The employment picture in the Salem area during the pandemic has differed by sector. (Pam Ferrara)

The employment picture in the Salem area during the pandemic has differed by sector. (Pam Ferrara)

As the new year begins, let’s look back at the Salem economy since the pandemic began and then ahead to see how and when a return to normal might arrive.

Before March of 2020, the economy of the Salem area, like Oregon and the U.S., was in good shape with the lowest unemployment rate on record. Workers at all wage levels were beginning to see wage increases, which had stalled for many lower and middle-income workers for decades.

Then the pandemic hit. By May of 2020 the unemployment rate in the Salem area was 13.9%, its highest on record. The number of unemployed people in the area had increased from 7,000 to 26,000 in two months. During the 2008 recession, the number of unemployed in the Salem area took 17 months to increase from 10,000 to 22,000.

The April unemployment rate was unusual in other respects. In normal times, a person is unemployed because their skills aren’t what employers want, they’re employed in a seasonal job that’s ended, they’re between jobs or technology has put them out of work. The 13.9% unemployment rate was different. It was the result of government decisions to shut down parts of the economy for the purpose of slowing the spread of the virus.

Another unusual aspect of the high unemployment rate was its composition. Ninety percent of the unemployed had worked in the lowest paid service industries of the economy (mainly retail, as well as leisure and hospitality) and only 10% in goods-producing (construction and manufacturing). This is in contrast to the 2008 recession when half the unemployed had worked in service industries and half in goods-producing industries.

Usually in recessions, state tax collections take a hit and state workers are laid off due to budget cuts. This time most of the unemployed were low-paid workers who hadn’t paid much in the way of taxes. Higher income workers were still employed and paying taxes, so state government revenues stayed stable as did state employment. This is important to Salem because half of all state workers are located here and are a sizeable portion of the workforce.

After April and May, the worst months of the pandemic for unemployment, strict shutdowns were eased. The unemployment rate declined considerably over the summer as some people went back to work.

By November, the rate had dropped to just under 6%. But it wasn’t all good news, however, as some of the decline was due to shrinkage in the labor force. In the Salem area, there were nearly 4,000 fewer labor force participants in November 2020 than in November 2019.

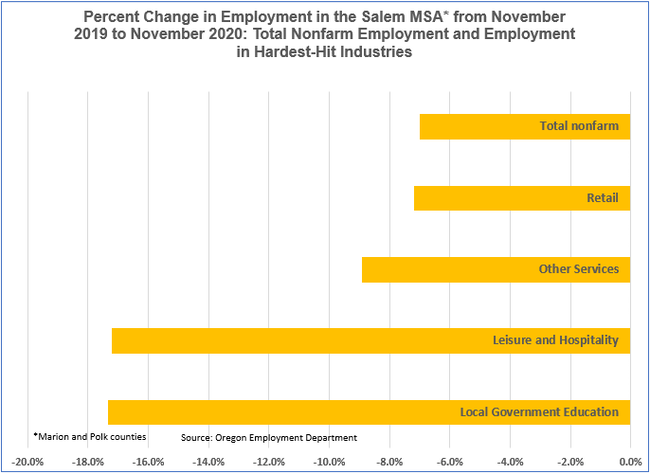

The lower unemployment rate in November (the latest information for the Salem area) meant that 10,000 people were still without jobs. These workers had been laid off from industries hardest hit by pandemic restrictions including retail, staffing agencies, health care and social assistance, leisure and hospitality, and local public education. Although total employment was down by 7% since the same time last year, these industries had double digit job losses and accounted for most of the loss.

The U.S. Census began a monthly survey last June to capture in real time the magnitude of economic problems being experienced by households in Oregon and across the country due to the pandemic.

In early December, according to the survey, 29% of all Oregon renters were not confident or only slightly confident about making their next month’s rent. Fourteen percent of homeowners weren’t confident about making their next mortgage payment. This translates into approximately 15,000 renter households and 11,000 homeowner households in Marion County worried about making housing payments.

Also in December, unemployment benefits began to run out for some 5,000 Salem area recipients, and federal programs from the stimulus package of early spring were winding down.

A one-day special session of the Oregon legislature in late December extended the eviction moratorium for renters for another six months and provided a fund to help reimburse landlords for delinquent rent. Recently the president signed a new stimulus bill passed by Congress that includes payments to individuals, as well as extensions of unemployment benefits and a program aimed at helping self-employed workers.

So how long will it take the economy to recover? It depends.

There could be a quick and complete recovery once the vaccine is in wide circulation. The recovery also depends on consumers spending money they’ve saved during the pandemic and a new federal stimulus relief bill staving off foreclosures and evictions while also helping unemployed and small business owners hang on a bit longer. The policies adopted by the incoming Biden administration could speed the recovery, such as aid to state and local governments.

Local governments provide vital services, such as education, police, fire, and sewer and water. But local governments are vulnerable. The city of Salem, for example, is projecting that revenues will not meet expenditures in the foreseeable future.

There could be a slower and more uneven recovery if the new federal stimulus doesn’t go far enough, labor force dropouts and unemployed workers don’t get the substantial help they will need to return to work, and if the lack of affordable day care and the high cost of housing aren’t addressed in some meaningful way.

These last two were problems for low and middle-income families before the pandemic. Housing and day care affordability have been made worse over the course of the downturn. But addressing them in a meaningful way will not be easy or cheap.

A big question mark, besides which of the two scenarios above is the most likely, is how our deeply divided politics will play out over the years to come and affect government’s ability to solve problems.

We’ll continue to track and analyze the consequences of the pandemic to the Salem area economy and public policy responses to it. Stay tuned!

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected]