After 9-year-old Briand Hermios finally got logged on to his virtual elementary school classes, his mother noticed he was missing needed supplies.

Hermios’ classmates at Scott Elementary School had whiteboards and pens to respond to the teacher’s questions live during class. He should have gotten the same items to take home, but there had been a mix up when the family moved over the summer, switching schools, and he had only the school-issued laptop.

Many parents facing such a situation might call the school.

But Hermios’ mother, Romanna Mike, understands little English. She came to Salem in 2015 from the Marshall Islands.

For help, she reached out to Kathleen Jonathan – the only Marshallese-speaking school outreach worker in the Salem-Keizer School District, the state’s second-largest.

Jonathan has been with the district since 2002 and serves as a bridge between Marshallese families and their local schools. She translates at parent-teacher conferences and checks in with students who are missing too much school to keep the students engaged. Many families can’t recall where they first met her.

“Word gets around,” Jonathan said, laughing.

Kathleen Jonathan, the Salem-Keizer School District’s only Marshallese-speaking school outreach worker, meets with a family at their home on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Kathleen Jonathan, the Salem-Keizer School District’s only Marshallese-speaking school outreach worker, meets with a family at their home on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

About 370 students across the district speak Marshallese as a first language, and with the entire district now attending school online, Jonathan has become essential to many Pacific Islander students and families who would otherwise struggle to communicate with their neighborhood schools.

Ken Ramirez, hired in 2018 to boost Pacific Islander graduation rates by serving as a mentor for struggling high school students, plays a similar role, making the rounds to students’ homes to check in and encourage them.

Jonathan and Ramirez report the students they work with regularly encounter language barriers and unfamiliar technology. They may live in large households where a half dozen students may be sharing one Internet connection.

The pair regularly drives to the east Salem apartment complex where Hermios and his family live. It’s a mix of one- and two-bedroom apartments set back a few blocks off Lancaster Drive and home to many Pacific Islander families, often with kids who attend Scott.

On an afternoon in October, Jonathan held a clipboard and worked with Mike filling out a form as Ramirez handed out pizza to kids in the courtyard, then played football with Hermios and other kids.

Mike, speaking in Marshallese through Jonathan, said in an interview that online school was going well for her son, though he’d only recently gotten connected to classes. Someone had to come over and show him how to log on, she explained – she hadn’t been able to.

Ramirez and Jonathan said it had taken several visits and some troubleshooting to get there, including bribing the boy with a soccer ball to attend regularly.

Once her son started attending, Mike noticed the missing supplies. Ramirez said she tried to visit the school to get the whiteboard herself before reaching out to Jonathan.

“She tried and they couldn’t figure it out. Language was a huge barrier,” Ramirez said.

Hermios said he missed attending school in person. His favorite part of school is science, he said, especially “making something cool” like a baking soda and vinegar volcano. Now, at home, he doesn’t get to do such projects.

For him, Jonathan is a familiar face.

“If I forgot the password, she helps me,” he explained.

Building personal connections

Personal connections and home visits are vital tools for getting many Salem students engaged in online classes, but Jonathan and Ramirez said they’re stretched thin and worry about their students.

On Oct. 29, the day of the visit to Hermios’ home, Jonathan said she was about a month behind responding to emails because of the volume of requests from families and local schools seeking help.

With so many requests pending, she has no time for proactive outreach.

“There are so many I’m probably missing,” she said.

There’s still little data on the impacts of online schooling locally or whether achievement gaps along racial and income lines are worsening.

State changes to attendance reporting require teachers to mark students present for online classes if they interact with a teacher at some point during the day, even if it’s sending an email, so they don’t give an accurate picture of which students are showing up to most classes. Still, district data shows Pacific Islander students so far have the lowest average daily attendance of any racial or ethnic group in the district, 91%.

Pacific Islander students come from a diverse range of cultural backgrounds including Filipinos, native Hawaiians, Marshallese students and those from the Chuuk Islands, part of the Federated States of Micronesia. Some grew up speaking English, while others are learning in school.

They make up about 2% of the district population, about 800 students. That share has grown in recent years, as has the number of Marshallese and Chuukese-speaking families.

While the district’s translation office employs speakers of both languages to translate forms and letters home, few schools have anyone on staff who can communicate directly with Islander families in their native languages.

School outreach worker Ken Ramirez, right, fist bumps Scott Elementary student Briand Hermios during a home visit on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

School outreach worker Ken Ramirez, right, fist bumps Scott Elementary student Briand Hermios during a home visit on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

It’s a gap the district is trying to fix with some new hires, said Sandie Price, Salem-Keizer’s director for strategic planning. Those include another outreach worker like Jonathan who speaks Chuukese, and a second like Ramirez who works one-on-one with middle and high school students.

School workers get creative to navigate language barriers and Scott Elementary has made a point of conducting home visits when students aren’t showing up online, principal Tracy Moisan said.

Counselor Lisa Rhoades often makes those trips, and said she and other school workers have worked over the past year or two to meet with families at home so they’re familiar faces.

Rhoades said technology issues which parents struggle to resolve because of language barriers remain a challenge, and some students don’t have a good space in the home to attend class.

“Right now we’re just going out to individual homes and basically troubleshooting,” Rhoades said.

They’ve developed schedules for the online school day that use visuals, rather than English text, to make it easier for parents to understand, and are working to find recent graduates and older family members who can help translate when needed.

Parents have been eager to help their kids online, both women said, often showing up at the school asking for help when technology hasn’t worked well.

But Moisan acknowledged language remains a challenge in reaching some families.

“Oftentimes leaving messages on the phone or sending stuff home, it’s not information that’s accessible to them right away,” Moisan said.

Teachers sometimes do their own visits, teaming up with Jonathan.

Doug Williams, a Scott teacher in his seventh year, coordinated with her for a parent-teacher conference with Mauto Joel and her son Henikam Lang, 9.

The family recently moved from Hawaii, and Williams said because the family spoke Marshallese at home, he wanted to visit with Jonathan and make sure they were settling in well instead of doing a virtual conference. They spoke on the steps outside the family’s apartment.

Joel reported she was confused by the school’s online class system. “I don’t know how to log in,” she explained. Despite that, Lang was a star in Williams’ class, always attending on time and dazzling his teacher and classmates with stories.

“He’s told me good stories of going fishing,” Williams said. Joel beamed.

Scott Elementary teacher Doug Williams, right, and Marshallese school outreach worker Kathleen Jonathan, meet with a family on a home visit on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Scott Elementary teacher Doug Williams, right, and Marshallese school outreach worker Kathleen Jonathan, meet with a family on a home visit on Oct. 29 (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

High schoolers thrive in-person

Older students are less likely to struggle with language, but family obligations and cultural differences can compound the challenge of being a teenager suddenly tasked with managing a school schedule from home.

Ramirez reported about half his students are regularly attending class on a typical day, and many were just getting online for the first time a month into the school year, often because they were confused about how to log on to classes.

He tries to visit students in person as much as he can, stopping by their homes to talk outside with masks on and let them know there’s an adult at school who cares how they’re doing.

In October, Ramirez stopped by McKay High School to grab some colored pencils, paper and other art supplies for a student, then loaded up his motorcycle and set off.

He dropped the supplies on a student’s porch, then knocked on the door of a ground-floor apartment in northeast Salem and tried to coax Dunly Juda, a McKay junior, out.

“Tell them your teacher Ken’s outside…No, you’re not in trouble! Why does it have to be bad? I can’t just miss you?” Ramirez said to the cracked open door.

Ken Ramirez, community outreach specialist, checks in with Dunly Juda, a junior at McKay High School on Thursday, October 8 (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

Ken Ramirez, community outreach specialist, checks in with Dunly Juda, a junior at McKay High School on Thursday, October 8 (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

Juda lives with his grandparents and had been doing relatively well with online school, though Ramirez teased him about sleeping in. They talked about his math class, with Ramirez making plans to bring a desk over so they could sit outside and work on assignments.

Mostly, Juda said he missed going out to see people and had trouble staying focused on school with everything online. His grandparents are high-risk for Covid and don’t want him going out much.

“I get distracted easily,” he said.

That’s not unusual for teenagers, but Ramirez said living arrangements and culture common to many local Islander families compounds the distractions.

Time is typically more fluid at home, he said, in contrast to Western cultures where daily life is regimented with appointments. Students who are used to sticking to a bell schedule at school have difficulty translating that into family life.

“You’re trying to merge those two and culturally that doesn’t work all the time with our students,” he said.

His next stop was a home in Keizer, where McNary junior Bryan Masasi lives with his parents and younger siblings.

Masasi said the pandemic has been hard. He misses seeing his friends and his younger siblings need help with school.

“What’s up with the classes?” Ramirez asked as they stood on the front lawn.

“I’m kind of failing,” the junior responded sheepishly.

“You can’t fail at something you don’t know how to do,” Ramirez said. “I know it’s hard – it’s hard for me with my kid. But you gotta reach out.”

They made a plan to meet at McNary later that week to work on assignments. Ramirez urged him to bring his siblings too.

“I’ll buy you lunch,” Ramirez said. “It’s that important to me – I’ll feed you guys.”

He said students struggling to do work at home often respond well when he makes an appointment with them inside a school for one-on-one help, but Ramirez can only meet with so many students in a week.

“It’s having that structure. Now all of a sudden they’re in a building, you see the wheels start to re-click again,” he said.

Correction: This article originally misspelled Mauto Joel and Henikam Lang’s first names.

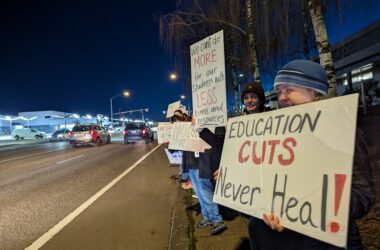

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

SUPPORT ESSENTIAL REPORTING FOR SALEM – A subscription starts at $5 a month for around-the-clock access to stories and email alerts sent directly to you. Your support matters. Go HERE.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.