A graph showing the percentage of total U.S. employment in goods producing and service producing industries from 1950 to 2018. (Courtesy/ Oregon Employment Department)

A graph showing the percentage of total U.S. employment in goods producing and service producing industries from 1950 to 2018. (Courtesy/ Oregon Employment Department)

The good news for Salem’s economy is that the unemployment rate has come down from 13.2 percent in April to 12.7 percent in May. The not-so-good news is that those still unemployed due to the pandemic shut-down were mostly low wage workers in service industries. This aspect of the current recession is unique, and will present challenges to an economic recovery.

To see why, it is helpful to understand some economic history.

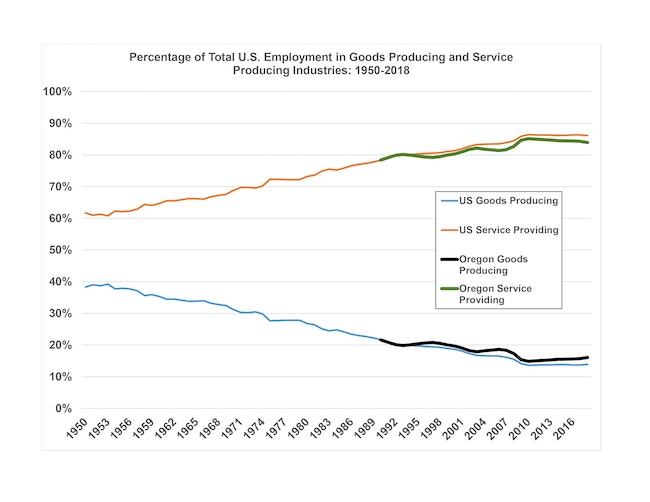

Our economy is now predominantly a service-industry economy. Since at least 1950, the mix of goods-producing jobs (agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, construction and manufacturing) and service-industry jobs (just about everything else) has been changing (see graph).

In 1950, 40 percent of U.S. jobs were in goods-producing industries, and 60 percent in service industries. Over the last 70 years, goods-producing employment in the U.S. has shrunk substantially as a share of total employment, and service employment has grown. Oregon and Salem’s economy have undergone this shift as well.

Why does this matter? For at least two reasons. This change in the industry composition of the economy has consequences in terms of workers earning good wages. Education beyond high school, licensure, and/or extensive job training are more important now to being employed at a good wage than in the past. This has produced a large divide between good-paying and lower-paying jobs.

The above is true for goods-producing industries, especially manufacturing, and true for service industries as well. And, if it is not already obvious from seeing restaurants, beauty salons and shopping malls shuttered during the first months of the pandemic, this is a service-industry recession. Ninety percent of the Salem workers unemployed in April and May were in service-related employment and only ten percent in goods-producing employment.

In stark contrast, in the so-called “Great Recession” of 2008, half the job losses in Salem were in goods-producing jobs and half in service industry jobs. This current downturn is truly unique.

Let’s examine wages in the parts of the service industry that lost the most jobs from March to April of this year.

The average wage for all industries in Salem in 2019 was $42,473 a year (total industry wages divided by total number of employees).

Annual wages in service industries experiencing most of the job losses were the following:

· $19,425, the annual wage in Leisure and Hospitality, including hotels, restaurants, movie theaters, casinos and other types of recreation and entertainment; this industry took 36 percent of all private sector job losses in Salem from March to April;

· $23,596, Social assistance, including home health care and child day care;

· $29,073, Other Services, including barbers, hairdressers, shoe repair, and auto lube shops;

· $30,692, retail trade; and

· $31,321, staffing agencies.

The shutdown has disproportionately affected workers in lower paid jobs.

Why is this a challenge to an economic recovery?

In spite of historically low unemployment rates, the economy wasn’t working well for everyone before the pandemic happened. This was especially so for workers on the low end of the pay scale, many of whom, in addition to earning low wages, had no health care or other benefits.

It is unknown at this point how many of the lost service industry jobs will come back, or when, for at least two reasons. We don’t know what the virus will do and what the public policy response will be, and we don’t know how much the experiences of the last few months will change the consumer spending patterns of Salem’s residents and whether the changes will be temporary or permanent.

Some of the unemployed are collecting comparatively generous unemployment benefits now. But the federal add-on of $600 a week will expire soon, and the rest, in a few months. If some service industry jobs disappear, these folks will need to look for other employment.

They will need a lot of help. Many of the unemployed do not have the education or skills to easily transition into another type of work. The Oregon Employment Department has been tallying the characteristics of recent unemployment claimants and found that 53 percent of them had only a high school diploma or less. Workforce programs that help educate and train the unemployed have been in existence in the U.S. and Salem since the early 1960s, but their funding has been steadily declining since the late ‘70s.

Additional unemployment insurance, health care support, and more funding for job training, at the very least, will likely be needed to help the mostly low-paid service industry workers who have taken the brunt of the pandemic-related shut-down. An economic recovery that benefits everyone may not be possible without doing all this and more.

Pamela Ferrara is a part-time research associate with the Willamette Workforce Partnership, the area’s local workforce board. Ferrara has worked in research at the Oregon Employment Department, earned a Master’s in Labor Economics, and speaks fluent Spanish.