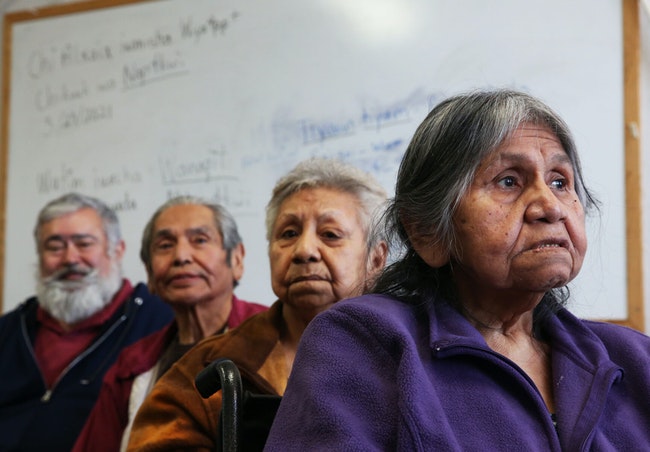

Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs elders from front to back, Viola Govenor, 82, Marcia Minthorn, 78, Willard Tewee, 72, and Lonnie James, 63, in a classroom where native language is taught on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. (Dean Guernsey/Bend Bulletin)

Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs elders from front to back, Viola Govenor, 82, Marcia Minthorn, 78, Willard Tewee, 72, and Lonnie James, 63, in a classroom where native language is taught on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. (Dean Guernsey/Bend Bulletin)

In a brightly lit classroom on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, sitting among other senior-aged language instructors, 84-year-old Viola Govenor closed her eyes and broke into song in Sahaptin, her native language. The melody rose and fell as the others listened intently to her impromptu song. There may not be many more times to hear it.

Govenor is one of the last speakers of her language, and there are fewer now in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which claimed the lives of more than 20 Warm Springs community members, some of them fluent speakers of their indigenous language.

The pandemic, which has cut short millions of lives, is now threatening the traditions and languages of indigenous people in Oregon. Those who know the traditions the best, the elder population, have seen their numbers dwindle to the point where the stream of knowledge is being undercut.

Govenor, who was hospitalized herself with COVID-19, lost friends to the disease and spent months in isolation. She missed the powwows and meetings. She missed out on funerals for loved ones. Mostly, she missed the opportunity to pass along knowledge of her fragile culture.

“We don’t get together too often anymore to share it with the younger generation,” said Govenor, wisps of gray and black hair framing a face burnished during a youth spent riding horses in the sunshine near her home on Mutton Mountain, close to the village of Simnasho.

“I thank the lord that I was able to leave the hospital and I am still here doing the work that I really enjoy. Our language has to go on,” she said.

Charles Tailfeathers, a Vietnam war veteran and vice president of the Warm Springs Veterans Memorial Park Committee, was one of the elders lost to COVID-19. He was a member of the Black Feet Reservation but spent much of his life at Warm Springs after marrying a Warm Springs tribal member. He worked for 20 years for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, where he assisted in creating a family wellness court system.

Shirley Stayhi Heath, the wife of Warm Springs Chief Delvis Heath, was another important member of the community taken by the virus. Heath was not only a leader for tribal affairs, she was also well-known on the reservation for her dedication to the Warm Springs elementary school, where she worked for nearly 20 years.

Arlita Rhoan also died from the virus. She was the lead language instructor at the Warm Springs Culture & Heritage Language Department. She is remembered fondly by Jermayne Tuckta, an archivist at the Museum at Warm Springs.

“She was fluent and she carried so much knowledge about spirituality, our ceremonies, our sacred foods, and everything,” said Tuckta. “She has taught many children, many teenagers, many students from our community, so when she passed that was a teacher who was taken away from us.”

Cultural knowledge

Elders carry with them knowledge of not only language but also songs, craft making, traditional foods, clothing, and other elements of this culture that stretches back to time immemorial but was severely damaged during the 19th and 20th century through forced assimilation by white settlers.

Much of the Warm Springs culture has been documented in books, videos, and audio files since the late 1990s, but there is little substitute for first-hand teaching. A program within the Warm Springs Education Department brings elders into schools to teach the culture to both students and educators.

“They are the pillars of our families so having them together like this is heartwarming,” said Valerie Switzler, general manager for the education administration. “It’s good for all of us.”

Switzler thinks it will be challenging to advance knowledge of the culture amid the losses but holds out hope it can be done. “I want to build a base of teachers who can teach children. We have promised those elders that we would never let the language die.”

A mile down the highway from the education building, at the museum, Tuckta, 32, is busy archiving photos and documents and gearing up for a project to have items digitized. He also spends much of his time teaching the Sahaptin language teachers. It’s something of a race against time as the number of speakers declines.

“All my mentors are going home,” said Tuckta, using a phrase to describe the passing of an individual. “We are definitely feeling the impact of their loss. One of the biggest things is the loss of fluent speakers.”

Tuckta says is working hard to teach the language to others.

“I don’t want to be the last speaker,” he said.

While different dialects of the language are spoken on several reservations in the Pacific Northwest, on the Warm Springs Reservation, there are just four fluent speakers left. Rhoan was one of those speakers.

In addition to language speakers, those who died from COVID-19 are also remembered for being an important bridge to earlier generations. According to tradition, only elders are permitted to correct others if they make a cultural error.

“Today because a lot of elders are returning home now, we don’t have those to correct us,” said Tuckta. “Even those who are left here today, because of the pandemic, they are not attending the ceremonies, they are not attending the funerals, so we are not getting that correction anymore.”

COVID-19 restrictions made customary funerals challenging. After a death, a person is typically mourned for several days with their body first in their home and then moved to the longhouse, a traditional gathering place at Warm Springs.

The body is dressed in traditional regalia and the family will eat three meals with the deceased individual. The home is cleansed and the person’s items are burned. Drumming, dancing, and singing are also performed. During the pandemic, the ceremonies and traditions have been condensed into just two or three hours.

“We have a certain way that we put our dead away; it used to be two to three days,” Marcia Minthorn, a 78-year-old community member, said on a visit to the education building.

“We haven’t been able to have our washat, our drumming, when we sing over the body,” said Minthorn. “We haven’t been able to dance around the deceased; it’s hurtful and very depressing.”

Lonnie James, 63, another community elder, said in several instances he only discovered the death of an old friend weeks or months after the friend passed away.

“When a person dies, it’s very important how we say goodbye. Now they are just sort of gone. We don’t have a way to mourn or grieve or acknowledge their passing,” said James.

Switzler from the education administration described the losses as “devastating.”

“Time does not respect anyone and we have lost many elders throughout these two decades of language work,” said Switzler. “However, nothing prepared us for COVID-19.”

Irreplaceable losses

Switzler spoke highly of Rhoan, who had been with the program since its inception in 1995 and served as an honorary professor at the University of Oregon.

Rhoan co-authored the Northwest Indian Language Institute’s language benchmarks, providing guidance and testimonies on senate bills including SB 690, which endorsed elders as teachers in the state of Oregon.

“Her loss was felt throughout the state and neighboring nations in Washington and Idaho,” said Switzler. “There is little we can do to replace her knowledge, experience, guidance, and background.”

Switzler said her administration is looking for new recruits that can become teachers and has connected with individuals who were enrolled in the language program in the 1990s.

She is also encouraging elders in the community to get vaccinated to prevent further loss of life.

“COVID-19 vaccinations will help protect our elders that protect our nation’s history, culture, traditions, and sovereignty,” she said.

While vaccinations will help to slow the spread of the virus, Tuckta still thinks resuming normal activities will take some time due to all that the community has been through over the past year.

“Even if everyone is vaccinated people are still going to be fearful for our elders because many of them have returned home due to COVID,” he said. “They are very precious to us and we don’t want to risk that chance.”

Back at the language center, 72-year-old Suaikt Willard Tewee, standing in front of a whiteboard covered with Sahaptin words and phrases, introduces himself in his native tongue.

“My name is There He Goes, the Wanderer, and I speak the language,” he states before reflecting on the pandemic year. “It has knocked us down, but we’ll dust ourselves off and get back up and go again.”

While the quarantines were a struggle, Tewee is grateful for the vaccinations. And even though is one of the last remaining speakers of his language on the reservation, he is confident it will continue after his death, with help from the education program.

“There will still be speakers after us. It’s not going to end with just us,” said Tewee. “There will still be people out there teaching the young ones. It will grow and grow and grow, we have a good archive here, so I believe it won’t be lost.”

This story published with permission as part of the AP Storyshare system. Salem Reporter is a contributor to this network of Oregon news outlets.