Anne Haskell knew she wanted to substitute teach after she retired in June 2021.

She’s been teaching in the Salem-Keizer School District since she graduated college in 1982, most recently spending a decade at Cummings Elementary in Keizer. Subbing would allow her to keep covering the cost of health insurance for her family.

Last August, Haskell attended a district Zoom meeting for newly retired educators hoping to substitute for the district. She filled out required paperwork near the end of the month and submitted it to the human resources department.

She has yet to set foot in a classroom.

As Salem-Keizer and other districts around Oregon have struggled with a staffing crisis this school year, some experienced educators are finding district or state bureaucracy is hindering their ability to help.

Haskell said the district told her and other newly retired educators in August that they didn’t need to reapply for a job at the district to be considered to sub. She had some hiccups – district workers originally sent forms to her school district email account, which she no longer had access to. But by October, more than a month after submitting paperwork, she still hadn’t heard back, even as former colleagues reached out to see if she could cover their classrooms.

Another friend who attended the August meeting was in the same boat, she said, and never got a response from human resources despite sending in paperwork to sub and following up.

Finally in December, Haskell said she heard from human resources after a school principal reached out on her behalf. Because months had passed since her retirement, Haskell was told she needed to apply as a new hire.

“It’s nine different forms I have to fill out … which they’ve had since I’ve been working there,” she said. “This has been the frustration – my other friend, he’s done with it. He’s not even going to bother with it anymore. So now you’re getting people who are willing to sub who are saying, ‘forget it.’”

Brian Turner, the district’s lead recruiter, said Haskell’s situation is not common, though he acknowledged a few substitute teachers got caught in back-and-forth limbo with the human resources department following the August meeting.

He said the district has hired more than 130 emergency substitute teachers and 50 restricted substitutes so far this year. Neither position requires prior teaching experience.

“Our numbers are pretty high for folks getting to work, and there are mistakes made occasionally,” he said.

Turner, who is himself a licensed teacher, took over the recruiter job in July and said he’s worked to improve district systems and create forms that better track retired teachers so they don’t slip through the cracks.

Of 14 retired teachers who attended the August meeting, he said seven are now working as subs and three dropped out of the hiring process, some because they didn’t want to get a Covid vaccine, which is a state requirement.

“Some people may not have been communicated with effectively, but we will rectify that if we haven’t already,” he said. (Haskell said Turner reached out to her and apologized profusely for the delays following his conversation with Salem Reporter.)

In Oregon, teachers and substitutes are licensed by the state Teacher Standards and Practices Commission. Prior to this school year, the commission had two pathways for substitute teachers: a regular substitute license, open to those with a teaching credential, and a restricted license, open to those with a four-year college degree who haven’t completed a teacher program.

In late September, the commission created a third option in response to staffing shortages around Oregon: an emergency substitute license for the 2021-22 school year.

Emergency substitutes don’t need a college degree and have to be sponsored by a school district, who must reimburse them for the $182 license fee and the cost of a background check. Licenses are only good through the end of June 2022, or for six months after applying, whichever is later.

For Angy Thomas, that sounded like a good deal.

She has a master’s degree in education and taught in the Salem-Keizer district for a decade, leaving in 2005 to become a children’s pastor. While between jobs, she substitute taught for a few years around 2015, but her teaching license expired in 2019.

Thomas went to a district training for prospective substitutes about a month ago and got a surprise: she couldn’t get an emergency license.

Because Thomas has a college degree and an expired teaching license, she’d have to apply for a regular substitute license with the state and pay late fees to reinstate her expired teaching certificate. The total cost, according to the commission’s fee schedule, would be close to $400.

“I am only considering stepping up in this season because there is a shortage, but this system seems punitive and that is disheartening,” she said in a text.

Anthony Rosilez, the commission’s executive director, said the emergency license was created to provide an option for people without a college degree to aid with the teacher shortage.

He said the district sponsorship requirement is in part because applicants without a college degree are likely less able to afford licensing costs.

“The emergency substitute license is only valid for the sponsoring district, so having the district pay for the license adds a degree of accountability to the school district to vet and provide support for those they wish to sponsor for the license,” Rosilez said in an email.

He said the commission has heard from several individuals and districts about licensing fees posing a challenge for prospective substitutes.

“The agency will continue to monitor feedback from districts and other individuals during the current staffing shortages and determine if further adjustments to the emergency or other substitute licenses are warranted,” Rosilez said.

A regular substitute license is good for three years and comes with other benefits not available under the emergency license, like the ability to be a long-term substitute.

Turner said he points those benefits out to prospective applicants, but he’s had several experienced teachers express interest in substituting only to be surprised to learn they have to pay out of pocket to get licensed.

“That has been really frustrating for folks that were expecting to get a reimbursement,” he said.

Turner said he doesn’t fault the commission for the guidelines and said except for the emergency license, there’s no precedent in Oregon for school districts reimbursing teacher licensing fees. Doing so only for substitutes, but not the roughly 2,000 other teachers the district employs, would create a pay equity issue, he said.

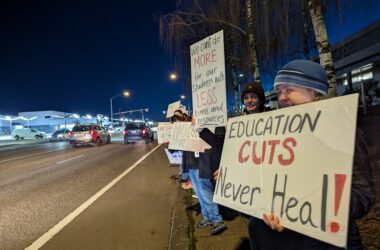

School board member Danielle Bethell raised the issue at a school board work session on staffing shortages Jan. 25. She told Salem Reporter she doesn’t understand why the commission is willing to waive licensing fees for those brand new to teaching but not experienced educators who want to help.

“They are who we want in classrooms! They have the experience we need to expedite them into classrooms and relieve some burden on the current system,” she said in a text.

Thomas said both the district and state commission offices have been helpful, but she’s still on the fence about whether she’s willing to pay the fees just to help out this school year. She said it would take about three days of work as a sub for her to break even.

“I only wanna sub during the subbing shortage … but it seems that isn’t an option for us with degrees,” she said in a text. “My degree and experience in education are my barriers.”

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.