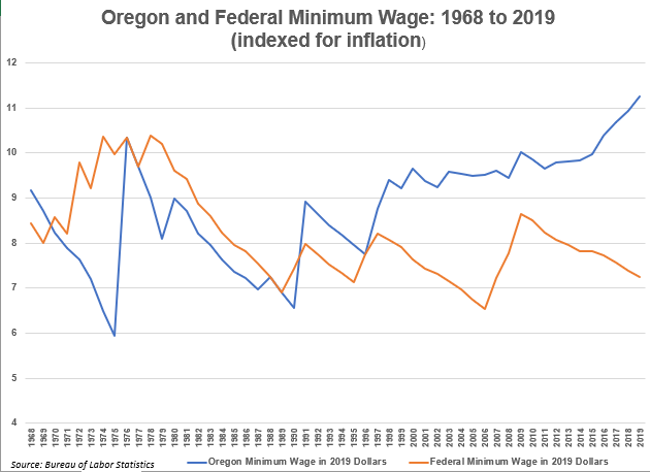

The federal government has taken a different approach to minimum wage than the state of Oregon. (Graph courtesy of Pamela Ferrara)

The Salem economy is improving. The unemployment rate has come down from nearly 14% in April to 7.3% in August. However, 14,000 people in the Salem area are still unemployed. Most of those people are included in the lowest-paying industries, a unique aspect of this economic downturn.

In addition, wildfires in the Santiam Canyon and days of dangerous-to-breath air have added to the economic misery of many area residents, workers and business owners. For an initial analysis of the impact of the wildfires on the area economy, see a report last month from the Oregon Employment Department.

The pandemic and the related economic shutdown have highlighted the importance of those workers who work at the lowest end of the pay scale. They perform work essential to keeping us going and allow many to work remotely in the safety of their own homes. Why do they make so little in the way of a paycheck?

A simple explanation for the gap in pay between highly skilled and lower-skilled workers is the law of supply and demand for labor. Skilled workers are in high demand and short supply; thus, they earn more. Lesser skilled workers are in greater supply and earn less.

However, the pay gap is also in part due to many complex and inter-related public policy decisions made by government over decades. These include making it more difficult to form unions, de-regulation, off-shoring of jobs, uneven application of anti-trust legislation and the deliberate structure of global trade. The minimum wage is a public policy solution to the pay gap that’s been legislated by federal, state, and in recent years, some local governments. Let’s take a brief look at its history, and some of the discussion around the economic effects of a minimum wage.

The idea of a minimum wage, that workers are entitled to a certain amount of pay for their work, is at least two centuries old. Silk workers in France went on strike in 1831 demanding a minimum wage (they didn’t get one) and New Zealand was the first country to legislate a minimum wage in 1898.

Massachusetts enacted the first minimum wage law in the U.S. in 1912, and the first federal minimum wage was part of the Fair Labor Standards act of 1938. Oregon enacted its first minimum wage in 1968 of $1.25 an hour, and it included a $1.00 an hour wage for minors.

Oregonians voted to index the minimum wage to inflation with the passage of a ballot measure in 2002, ensuring that the purchasing power of the minimum wage would keep up with inflation, and it has since then (see graph). The federal minimum wage is not indexed to inflation – it has been $7.25 since 2009 and has lost substantial purchasing power.

The Oregon legislature enacted a tiered minimum wage in 2016, recognizing that urban areas generally have higher wages than rural areas. The Portland area has a higher minimum wage, and most of eastern Oregon and the southern coast have a lower one. Salem’s is between the two at $12 an hour. All three tiers will increase yearly until 2022 and then again be indexed to inflation.

How many Marion County workers earn minimum wage, and what are their characteristics?

When the Oregon minimum wage increased on July 1 of this year, some 11,000 Salem area workers saw a larger paycheck (6% of the workforce). If the minimum wage had increased to $15 an hour, an idea much discussed over the last few years, another 55,000 Salem workers (those earning between $12.01 and $14.99 an hour) would have seen a bigger paycheck.

Slightly more than half of Marion County’s minimum wage earners work in just two industries, retail sales, and leisure and hospitality. These two industries that have borne the brunt of the pandemic-related shutdown.

Minimum wage earners are (according to the federal labor statistics agency):

· More likely to be women (63%).

· More likely to be young. The median age of minimum wage workers is 25. It’s 42 for all workers.

· Not likely to have a college degree, or any college.

· More likely to work part-time (65%).

· More likely to work for a small employer – large employers have a very small share of minimum wage workers.

What about effects on the economy? Economic theory says that having a minimum wage causes job loss. When the price of an hour of labor goes up, it is predicted that less of it will be used, all other things staying constant. We don’t live in the world of economic theory, however, and other things don’t stay constant. So, economists debate about the actual size of the job loss. Most research concludes that losses are in the 1 to 3% range.

Does the minimum wage keep wage-earners out of poverty? If a couple in Salem both earn minimum wage and work full time (2,080 hours in a year), they would earn nearly $50,000. The established poverty level for two people is $17,240. So technically the minimum wage keeps earners out of poverty.

The effects of a minimum wage no doubt will continue to be debated. What we can say for sure is that having one has been consistent public policy in Oregon and the U.S. for many years.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected]