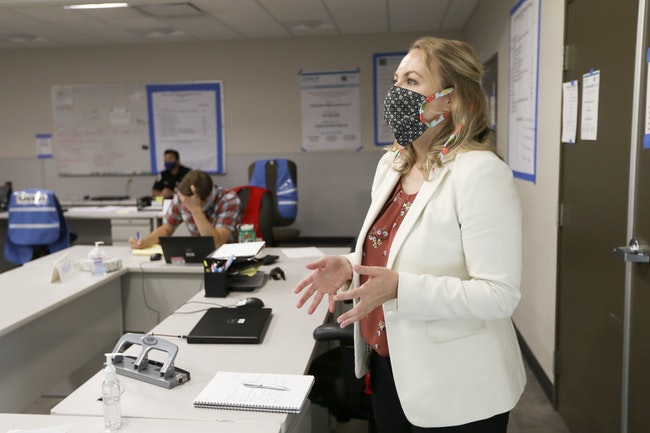

Katrina Rothenberger, incident commander, stands in the COVID-19 incident command at the Marion County Health and Human Services office on Monday, July 13, 2020. (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

Local public health officials say that a sluggish state system is impairing their ability to reach people testing positive for Covid, a key step in slowing the virus’ spread.

County health workers receive reports through a state data system called OPERA when a resident tests positive for Covid. They’re then supposed to call the person and question them about their symptoms, where they work or attend school, and other information that can help identify Covid outbreaks.

Health workers also give people information about the need to quarantine and where to get help with matters such as food when they need to stay home.

But in Marion County, those calls has slowed dramatically over the past month. The week of July 18, county health workers called 89% of people newly infected with Covid within 24 hours – just shy of a state target of 95%.

By Aug. 8, just 44% of people got that call within 24 hours, according to OHA data.

The delays are in part because lags in the state system now requires up to an hour of entry work for each new case, health department spokeswoman Jenna Wyatt said.

With Marion County now often recording more than 100 new infected people per day, there aren’t enough workers to make every call and enter the data.

“The lag time to enter data prevents our team from contacting each new case, meaning that some people continue to spread the virus unknowingly and are not connected with resources needed to quarantine safely. We have notified (the Oregon Health Authority) of the system’s slow speed on numerous occasions throughout the pandemic, but they have failed to prioritize finding a solution,” Wyatt said in an email.

A county epidemiologist compared the lags to “taking a car that only goes 10 MPH onto the freeway. You’ll get where you’re going eventually, but it will not be as quick as it could have been,” Wyatt said.

She said county officials asked OHA for more staff to help with case investigations and were told on Aug. 11 that none was available.

The state agency disputed that. Spokesman Timothy Heider said Marion County “has not reached out to OHA recently seeking support for case investigation” but didn’t offer further details.

“Many counties are currently in the same situation as Marion County and public health follow-up numbers are low across the state,” Heider said in an email. “During times of surge, we understand that (local public health authorities) will not be able to reach all cases in a timely manner. This surge is also causing performance issues with OPERA and we are working to identify solutions,”

Polk County has fared better with the surge, state data shows. The week of Aug. 8, health workers contacted 88% of people who tested positive or Covid within 24 hours, a drop from the 96% to 99% contact rate recorded in prior weeks. The county last week recorded 183 new cases.

Jacqui Umstead, Polk County’s public health administrator, said her staff can work around slowdowns in the state system, but have still seen some outages, like on Aug. 5, when the state system was unavailable for seven hours.

“We work around this by using an offline fillable form to interview the case and then we upload it to OPERA. This can help save time. However it is sometimes challenging to get even the phone number for the positive case from the database,” she said in an email.

Marion and Polk county public health administrators raised similar concerns with the state’s lags and outages last December, during another spike in Covid cases.

Commissioners in both counties brought up the database lags in interviews with Salem Reporter last week, saying they’re an example of how state agencies and Gov. Kate Brown could be doing more to help local governments combat rising Covid infections.

That issue has become a flashpoint following Brown’s decision to impose a statewide mask mandate, which took effect Friday, Aug. 13. The governor acted after saying that county leaders were unwilling to impose new restrictions and were putting Oregonians at risk as the more contagious Delta variant of the virus spread.

Marion and Polk county commissioners said they wouldn’t impose their own mask mandates.

Craig Pope, Polk County commissioner, said he raised the database lag issue in a call with Brown the week before she imposed the mask mandate.

“She was challenging us on what are we going to do about the pandemic and of course we all said we’re doing everything we can,” he said.

Asked what the governor did in response to county concerns about the ongoing database issues, Charles Boyle, a spokesman for the governor, said county leaders were “playing politics and trying to deflect blame, while the people they are supposed to represent are filling our hospital ICUs and overwhelming nurses and doctors.”

“By August 6 OHA was already addressing software reporting issues with local public health partners, and was standing ready to provide additional testing and contact tracing support to any county that needed help,” Boyle said in an email. “With test positivity rates high, though, it was also clear that the Delta variant was spreading rapidly and that community-wide measures like indoor mask requirements were needed to slow the spread.”

He added the state has requested federal help to provide additional health care workers and deployed members of the National Guard to hospitals.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

JUST THE FACTS, FOR SALEM – We report on your community with care and depth, fairness and accuracy. Get local news that matters to you. Subscribe to Salem Reporter starting at $5 a month. Click I want to subscribe!

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.