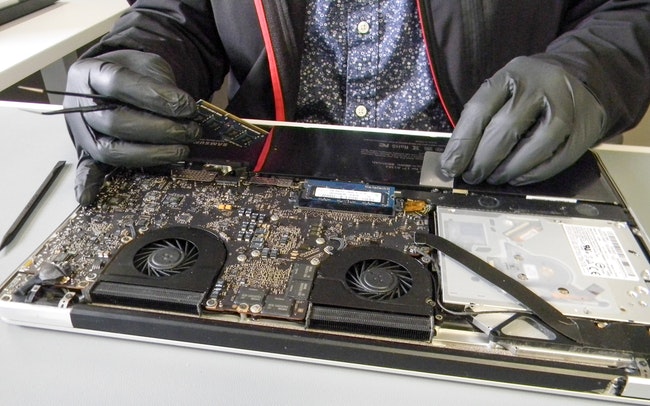

Brant Walsh, the owner of Salem-based repair shop The Mac Guy, opens up an older MacBook Pro to replace its battery. (Jake Thomas/Salem Reporter)

Brant Walsh’s business, The Mac Guy, was typically booked a week and a half out for appointments. But with Salem residents increasingly relying on the internet for school and work because of the pandemic, they dusted off aging PCs and MacBooks and brought them to Walsh in hopes he could get them working.

Now, he’s booked out a month in advance.

As in an independent shop, Walsh said he can get high-quality replacement batteries, hard disks and screens for Apple laptops and desktop computers. But he said Apple could start preventing third-party replacement parts from being installed on its products, which the company has already done with older iPhones.

“I might hook it all up, turn it on and it’ll say, ‘Your display is not officially supported, please return to Apple’ or something like that,” he said.

Someone with a broken Apple computer would then have no choice but to send it to the company for repair, which could take longer or be more expensive. Other manufacturers have long taken steps to prevent consumers from fixing their devices or taking them to independent repair shops.

But that all could change under a bill making its way through the Oregon Legislature.

Currently, many manufacturers of consumer electronics only allow authorized repair shops to access parts, tools, software or documents needed to repair their products. House Bill 2698 would establish a “right to repair,” requiring electronics manufacturers make them accessible to consumers and independent repair shops.

Proponents of the bill — which includes small repair shops, as well as environment and consumer advocates — say it would cut down on electronic waste while making computers and other devices more accessible. But industry groups say the bill could harm consumer privacy and there are already ways to get devices repaired.

State Rep. Janeen Sollman, a Hillsboro Democrat who sponsored the bill, told a legislative committee last month that the pandemic has highlighted the need for affordable technology with so many students and workers stuck at home.

“Access to the internet is essential to participate in our society,” she said. “Yet some low-income Oregonians do not have access to devices necessary to connect to the internet.”

She referenced an estimate that more than 75,000 computers were needed by students to support distance learning. Removing barriers to repairing computers would make them more accessible, she said.

Consumers who want to repair their laptops, cell phones or other devices, might have to travel miles to an authorized repair store or even have to mail it out of the state or country, she said.

Sollman said she’s narrowly tailored the bill to common consumer electronics, leaving out tractors, HVAC equipment, automobiles and medical devices. But the bill has still drawn opposition from industry groups.

The Consumer Technology Association, a national trade association that represents over 2,200 tech companies, said in a letter to legislators that the state’s electronics recycling is the most advanced in the country and there is an already thriving repair and reuse market.

Amanda Dalton, on lobbyist for industry group TechNet, told the committee that the bill would allow repair shops unauthorized by the manufacturer to access consumers’ sensitive data as well as proprietary information. She also said the bill’s definitions are too broad and there hasn’t been an effort to find middle ground.

“That’s because when it comes to the serious risks to the safety and security of electronic devices and consumer privacy concerns there really is simply no middle ground,” she said.

Sollman also pointed to a letter from the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality that said while the agency has no position on the bill, the legislation does align with the state’s policy of prioritizing the repair and reuse of products over recycling them.

Oregon has banned computers, printers, monitors and TVs from landfills since 2010, and over 11,000 tons of electronics were collected for recycling in 2019 alone, according to the letter. It further noted that these devices can be refurbished and provide an affordable option for consumers. Over 23,000 additional devices were reused in 2020, according to the letter.

According to a report from the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, Americans would save $40 billion ($330 per family) annually if they could repair electronic products. Fourteen states are considering similar legislation, according to the report.

Although Walsh, the owner of the local repair shop, signed on to a letter in support of the bill, he said he’s not “1,000%” on board with the right to repair. While he said it makes sense for independent shops to make repairs, he said some fixes should be left to the pros.

For instance, he said swapping out a broken battery can be dangerous if not done correctly. He said he puts on safety goggles and turns on a ventilator when he removes the strong adhesive keeping a computer’s battery in place. If the new battery isn’t put in correctly, it could malfunction and cause a fire.

“I don’t think you should just be doing that at home,” he said, adding that “lithium fires are not a good thing.”

Walsh said he could join Apple’s repair network. But he said it costs money to join. He’d also have to turn away 80% of his customers who have machines that are older than five years and considered “obsolete.”

He added that the fight over the right to repair itself might also become obsolete as electronic manufacturers increasingly make computers that have smaller and more integrated components that are more difficult to repair.

Jim Schroeder, the manager at Salem-based Norvac Electronic Parts, said that sometimes all it takes to keep a television or cell phone from being disposed of is a simple fix, said

Schroeder said that he’s had customers come in with broken electronics that just require replacing a transistor or diode, straight-forward and inexpensive repairs that can add years of use to the device.

But he said that sometimes customers bring in “mystery machines.” He said it’s uncertain what parts or tools are needed to fix these devices or even how to go about making the repair.

“Those mystery machines are hard to repair because you don’t know what’s wrong and how to diagnose it,” he said.

Contact reporter Jake Thomas at 503-575-1251 or [email protected] or @jakethomas2009.

Salem Reporter counts on community support to fund vital local journalism. You can help us do more.

SUBSCRIBE: A monthly digital subscription starts at $5 a month.

GIFT: Give someone you know a subscription.

ONE-TIME PAYMENT: Contribute, knowing your support goes towards more local journalism you can trust.