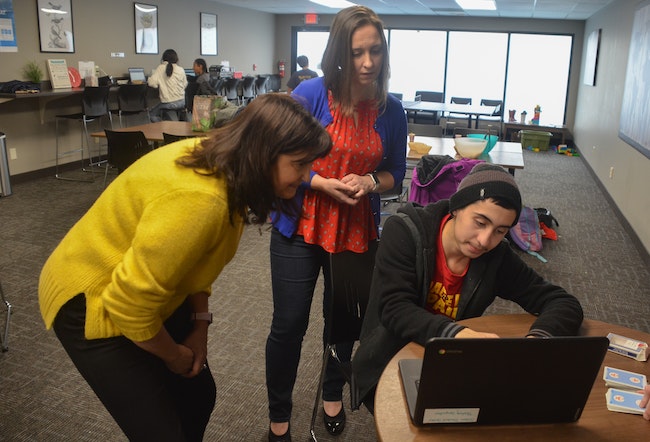

Micah Zavala logs in to his student account at the Baker Web Academy student center in Salem as his mother, Sara, and school support Suzy Kottek look on. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Micah Zavala logs in to his student account at the Baker Web Academy student center in Salem as his mother, Sara, and school support Suzy Kottek look on. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Schools serving thousands of Oregon students online won’t see any additional money to support them while Oregon embarks on a $2 billion education spending plan.

The state’s 19 virtual charter schools, which have about 13,000 students, were excluded from the largest pot of money in the Student Success Act, a new state law intended to improve schooling for students across Oregon.

Charter schools are publicly funded but privately managed schools that operate under a contract with a sponsoring school district. About one in three Oregon charter students attends an online school.

The exclusion of online charter students frustrates parents who say their students need the help the law is intended to provide, which can range from mental health counselors, more time in class, activities like art and music and more teachers to reduce class size.

Sara Zavala enrolled her son, Micah, at Baker Web Academy for sixth grade after he attended five elementary schools in the Salem area.

The family didn’t move but instead Micah was shuffled school to school because of the availability of special education programs and classrooms, she said.

He struggles with reading and wasn’t getting enough individual help to be successful in class, she said. And Zavala said even when she reached out to schools, she often wasn’t aware what her son was supposed to be working on or how he was doing in class.

After fifth grade, she began researching online schools and settled on Baker, where Micah has been for five years.

He gets bi-monthly home visits from a teacher who’s been with him since the beginning and can tailor his classes to meet his needs or build specific academic skills.

“She knows Micah. She knows year to year what he’s going through,” Zavala said. She has an online dashboard where she can see exactly what his assignments are and any areas where he’s struggling.

And though the school is virtual, students don’t always work at home. Baker has a center in Salem where kids go to do schoolwork and get help. This week, the school hosted a “fun day” where Micah joined classmates playing cards and eating popcorn.

“I don’t think we could have ended at a better place,” Zavala said.

Some charter school students in Oregon will benefit from the law. Twenty-six brick-and-mortar charters can apply for money from the Student Investment Account, the state fund being split among Oregon public schools. None of Salem-Keizer’s schools qualified.

To receive money, those schools had to have a certain percentage of students with disabilities, low-income students and students of color, all groups the law is intended to help. Charter schools in Oregon have more white students than the state average, according to Oregon Department of Education data.

Physical charter schools could also apply for funds through their sponsoring districts. But virtual charter schools were explicitly excluded, even if their demographics were similar.

Aaron Fiedler, spokesman for the House Majority Office, said legislators were focused on “making sure that whatever new revenue we had for school was going into public schools.”

“A billion dollars is a lot of money but spread out over 200 school districts, only goes so far,” he said. Legislators also had concerns about virtual charters because, while they’re non-profit organizations in Oregon, many operate under contracts with commercial companies that sell curriculum and online learning platforms, he said.

Parents said they were disappointed to learn their school had been excluded since it’s also taxpayer funded.

“This is also a public school. It’s just designed differently than a brick-and mortar -school,” said Stacy Vrooman, a parent with two sons at Baker. She previously homeschooled her students before enrolling them online.

Baker Web Academy is sponsored by the Baker School District in eastern Oregon, and its demographics are about the same as that district. Eight in 10 students are white, about half are low-income, and 13% have a disability – about the same rate as Oregon. Had it qualified, the academy would have received about $1 million.

Daniel Huld, the school superintendent, said virtual charter schools weren’t aware of the wording of the law until it was too late to do anything.

“By the time we caught that late in the session there really wasn’t a lot we could do,” Huld said.

Virtual schools could still receive some money from the law under statewide programs intended to improve high school graduation, but it’s a fraction of what’s available from the Student Investment Account.

If Baker had received funding, he would have used the money to hire mental health counselors. He said the school regularly sees students looking online for information about topics like self-harm and trying to better understand their world.

The school’s existing counselors can help students who have immediate crises, but they don’t have time for other counseling.

“A lot of our students have mental health social emotional needs and they won’t have access to additional counselors like other schools,” he said.

Baker also explored adding summer programs for students who are behind in elementary school, he said, but scrapped the plan after they learned they wouldn’t receive money.

“It’s a huge loss for us and for our students,” he said.

Correction: Baker students receive home visits bimonthly, not biweekly.

Contact reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.