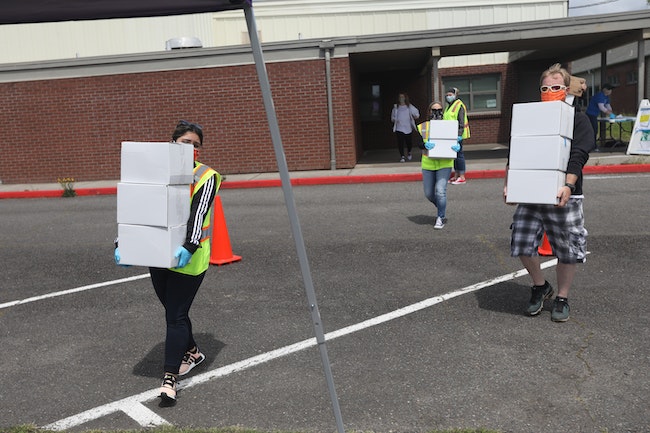

Farm to Families food boxes are distributed from the St. Vincent De Paul food bank on Friday, May 22 . (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

Farm to Families food boxes are distributed from the St. Vincent De Paul food bank on Friday, May 22 . (Amanda Loman/Salem Reporter)

Working-class families in Oregon were struggling to afford necessities before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, a trend advocates worry could fuel a homelessness crisis when a statewide moratorium on evictions expires at the end of the month.

A report released this week from United Way details the rise in Oregon families who earn too much money to be counted as “poor” under federal law, but who still struggle to pay for basics like rent and childcare and don’t have the savings to cover an unexpected expense.

“These are families that are basically one regular normal life crisis away from being more profoundly insecure,” said Elizabeth Schrader, chief development officer for United Way of the Mid-Willamette Valley, which participated in the statewide study.

The U.S. and Oregon have seen historically low unemployment rates in recent years, with high levels of economic growth since the end of the Great Recession in 2010. The state’s poverty rate has fallen slightly since, with about 12% of Marion County families considered in poverty in 2018. For a family of four, that meant earning less than $25,100 per year.

But the share of families earning enough to live comfortably also fell in the same period, the report says, largely because small increases in wages haven’t kept pace with growing costs for housing and health care.

In Marion County, 27% of households in 2010 earned more than the poverty limit, but not enough to cover essentials like rent, food, healthcare and groceries, about $40,000 per year.

By 2018, the cost of those basic items rose to about $60,000 per year for a family in Marion County. About 41,600 families, 35%, earned too much to be considered poor, but not enough to cover basic costs.

Black and Hispanic families were especially likely to struggle, the report found.

Schrader said the report shows a disconnect between official measures of economic health and the experiences of many blue-collar working families, who have seen years of rising rent without a corresponding increase in wages. While unemployment was at an all-time low before the pandemic, low-wage jobs also make up a far greater share of Oregon’s economy than they did before the Great Recession.

Schrader said blue-collar families took a large economic hit as businesses closed during the pandemic, with restaurant and accommodation workers out of a job and often waiting weeks or longer to get unemployment.

United Way began distributing free food boxes to families in need in April and planned to wrap up in June, but the need has been so great they’ve decided to continue through at least July, Schrader said.

State money for rent relief distributed through Mid-Willamette Valley Community Action Agency will help about 2,000 families pay rent despite lost wages. But Schrader said more will be needed to help working families recover and ensure Oregon isn’t hit with a wave of new homeless families over the summer.

“While we have this opportunity we need to secure this population,” she said.

SUPPORT SALEM REPORTER’S JOURNALISM – A monthly subscription starts at $5. Go HERE. Or contribute to keep our reporters and photographers on duty. Go HERE. Checks can be sent: Salem Reporter, 2925 River Rd S #280 Salem OR 97302. Your support matters.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.