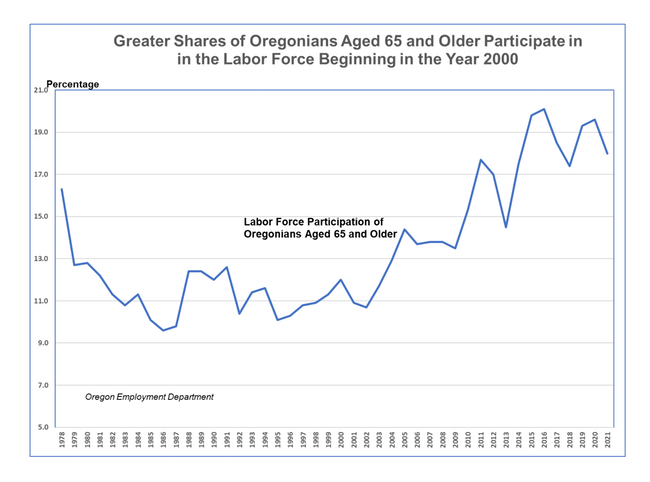

The share of older Oregonians working has increased over the past two decades. (Graph by Pamela Ferrara/Special to Salem Reporter)

The Oregon economy is currently experiencing the tightest labor market on record, with seven unemployed job seekers for every ten openings.

Employers looking to fill job vacancies should take note of the following: People aged 55 and older are the only age group whose labor force participation has been increasing over the last few decades.

What have been the trends in older people’s labor force participation, and what are predictions for the future? Why are more older adults working and looking for work? Is workforce policy taking account of this trend by providing specialized services to older job seekers? And are employers willing to hire older people who haven’t been employed in a while?

First let’s take a closer look at historical trends.

The share of Oregonians aged 65 and older working or looking for work has been increasing since about the year 2000 (see top graph).

This has been happening while participation rates for other age groups declined or were flat (see graph below).

Labor force participation among most age groups has declined in Oregon (Graph by Pamela Ferrara/Special to Salem Reporter)

Labor force participation among most age groups has declined in Oregon (Graph by Pamela Ferrara/Special to Salem Reporter)

In addition, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that, over the next decade, each age group of those over aged 55 will participate in the labor force in a greater share than they did in the year 2000 (see table below). Possibly the most startling of these projections is that the participation share of adults aged 75 and older will more than double by 2030, from 5.3 percent in 2000 to 11.7 percent in 2030.

Labor force participation among Oregonians 55 and older is increasing in every age group (Table by Pamela Ferrara/Special to Salem Reporter)

Labor force participation among Oregonians 55 and older is increasing in every age group (Table by Pamela Ferrara/Special to Salem Reporter)

Let’s look at both sides of labor force participation, working and looking for work. In the year 2000, 11.4% of Oregon workers were aged 65 and older. By 2019, that percentage had grown to 18.7%.

The unemployment rate for job seekers aged 65 and older (4.5%) wasn’t much different than the unemployment rate for those aged 25 and older (4.9%) in January of 2022.

What is different is that when older people look for work, it takes them longer to become employed, as much as 10 weeks longer than younger workers. Some reasons for this include: skills that are out-of-date and not a good fit for job openings; the need for more job search assistance than younger job seekers; health issues prohibiting some types of work; a belief that they can’t compete with younger workers; and age discrimination.

Why are older people coming back into the labor force in greater numbers? A Pew study sums up the answer in its title “For Passion or For Money, More Seniors Keep Working.” Passion is difficult to measure, but a need for money isn’t. Why might older people need a job?

Firstly, Social Security benefits, the linchpin of many older people’s income, have lost buying power over the years, even though they are adjusted annually for inflation.

In 2021, the Senior Citizen’s League estimated that the average Social Security check had lost 28% of its buying power since the year 2000. And Social Security checks account for 90% of monthly income for approximately 20 percent of the elderly population. In Marion County, that’s 11,000 older people living almost exclusively on Social Security retirement benefits.

Social Security recipients did receive a 5.9% cost of living raise in January 2022, the largest increase since 1982. But a good-sized chunk of that was erased by the largest Medicare Part B premium increase in Medicare’s history – this premium is deducted from benefit checks.

The reason that Social Security doesn’t go as far as it used to is that the Consumer Price Index used to adjust benefits is not reflective of older people’s spending. The Index is intended to reflect the spending of workers. Most Social Security beneficiaries are retired. In addition, the elderly spend two to three times as much on medical care as younger workers do. And, health care costs have risen much faster than other categories of spending.

In 1987 Congress directed the Bureau of Labor Statistics to construct a Consumer Price index focused on the elderly and their spending patterns, for possible use in calculating Social Security benefit increases. So far, it has remained on the drawing board.

Add to the declining buying power of Social Security dollars the fact that participation in pension plans in the U.S. fell from 38% in 1980 to 20% in 2008. This translates into fewer elderly having pension income.

Older women, especially those living alone, are especially at risk of having inadequate income. In 2019, the poverty rate for all individuals was 12%; for women aged 65 and older it was 16%. This means that approximately 5,000 women aged 65 and older in Marion County live in poverty.

The one federal Department of Labor program specifically providing assistance to older job seekers, the Senior Community Service Employment Program (SCSEP), provides job training to those at 125 percent of poverty or below. The program has been providing these services since 1965 as part of the Older Americans Act.

The program’s budget is small – approximately $400 million for all 50 states. EasterSeals Oregon is the program provider in the mid-Willamette Valley area, with the capacity to serve 87 low-income job-seekers annually from Marion, Linn, Benton, Polk and Yamhill counties.

Many program participants have multiple barriers to employment, such as disabilities, lack of updated skills, being homeless or at risk of homelessness, and especially in rural areas, isolation. So, the SCSEP program works in cooperation with the Willamette Workforce partnership (the area’s workforce board), and dozens of community partners and employers to enable participants to get the help they need. The goal for participants is, first, stabilization of their situation, then subsidized job-training, and lastly, a move into unsubsidized employment.

How did the pandemic affect the job-seekers in the SCSEP program? Deb Sanchez, the program’s state director, said it was challenging, but the program provided remote and virtual training activities for participants so that their training and subsidized stipends weren’t interrupted. Participants have been and still are enthusiastically job-hunting.

Whether for passion, or because they need a job, or both, older job-seekers will be applying for area openings in greater numbers over the next years. The benefits they bring to a job include maturity, a strong work ethic, and the ability to work flexible schedules. Employers should give this growing labor force a serious look.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected].

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!