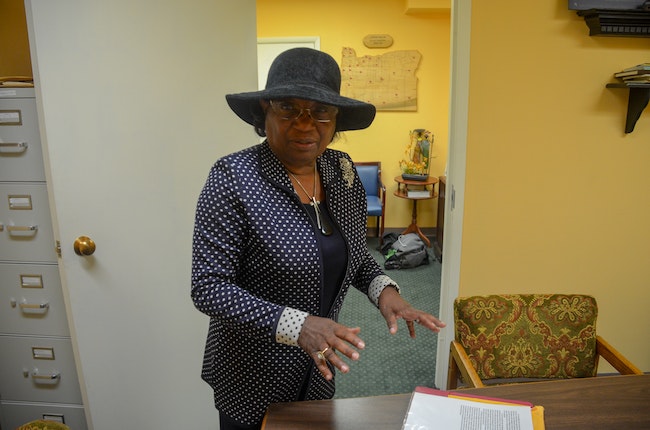

Willie Richardson, president of the Oregon Black Pioneers, speaks about the group’s research at their Salem office. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

Willie Richardson, president of the Oregon Black Pioneers, speaks about the group’s research at their Salem office. (Rachel Alexander/Salem Reporter)

When Gwen Carr moved to Oregon from southern California in the 1980s, she got some skepticism from her black friends.

“They said, ‘You’ll be back because there aren’t any black people in Oregon, there have never been any black people in Oregon,” she recalled.

Carr’s work over the past 15 years has proven them wrong.

She’s the secretary of Oregon Black Pioneers, an all-volunteer group researching, documenting and sharing the history of black Oregonians across the state.

“History is important and if you don’t know and understand it, particularly your very own, you can be at a loss,” said Willie Richardson, the organization’s president.

[ Help build Salem Reporter and local news – SUBSCRIBE ]

Carr and Richardson live in Salem and work with board members and volunteers across Oregon to create exhibits, present in local schools and educate the public about the long legacy of black Oregonians and the state’s history of slavery, racist laws, civil rights protests and more.

Both women are retired, and neither is trained in history. Richardson owned a dress shop in Salem, and Carr worked for years at the SAIF Corporation.

Their hope is to show the role black people played in Oregon’s development, “to tell it accurately and honestly,” Richardson said.

The Black Pioneers recently won a nearly $22,000 grant from the Oregon Cultural Trust to help hire a part-time director to carry on the work. The Trust is a state organization funded through voluntary contributions by taxpayers.

Richardson got involved in the group shortly after its beginnings in 1993, when educator Carol Davis moved from Seattle to Salem to take a job as a deputy superintendent.

“She recognized immediately that there was very little African-American history being shared” in local schools, Richardson said.

Davis modeled the group after the Northwest Black Pioneers in Seattle, working with Sen. Jackie Winters and other community leaders to research and document the lives of black Oregonians.

Their early work focused on school presentations, especially for Black History Month in February. After a few years of work, the group became mostly inactive until Richardson decided to resurrect it in 2004.

She began thinking about how they could best tell the story of black Oregonians.

A postcard advertising an Oregon Black Pioneers exhibit focused on the 1940s to 1960s at the Oregon Historical Society (Courtesy/Oregon Black Pioneers)

A postcard advertising an Oregon Black Pioneers exhibit focused on the 1940s to 1960s at the Oregon Historical Society (Courtesy/Oregon Black Pioneers)

Oregon’s black population has always been small: about 2% of Oregonians, or just over 80,000 people, self-identified as black on last year’s Census Bureau survey. Eight in ten live in the Portland metro area.

But Richardson said the group has been able to identify a historical black presence in all but two Oregon counties, using Census records, family Bibles, obituaries, local cemeteries and more to gather information.

Including that history doesn’t mean segregating the black story into a single plaque in a larger history exhibit that explains what black people were doing during a given time period, she said.

It’s about interweaving the experiences of all people in Oregon into a more accurate picture of the past, one that includes the black slaves who traveled with their white owners along the Oregon Trail, and the free black people who became business owners in the early days of Oregon Territory.

“When you’re telling the Oregon story it should be inclusive,” she said. “You can’t tell the story of Oregon without talking about Native Americans. You can’t tell the history of Oregon without talking about African-Americans … all those groups were part of the story from the very beginning.”

The black presence in what is now Oregon stretches back to the first non-indigenous people to venture to the Pacific Northwest. An African man named Marcus Lopius was aboard the Lady Washington, which landed in Tillamook in 1788, and William Clark’s slave, York, was part of the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Uniforms on display in an Oregon Black Pioneers exhibit about railroad workers at the Oregon Historical Society in 2013. (Courtesy/Oregon Black Pioneers)

Uniforms on display in an Oregon Black Pioneers exhibit about railroad workers at the Oregon Historical Society in 2013. (Courtesy/Oregon Black Pioneers)

Richardson and Carr said there’s a common misconception that slavery never existed in Oregon. Oregon was a free state, as decided by white voters when they approved the state’s constitution in 1857, but that’s not the full story.

The Oregon Black Pioneers documented the decision-making leading up to that vote in their book “Perseverance,” a history of African-Americans in Marion and Polk counties, published in 2011.

Those campaigning for Oregon to be a free state included Salem businessman and newspaper publisher Asahel Bush, for whom Bush’s Pasture Park is named.

Bush’s motivations weren’t altruistic: he believed blacks were destined to be subordinate to whites, but thought slavery was impractical given Oregon’s climate and population. (Richardson takes pleasure in knowing Bush was a founder of Pioneer Trust Bank, which now donates an office in its building to Oregon Black Pioneers.)

Bush supported banning free black settlement in the state and Oregon voters agreed. In 1859, Oregon was admitted to the union as a free state where, on paper, black people were not allowed to live.

But on the ground, the history was more complicated. Carr said many settlers came to Oregon from slave states with their slaves in tow. Some set them free on arrival in Oregon. Many did not.

When people think of American slavery, they tend to picture large plantations, she said. That’s made it easier to overlook Oregon’s history of slavery.

“Slavery in Oregon didn’t look like that. It looked like poor whites that had one or two slaves that they brought along with them,” Carr said.

Black Salem residents paid property taxes but could not attend school with their white peers. Little Central School opened in 1867 in Salem after the black community raised $430 to open it. (Courtesy/Oregon State Library)

Black Salem residents paid property taxes but could not attend school with their white peers. Little Central School opened in 1867 in Salem after the black community raised $430 to open it. (Courtesy/Oregon State Library)

Laws against black settlement were unevenly enforced, and historical records show some cases where white neighbors testified on behalf of black citizens who local authorities tried to remove, and others where whites ran African-Americans out of town.

But through it all, black people remained in Oregon – as landowners, business owners, laborers and more.

Richardson wants to highlight those successes and contributions, and not shy away from the uglier aspects of Oregon history, including the strong Ku Klux Klan presence and the history of racist laws.

“That’s what’s wrong with history now – we’ve left too much out,” Richardson said. She believes understanding that history is key to not repeating it.

Over the years, Oregon Black Pioneers have put together exhibits with the Oregon Historical Society and other groups, showcasing their research. The group’s exhibit about the civil rights movement in Eugene opens this week at the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

The visibility their work has brought to African-American history is one reason they were selected for the Cultural Trust grant, said Brian Rodgers, the trust’s executive director.

“That kind of sensitivity and knowledge and awareness of how to put together an exhibit that tells the story in a real way is extremely important,” Rodgers said.

The grant is part of a larger plan for the group to hand the reins over to paid staff and ensure the Black Pioneers have a sustainable future beyond a handful of dedicated board members willing to spend hours every week doing research.

They’ve collected file cabinets full of research on individual black Oregonians and are exploring ways to digitize that information and make it searchable, Richardson said.

And they’re always looking for more information.

Richardson said their goal isn’t to shame people for the past. Often, their research begins with white people who get in touch because they discover the name of a black neighbor, slave or community member in a family Bible or diary from their grandparents.

The group wants to preserve those snippets of history.

“It’s not about trying to make you feel bad because someone in your family … had a slave,” Richardson said. “It’s about identifying who that person was, and they become human. I am grateful that they stayed here. I am honored to tell this story.”

Reporter Rachel Alexander: [email protected] or 503-575-1241.

Rachel Alexander is Salem Reporter’s managing editor. She joined Salem Reporter when it was founded in 2018 and covers city news, education, nonprofits and a little bit of everything else. She’s been a journalist in Oregon and Washington for a decade. Outside of work, she’s a skater and board member with Salem’s Cherry City Roller Derby and can often be found with her nose buried in a book.