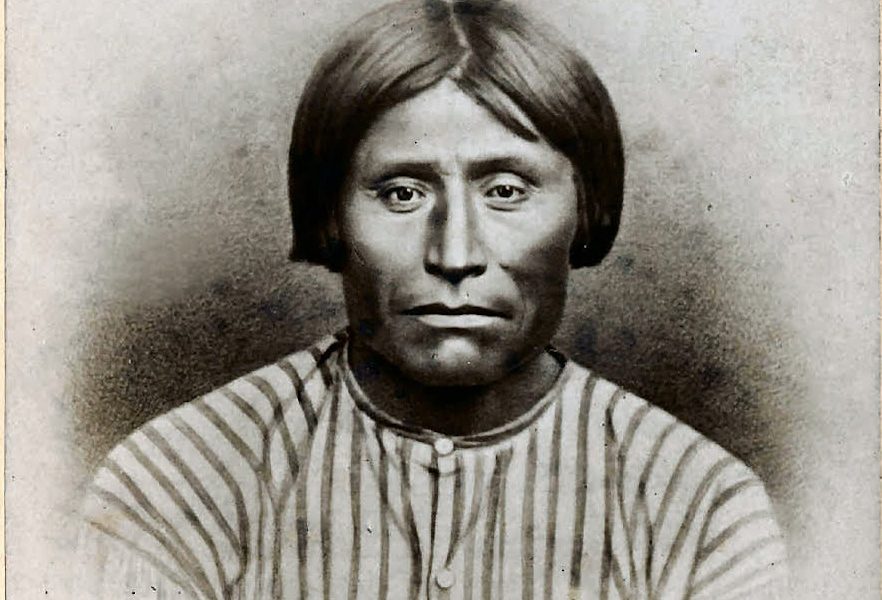

Kintpuash, known as Capt. Jack, once leader of the Modoc tribe. He was executed with three others after a standoff with the U.S. Army (Photo: Klamath County Museum)

SALEM — Nearly 150 years ago, the nation’s attention was fixed on a remote area near the Oregon-California border, where about 50 Modoc Indian soldiers were fending off a thousand U.S. Army soldiers from within a fortress of lava beds.

The Modoc War was a “David and Goliath war,” in the words of writer and historian Doug Foster. The six-month standoff that ended in 1873 was then the costliest American-Indian conflict in lives lost and money spent.

The war remains vivid in the collective memory of the Klamath Tribes, which include the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin Paiute Indians. Lava Beds National Monument has preserved battle sites from the war.

But state Sen. Fred Girod, R-Stayton, says broader awareness of the conflict — and subsequent execution of four Modoc Indians by the federal government — is needed.

Girod was so moved by a 2011 documentary by Oregon Public Broadcasting on the conflict and executions that he has proposed that Oregon express regret for the federal government’s execution of Modoc soldiers.

Senate Concurrent Resolution 12 originally stated “that we, the members of the Eightieth Legislative Assembly, commemorate the Modoc War of 1872-1873, and we recognize and honor all those who lost their lives in that costly conflict; and be it further resolved, that we express our regret over the execution of Kintpuash, Schonchin John, Black Jim and Boston Charley in October 1873 and for the expulsion of the Modoc tribe from their ancestral lands in Oregon.”

The legislation was subsequently amended to read that the state wants to “recognize and honor all those who lost their lives in that costly conflict,” and “express (the Legislature’s) regret for the expulsion of the Modoc tribe from their ancestral lands in Oregon.”

Girod’s proposal surprised the Klamath Tribes. Girod represents a Senate district east of Salem.

But they’re now strongly in favor of the commemoration and apology.

“Acknowledging the truth of wrongs done is a critical first step towards healing those affected,” wrote Donald C. Gentry, chairman of the Klamath Tribes, in a March 26 letter to the Senate Veterans and Emergency Preparedness Committee.

In 1873, a military commission that included officers who fought the Modocs tried six Modoc fighters.

They were sentenced to death after being found guilty of killing two peace commissioners, General Edward Richard Sprigg Canby and the Rev. Eleazar Thomas, “under a flag of truce.”

While two of the fighters’ sentences were commuted, Kintpuash — known also as Captain Jack — and three other Modoc men were hanged at Fort Klamath, according to a 2001 article about the trial by Foster, published in the magazine Southern Oregon Heritage Today.

The three other men were known as Schonchin John, Boston Charley and Black Jim.

According to Foster’s article, the trial received substantial media attention.

Taylor Tupper, a public information and news manager with the Klamath Tribes of Oregon, herself a direct descendant of Captain Jack and Schonchin John, said the resolution initially came as a “complete surprise.”

Tupper says the Modoc warriors weren’t given a fair trial. Among members of the Klamath Tribes, their deaths are viewed as murders.

“They were tried by the very same people that they fought in the war against,” Tupper said. “And so when you have Modoc people dying after a war and no officers in the Army dying for the same things and same transgressions against the Modoc people, then that’s blatantly unfair.”

After the war, Capt. Jack’s band was forced to what is now Oklahoma, then known as Indian Territory.

The federal government recognized the Modoc Indians as a separate tribe in 1978.

In his letter to the committee, Gentry said that the Klamath Tribes do not speak for the Modocs of Oklahoma.

“Though we may share many of the lasting traumatic and devastating effects of the Modoc War and the acts of genocide that occurred before and afterward, they have lived and survived through adversity that the Modoc people who were allowed to stay in Oregon on the Klamath Reservation never faced,” Gentry wrote.

The Klamath Tribes include the other bands of Modoc Indians who remained in the area.

During Wednesday’s hearing, where lawmakers took testimony from the public, members of the Klamath Tribes supported the proposal.

Cheewa James, who was born on the Klamath Reservation and wrote a book about the Modocs, told lawmakers that although the Modoc defendants were provided a translator, they were tried together without a lawyer.

And while they had broken a peace agreement and had weapons, James said, the peace commissioners brought weapons to the meeting as well, a fact not brought up at the trial.

“It was so wrong, what happened,” James said. “And, okay, it happened over 100 years ago. Things were different. But I think your efforts to rectify this kind of thing are very valuable.”

James’ grandfather and great-grandfather were sent to Oklahoma. Her father, who was born in 1900, was considered a prisoner of war until he was 9.

“I think it’s very healthy for the truth to be known about the war,” Gentry said in an interview. “We know that to the victor, they have the chance to write history. And the history that’s written for the most part, has been really from a real bias about what occurred and how it occurred and the motives behind it.”

The Modoc War didn’t involve just soldiers. Women and children from the tribe were fending off the Army’s advances as well, Gentry said.

Congress terminated federal recognition of the Klamath Tribes in 1954, and condemned 1.8 million acres of land that belonged to the tribes.

The Klamath Tribes regained federal recognition more than 30 years later, in 1986, but the tribes’ land rights were not restored.

There appears to be a growing recognition in Oregon — whose state anthem praises the land of “the empire builders” — that history has long been one-sided.

Two years ago, lawmakers passed a bill directing the state Education Department to develop a statewide curriculum “relating to the Native American experience in Oregon, including tribal history, tribal sovereignty, culture, treaty rights, government, socioeconomic experiences, and current events,” according the department’s web site.

The Modoc War will likely be included in that curriculum, Gentry said.

In testimony Wednesday, Girod compared the Modoc War to the 1836 Battle of the Alamo.

“That’s a story that’s ingrained in us since childhood,” Girod said. “I remember Davy Crockett, and John Wayne starring as Davy Crockett, and they were heroes, and they showed the valor that they possessed and they fought to the death.”

But while the standoff at the Alamo lasted 13 days, the outnumbered Modoc soldiers fended off the U.S. military for six months, Girod said.

Girod noted that the high school graduation rate among Native American students in Oregon is especially low.

Although the share of Native American high school students graduating on time has climbed by 10 points in the past five school years, it still lags behind the overall graduation rate, according to state government data.

In 2018, 79 percent of Oregon school students graduated on time, while 65 percent of Native American students did.

“I have maintained for a long time, some of that, is due to the way that we tell history,” Girod said.

After a unanimous vote Wednesday, the resolution now heads to the Senate.

CORRECTION: Legislation related to the Modoc War would “recognize and honor all those who lost their lives in that costly conflict,” and “express (the Legislature’s) regret for the expulsion of the Modoc tribe from their ancestral lands in Oregon.” An earlier story by the Oregon Capital Bureau incorrectly cited a previous legislative draft in reporting that the Legislature was moving to regret the execution of four Modoc Indians.

Reporter Claire Withycombe: [email protected] or 971-304-4148. Withycombe is a reporter for the EO Media Group working for the Oregon Capital Bureau, a collaboration of EO Media Group, Pamplin Media Group, and Salem Reporter.

Follow Salem Reporter on FACEBOOK and on TWITTER.

SUBSCRIBE TO SALEM REPORTER — For $10 a month, you hire our entire news team to work for you all month digging out the news of Salem and state government. You get breaking news alerts, emailed newsletters and around-the-clock access to our stories. We depend on subscribers to pay for in-depth, accurate news. Help us grow and get better with your subscription. Sign up HERE.