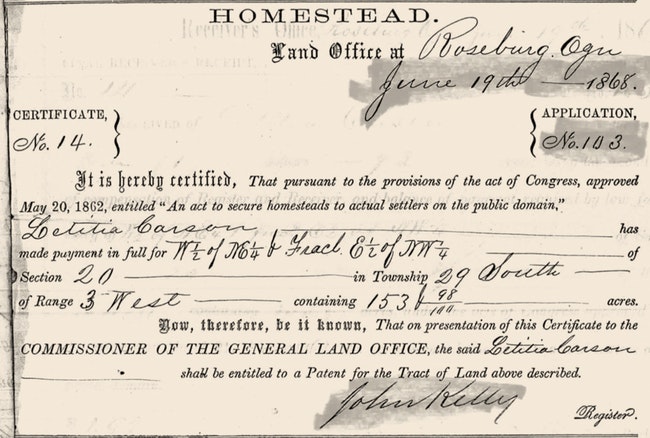

Letitia Carson’s Homestead certificate (Oregon Secretary of State)

A new grant awarded to a Salem-based historical society will help preserve the memory of one of the first Black pioneers to live in Oregon, a little-known figure in regional history who set a major legal precedent.

Oregon Black Pioneers is embarking on a project to recognize and publicize the legacy of Letitia Carson. Carson, a former slave who moved to the state in 1845, lost her husband and sued her neighbor over the rights to her own property – and won.

“She’s a really significant figure in Oregon’s history. This is the first time we have a Black person successfully suing a white defendant,” said Zachary Stocks, Oregon Black Pioneers’ executive director.

Last month, Oregon Black Pioneers received a $7,220 grant from Oregon Heritage to compile all the known information about Carson and her husband, David, and build a publicly accessible website. The organization will hire an intern from Oregon State University to develop the site’s back end.

The website is just the first step in a multi-phased plan. In 2022, the group is partnering with OSU, the Black Public Land Trust and the Corvallis chapter of the NAACP to continue a mission to preserve the Carsons’ historic homestead, located near what would later become Camp Adair just north of Corvallis.

Currently, OSU’s College of Agriculture owns the Carson property. It’s used as a working cattle ranch.

“Our project is going to try to take on the management of the historic portion of that ranch, where we can then begin the process of doing public education through onsite events,” Stocks said. “This grant we just received is for the first phase of the project, which is really to build out the digital components.”

According to Kuri Gill, grants and outreach coordinator at Oregon Heritage, the state’s historic preservation office awarded a grand total of $380,000 this year to 31 different organizations. The grant program, which operates biannually, prioritizes proposals that would elevate historically marginalized populations, Gill said. Projects with a time-sensitive preservation element are also given special consideration.

“We definitely got the highest number of applications we’ve ever had this year,” Gill said, adding that 76 organizations submitted requests this year. The previous record was 55. “Hopefully, we keep this trend up.”

Carson’s story

Because of Letitia Carson’s drawn-out legal battle, the details of Letitia and David Carsons’ life are exceptionally well documented for the time. Stocks credits two Oregon historians, Bob Zybach and Jan Meranda, with uncovering much of what’s currently known about the Carsons through their extensive research in the 1990s.

Based on the available primary documents, it’s known that the Carsons arrived in the state in 1845. Letitia, who had been born into slavery, was born in Kentucky and came to the northwest from Missouri. David was a white immigrant from Ireland.

“We don’t know if she came into Oregon as a freed person or an enslaved person,” Stocks said. “Sources point to the fact that they were a couple of choice, a consensual relationship between the two. That in itself is pretty unique in Oregon history at that time.”

The couple settled in Benton County, where they lived for seven years together and raised two children. In 1852, David died abruptly. The family’s neighbor, Greenberry Smith, was named executor of the state over Letitia.

It’s unclear why Smith, who was a white man, initially had the legal authority to claim the property. Smith began selling off the Carsons’ land, livestock and possessions.

“At the auction, Letitia had to use the money she had left to purchase back her own basic necessities,” Stock said. “All of the things she’d already owned.”

So she took Smith to court, filing two lawsuits against her former neighbor. Four years later she won both cases and was awarded $2,000 (worth about $65,000 today).

The crux of Carson’s argument, Stock said, was that Smith had illegally stolen her cattle and property under the assumption that she and her deceased husband hadn’t been truly married. “And if she were not legally David’s wife, she must have been his employee – and she never received any compensation.”

Until recently, Carson’s story was relatively unknown, and it still flies under the radar even among history buffs, Stocks said. But that’s already changing – in September, Corvallis School District renamed Wildcat Elementary School after Letitia Carson.

“Locally in Corvallis, her story is becoming more well known,” Stocks said. “She’s definitely becoming a figure known by name when they think about Oregon’s history, and especially Oregon’s Black history.”

Correction: This article originally misspelled Leticia Carson’s last name in some references. Salem Reporter apologizes for the error.

STORY TIP OR IDEA? Send an email to Salem Reporter’s news team: [email protected].

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!