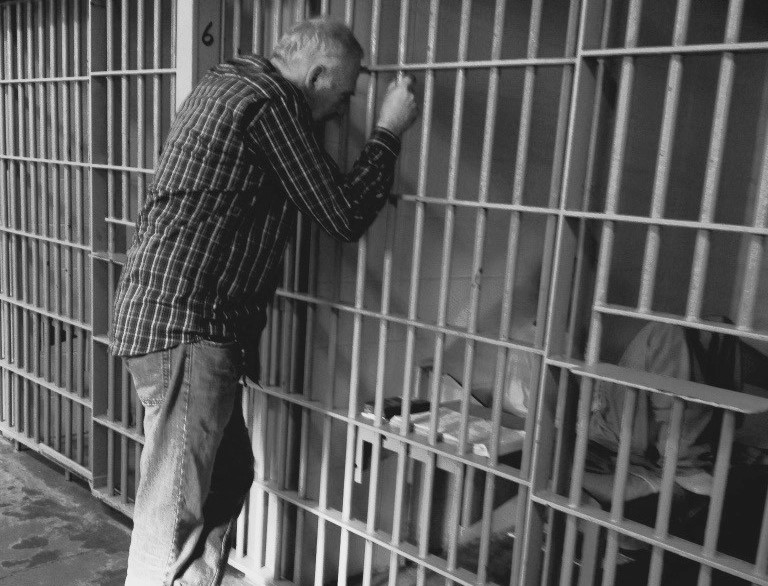

Former Judge Tom Kohl talking with a prisoner at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in 2014. (Photo courtesy of Tom Kohl)

As Tom Kohl was leaving, the prison warden called him back to sit and pray.

“Dear lord, don’t let these men rest until there is a Bible college in the Oregon Department of Corrections, amen,” said the warden, Burl Cain.

Kohl, 71, is about to answer that prayer. He has forged plans to provide the first four-year college program within the walls of an Oregon prison.

Kohl was inspired by what he saw in Louisiana.

Cain had instituted a program of what he calls “moral transformation,” bringing prisoners to the light of God . Part of that is a partnership with New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary to provide inmates access to a faith-based four-year college.

Working through a nonprofit, the now-retired judge is putting professors from Salem’s Corban University inside the Oregon State Correctional Institution. Starting next September, 25 prisoners will start their work on a four-year psychology degree.

“I think it was just the opportunity to transform the lives to help rehabilitate the inmates and getting them ready to transition back into the communities,” Jeremy Yraguen, the Correction Department’s education and training administrator, said of the partnership.

While this will be the first partnership with a four-year university, six community colleges partner with the agency to provide adult development assistance to prisoners getting their GED. Chemeketa and Blue Mountain community colleges provide access to college classes, which has been utilized by 421 prisoners since 2015.

Yraguen said agency officials considered the Christian-based nature of the schooling, but decided to continue because the college-in-a-prison would be open to all inmates regardless of faith.

Cain, now retired from the Louisiana prison, said in an interview that his program wasn’t controversial because it’s privately funded and open to all faiths.

“I didn’t have any push back, and I kept the separation of church and state,” he said.

Mike Patterson, provost of Corban, said the college has been interested in the goings on of the nearby prison, and was enthused to form the partnership.

Kohl said the nonprofit he started last year, Paid In Full, will fund the program, including paying for professors and transforming a 2,700-square-foot part of OSCI into a school. Kohl said he needs about $500,000 to get the prison school running. He’s planning to hold fundraisers and get some material, like computers and tablets, donated. The state will provide desks, chairs and corrections officers for security.

Like Cain, Kohl plans to “morally transform” criminals through the light of God.

“Generally, the easiest way to transform someone is through religion,” he said.

Cain said he’s seen that transformation first-hand. While he left the prison in 2016, he remains active in lobbying for Bible colleges in prisons. He said 15 states now operate them. He hopes to get that number to 40.

“When I first went there it was a very violent prison with over 4,000 lifers,” Cain said. “Our job in prisons is to correct deviant behavior.”

Inmates in any Oregon men’s prisons can apply but have to meet certain qualifications, and those accepted would be transferred to the Salem prison.

To be considered, inmates must have at least eight years left on their sentence, and lifers are more coveted by Kohl. That way, they have time to spread their knowledge and be a mentor to others in the prison system.

They must also have a high school diploma or GED and a clean disciplinary record for the past year. This will help ensure they will be respectful students and stay in the program, Kohl said. It also shows they are serious about rehabilitation. Prison staff can also recommend someone for admission.

Kohl said graduates will return to prisons around the state, serving as mentors, changing the culture from the inside. They’ll be better prepared for life on the outside, he said.

“Imagine someone is going back into North Portland after being released from prison,” Kohl said. “Instead of going back to North Portland with a .45 handgun in their hand, or a 9-mm handgun, they go back into their neighborhood with a college degree in their hand.”

The curriculum as planned will include 30 credit hours devoted to psychology and 30 to Bible studies. The remainder will be general education.

“It’s definitely going to have a strong ministry component, but it’s also going to have a strong psychology and sociology component,” Patterson said.

Patterson said since word got out about the program, he’s been approached by professors interested in teaching at the prison.

In Louisiana, Clifford Jones knows first-hand how such college courses can help. He was serving a 50-year sentence in Angola for his role in an armed robbery.

He said while incarcerated he had an encounter with God, and shortly after started preaching on the prison yard. He entered the program and was in the first graduating class.

“What’s critical is the relationships you build between inmates and security,” Jones said. “It changes the atmosphere within the penitentiary. It stopped riots. I watched Angola change from the bloodiest penitentiary in America to one of the safest because of the Bible college, and the men that get self-esteem and self-worth, and spread it through the population.”

Jones eventually won his release is now a pastor. He’s an example of what the Corrections Department hopes to achieve.

“Obviously a four-year degree increases their chance of being successful and not coming back, so this is a great opportunity,” said Jennifer Black, agency spokeswoman.

There is some anecdotal evidence to back this up. In 2012, Baylor University published a study looking at the impact of Bible colleges in prisons. It found inmates who participate in faith-based higher education are “significantly less likely to return to prison than comparable inmates who did not participate in such a program.” Baylor is a Christian college.

But for Cain, the validity of such programs doesn’t depend on sweeping change.

“If you have just one person who didn’t have a gun to their head, or get murdered or killed, it’s worth it,” he said.

For Kohl and Jones, the goal isn’t just to drop recidivism rates. It’s to impact lives through association, both in and out of prison.

“It took me to the level of being able to counsel, being able to teach, being able to preach, being able to make a living and actually help change lives, and actually give back,” Jones said.

Jones said the religious underpinnings of the program are important.

“I believe in moral transformation,” Jones said. “If they become morally transformed, when they come out it shows in their decision-making, it shows in giving love to family. It keeps them able of being productive citizens in society.”

Have a tip? Reporter Aubrey Wieber can be reached at [email protected] or 503-375-1251.