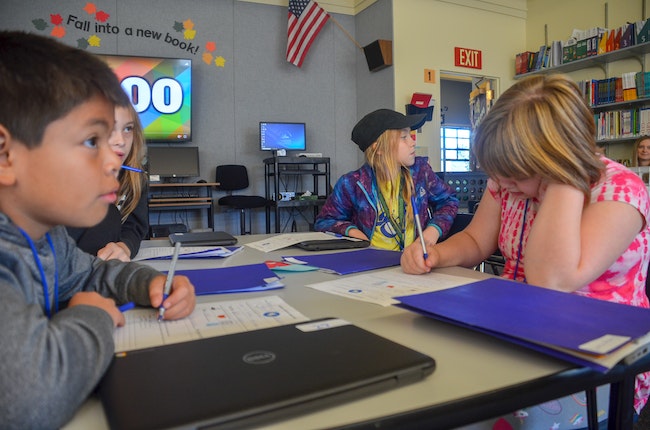

Jared Vergara Santana, left, Evelyn Francis, right, Iris Johnson, right back and Lillyana Green, back left, work on newspaper articles at Hoover Elementary School. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Jared Vergara Santana, left, Evelyn Francis, right, Iris Johnson, right back and Lillyana Green, back left, work on newspaper articles at Hoover Elementary School. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

In late May, about 10 teachers and classroom aides from Judson Middle School gathered online to plan for the end of the school year.

They talked about final projects, which for many students included a video presentation about an African country, and swapped ideas on how to recognize and say goodbye to students without doing so in person.

The discussion included bright spots for distance learning, the largely online schooling which began in mid-April, after Oregon’s students had been out of school for one month.

Danyelle Thomas, who teaches sixth and seventh grade language arts and social studies, said they’ve gotten to know more about students’ home lives through calls home and one-on-one help.

But teachers also reported struggling with sometimes low participation and said it’s been difficult learning how best to teach individual students in a completely new environment.

“Trying to figure out what works best has been such a challenge,” said Kim Daniels, who teaches seventh grade language arts and social studies.

The impacts of mass school closures related to the coronavirus will be the subject of education research for years to come, but early results suggest a grim forecast for kids, especially those who were already struggling before schools shut down.

Researchers at McKinsey & Company estimated low-income students could return to school a year behind where they would have been had schools not closed, assuming in-person classes resume in January 2021. An average student would be about seven months behind.

Black and Latino students will also lose more ground than white students, because they’re more likely to attend schools where the quality of remote instruction has been poor and less likely to be able to access classes, researchers found.

“In short, the hastily assembled online education currently available is likely to be both less effective, in general, than traditional schooling and to reach fewer students as well,” researchers wrote.

Oregon may suffer less because state officials required districts to offer some form of distance learning, while 28 states required no instruction after schools closed.

In the Salem-Keizer School District, administrators had embraced data as a tool for tracking both individual students’ learning and the needs of schools and the district as a whole.

Now, they’re largely blind to how students are doing.

By state mandate, schoolwork now is optional for students and ungraded. State standardized tests in the spring were canceled, and district tests used to measure elementary schoolers’ progress in reading and math weren’t done.

Administrators know educators have been in touch with about 96% of elementary school students at some point since schools closed in mid-March, assistant superintendent Kraig Sproles said. That still leaves about 700 kids with no contact with teachers at all.

The percentage for middle schools are similar, and about 100 high schoolers haven’t been in touch with their schools.

Sproles said Salem-Keizer doesn’t have demographic data about the kids it hasn’t reached, but he knows anecdotally the same kids who were struggling before schools closed. Homeless students or those with unstable home lives were especially unlikely to tune in, he said.

Despite large laptop distributions at every high school in the district, schools were still passing out Chromebooks in late May – seven weeks after the start of remote classes.

Teacher track “engagement” in online classes, a measure teachers said doesn’t capture whether students are actually learning.

“We have to count them as engaged if they breathe in Google Classroom, not if they do work,” Daniels said.

Other teachers described a similar pattern. The first two weeks of distance learning in April were hectic as students got Chromebooks, parents adjusted schedules and everybody figured out how classes would work.

“It was chaos,” said Lucia Sanchez, a parent of two Salem-Keizer students, speaking in Spanish.

Sanchez is a parent educator at the Salem-Keizer Coalition for Equality, which works with Latino parents. She and other coalition staff called about 500 families to assess needs and connected with about 300.

Many reported they didn’t know how to get online or use the computers the district had sent home. Some were caring for nieces and nephews while their parents worked or were managing schedules for four children at the same time.

“We realized that many families were dealing with depression, anxiety, panic, stress but said ‘I don’t have anyone to talk to,’” Sanchez said. Many were concerned about their kids falling behind in school.

Coalition workers suggested a daily schedule for parents of young children and talked through problems over the phone, delivering Chromebooks for families who couldn’t drive and printed packets of schoolwork for families who couldn’t get online. They also helped parents reach school counselors and principals for direct help.

Sanchez said she’s seen many parents become more confident working with their kids as the closure stretched on.

“We as parents are the first and most important teachers of our kids,” she said.

Educators said they’ve seen many parents make Herculean efforts to keep kids engaged in school.

Jessica Brenden, principal of Hallman Elementary School, said student engagement has been higher in the school’s Spanish-English bilingual classrooms than in English-only ones. The northeast Salem school has among the highest poverty rates in the district.

Daily, between 30% and 60% of Hallman’s students participated in school, she said. Over the course of a week, teachers report nearly every student was in class.

Some parents said the new format was a positive experience. Flora Galindo is the mother of three Hallman students in kindergarten, second and third grade. She was let go from her job in a children’s clothing store in Salem because of the pandemic, so she’s worked through classes with her kids.

Galindo said she’s learned more about how one son’s ADHD impacts his learning and thinks she’ll be better able to help him with school in the future. She’s also brushed up her own understanding of math.

“We were stuck on fractions for a good two days maybe,” she said. “We all taught ourselves and we all learned together as a single bunch.”

But Brenden and teachers said they’ve seen less engagement as the spring has worn on. Some parents have given up, exhausted by the demands of balancing schedules for multiple students.

At Judson, Thomas said her students’ engagement has dropped weekly. Daniels reported a dip in weeks three and four, followed by some improvement. By late May, about two-thirds of her students were regularly completing assignments, she said.

Brenden said she’s talked to parents who have stopped sending kids to classes entirely because they were burned out or overwhelmed.

Superintendent Christy Perry said she’s asked educators to prioritize relationships with students and is optimistic the connections built under challenging circumstances will lead to teachers to connect better with students once classes resume in the fall.

“Every kid’s going to be coming back with a gap of some sort,” she said.

Brenden said at Hallman, educators see kids who struggle with behavior in class shine in online classes, while some students who do well in regular school have trouble staying focused online.

She said those observations are leading teachers to discuss how they can better tailor school to serve everyone when classes resume.

“It’s given us a really great experiment to see what would happen if school weren’t mandatory,” she said. “What we’ve learned is that … we always want to have schools that kids want to be at, but we’ve got work to do to make sure that happens.”

SUPPORT SALEM REPORTER’S JOURNALISM – A monthly subscription starts at $5. Go HERE. Or contribute to keep our reporters and photographers on duty. Go HERE. Checks can be sent: Salem Reporter, 2925 River Rd S #280 Salem OR 97302. Your support matters.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.